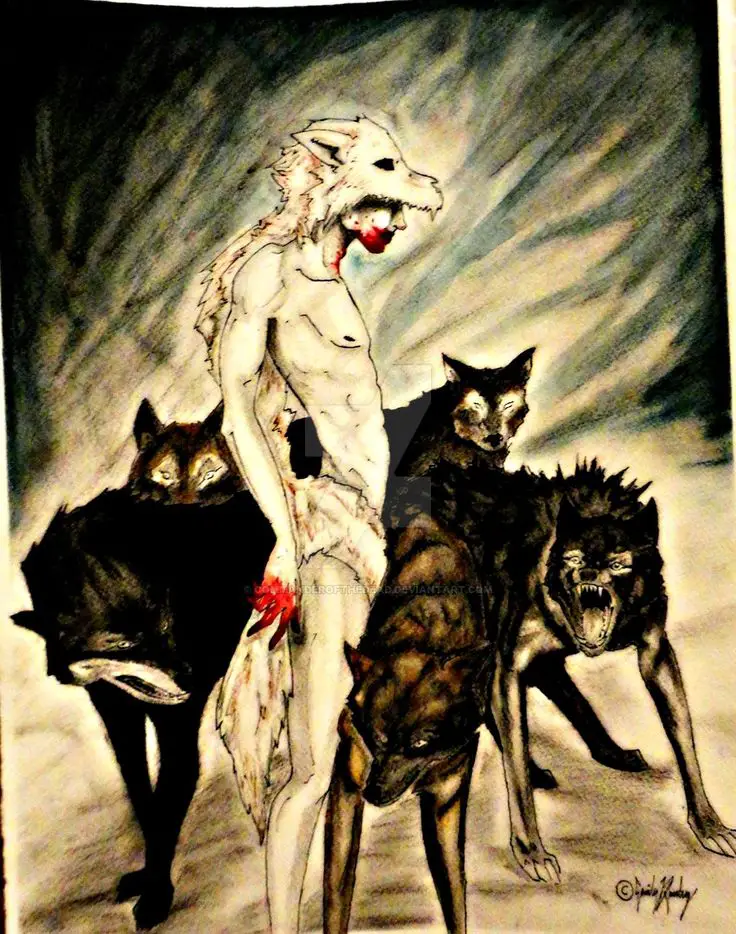

skinwalker, “He who walks in the skin,” is an English word that loosely translates the Navajo term Yenaldooshi o Naglooshi, which literally means "with it, walk on all four". Both of these definitions refer to a particular type of "shapeshifter" in Navajo folklore, a sorcerer able to assume the forms of different animals by wearing their skin. The Skinwalkers they can transform into wolf, deer, crow, owl or even into fireballs darting in the sky, but the most recurrent metamorphosis associated with them is that of coyote. The result is a monstrous hybrid that roams the wastelands of the southwestern United States at night, bringing pain and torment to humans. The Skinwalkers they can move at great speed, so much so as to equal a speeding car, but their movements are never completely natural: the footprints they leave on the ground are uncoordinated, and there are those who say they have seen them run backwards, with limbs twisted into impossible positions.

According to Navajo tradition, if you met one skinwalker, the most important thing would be not to look him in the eye: if this happens, he will have to kill you by blowing on your face a lethal dust made from the bones of corpses. You could try to shoot him: if wounded or killed, the shapeshifter will take on his human form again. Or, if you knew the native sacred songs or had amulets, you could try to keep it at a distance: Yenaldooshiin fact, they hate everything that is sacred and it is said that they cannot resist the temptation to profane sacred images, destroying them or sprinkling them with their urine.

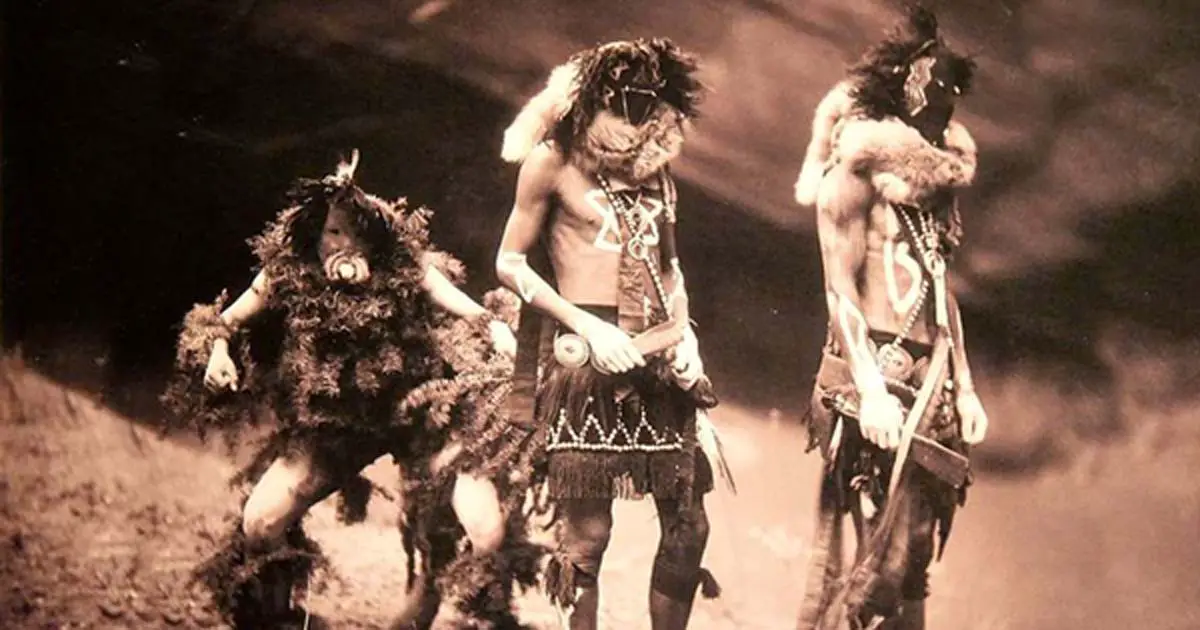

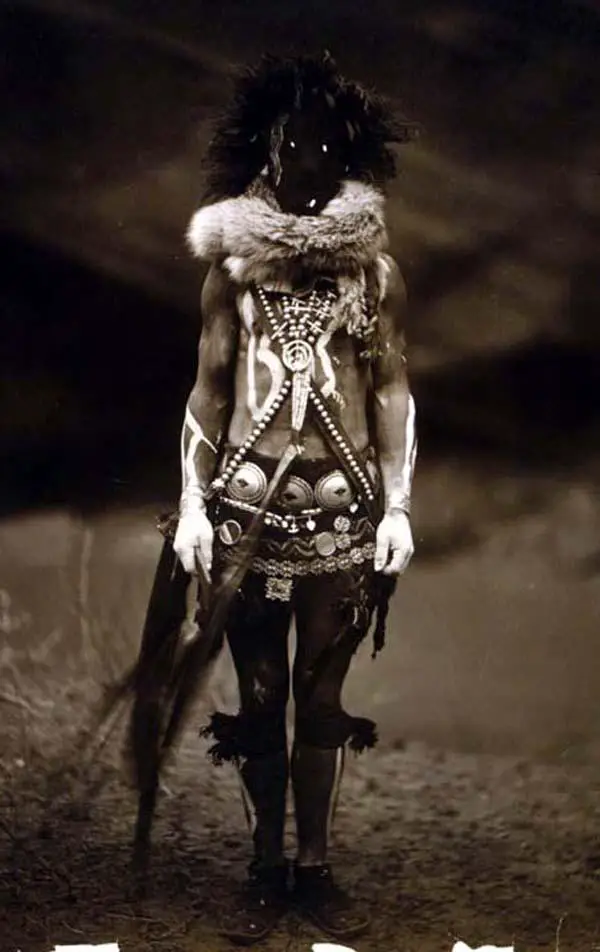

Faithful to the beliefs of the Navajo, during the day these mysterious beings hide in the darkness of the caves, on whose walls hang the skins they use to transform themselves. In their lairs, they sit naked, their faces covered with masks, among baskets full of human flesh, observed only by the empty dark circles of the skulls of their victims. On the ground, they depict their victims with drawings of sand, on which they later throw magic beans, to inoculate disease and suffering. But it is especially during the night that the Skinwalkers prowl and carry out their revolting deeds, which include cannibalism, hacking into graves to make their own dust, kidnapping children and babies, mutilating livestock, murdering innocent victims or those who, even if just inadvertently , they offended them.

Their arrival is usually heralded by a strong smell of coyote urine. When they approach, the dogs bark furiously and an impalpable dust descends from the ceilings, an omen of the deadly one they are about to shed. In some cases, they attack isolated hunters and throw the skin covering them at them, paralyzing them. Once the victim has been neutralized, the shapeshifter takes on his features, returning home in his place: his wife and family will find themselves in front of a different man, more taciturn and absent, but they will not suspect anything, until, with the passage of time, they will begin to feel a pungent feral smell.

According to Diné folklore — the way the Navajos call themselves, which means "The People" - the Yenaldooshi they are actually men or, in some cases, elderly and sterile women, who have joined an obscure initiatory brotherhood devoted to evil. The Skinwalkers follow the so-called "witchery way”, Which consists in the use of supernatural and magical powers for material and evil ends. It is said that in order to become part of this congregation, it is necessary to kill one of one's loved ones or loved ones. The motive for such a radical choice, in general, is resentment and the desire for revenge towards an individual or the entire community, but also a great greed for riches or the lust for power.

Lo skinwalker he embodies the antithesis of the Navajo worldview and his every action is a deliberate subversion of the values shared by the community. The spirituality of this people, in fact, is centered on the concept of hozho, a harmony that must reign both in the natural world and within the community and individuals, while the Skinwalkers are priests of chaos and discord, seeking to undermine this universal balance at every level [cf. The oral tradition of the "Big Stories" as the foundation of the Native Peoples Law of Canada].

The ways in which this opposition is expressed are many: while the culture of the Diné values the family, the shapeshifter despises parental ties, to the point of killing his own relatives; while the natives place the sharing of goods and brotherhood at the center, The Skinwalkers they are selfish and greedy for wealth; while death is a taboo to the Navajo, a topic that is carefully avoided, the Yenaldooshiinstead, they haunt cemeteries and handle corpses; while men live by day, shape-shifters prefer night. And so on: the same discourse applies to the practice of cannibalism and incest, which are also evident cultural taboos openly broken.

The reversal of values is so evident that it cannot be accidental. One key to understanding this radical antithesis is the transformation into a coyote. Coyote (Ma'ii in Navajo), in fact, is an important deity, present in the myths of the Navajo creation along with two other figures, the First Man and the First Woman and was precisely Ma'ii to teach humanity the dark secrets of witchcraft. Coyote is what anthropologists call a trickster, or a divine trickster: he is greedy and meddlesome and, with his rascals, gives rise to death and messes up the arrangement of the stars in the sky. The stories and songs about him are at times comic, but they also have a dark, violent and macabre aspect.

However, it would be simplistic to reduce the god Coyote to a purely evil being, because of his misdeeds they also have an extremely vital function, that of testing the possibilities of the universe, of taking human knowledge to the extreme limit because, without imbalance, equilibrium could not exist. Coyote's destructive acts, in reality, only reaffirm the universal order, and his stories serve not only to amuse but also to educate about what is right and wrong to do. The Coyote is, therefore, beyond the rigid Western polarity between good and evil, in a more natural representation of life, which welcomes opposites as necessary to constitute the whole. The devil and sin belong to whites, for the natives the universe is much more nuanced [cf. The Sacred Circle of the Cosmos in the holistic-biocentric vision of Native Americans].

It seems that the ambiguity of this divine figure is to be connected with the historical evolution of the Navajo people and neighboring ones, such as the Zuni, the Hopi and the Pueblos: in a first phase, in fact, these populations were based on hunting and gathering. of fruits and wolves and coyotes represented protective spirits. With the transition to breeding and agriculture, however, the former hunting companion became an enemy and a threat to the flocks to be fought at all costs. These two phases, chronologically successive, are instead contemporary and co-present in mythology, thus determining the ambiguity of the god Coyote, "good and bad" at the same time.

Beyond these considerations, there is no doubt that the Yenaldooshi embody precisely the most negative aspects of the God Coyote. Not surprisingly, in the Navajo language, calling someone by that name is the worst of insults. The word Ma'ii, also, not indicates only the coyote, but the entire family of canids, including wolves, dogs and foxes: this explains the variety of transformations of Yenaldooshi, which are also described as wolves or dogs.

Witchcraft in the American Southwest

When we talk about witches in the New World, in general, we refer to the persecutions of Salem, in the Northeast of the United States, where, at the end of the 1600s, more than 200 women were burned at the stake. Even in the Southwest, however, witchcraft was a terribly serious topic and even the natives, in the 1800s, had their own witch hunts.

In the lands cut by the Rio Grande, a particular cultural melting pot was created, which merged aboriginal beliefs with European superstitions, brought by the Spanish colonizers. The result was that, in the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, those places were crowded with witches capable of flying, of changing shape, of making potent love potions and deadly poisons. The chronicles of the Inquisition tell us of moonlit nights during which, among the mesquite bushes, disturbing ceremonies were celebrated, whose participants went wild in orgiastic dances, worshiping goats and kissing mysterious snakes. If Salem's witchcraft was the result of Christian superstitions and anxieties, that of the Northwest had a more syncretic character and blended Aztec reminiscences with native and Spanish folklore.

In 1848, at the end of the Mexican Wars, the Americans took over from the Spaniards, adding further elements to the already rich local folklore. While in old Europe the witch world was regarded as a predominantly female sphere, in the New World, on the other hand, no gender distinctions were made and witchcraft interested both men and women.

Compared to other local populations, the Diné were initially quite refractory to the Christian religion, in part because their horror of death did not favor the acceptance of a God who died on the cross and then resurrected. The belief in witchcraft, however, was deeply ingrained, and the Yenaldooshi they are but one of the many types of witches that haunted the collective imagination of this tribe.

They thought that sorcerers hid among the common people, poisoning food to spread disease, stealing to get rich, and ruining livestock and crops for revenge. Such a conviction led to suspicious and circumspect behavior not only towards whites, but also towards members of the same tribe: a sudden wealth, but also an offer of food by strangers could denounce the presence of a sorcerer.

In 1864, the entire universe of the Diné collapsed. To allow the whites to colonize their lands, General James Henry Carleton decided to deport them from Arizona to New Mexico, in the Bosque Redondo reservation. The deportation, which went down in history as "The long march of the Navajo", took place several times: thousands of Indians, with the elderly, women and children, were forced to walk more than 700 km, a deadly journey that cost hundreds of human lives. The Navajos, especially the elderly, women and children, died of cold, fatigue and hunger. In the story, a much less jovial Kit Carson played a prominent role than the one we are used to meeting every month in the pages of Tex, who broke the resistance of the natives by destroying their crops and exterminating them.

The deportation ended in 1868, when, following the signing of a treaty, the Navajo were repatriated to their homelands, but the impact on society was devastating, not only for the losses suffered, but also for the fact that their entire cultural and traditional horizon had been obliterated and disrupted by the whites. In total chaos, abandoned by their gods, the Navajo tried to restore order, identifying the culprit in the very beings they feared most: the sorcerers, who have always been enemies of their people. Mutual accusations of witchcraft multiplied dramatically, in a climax that culminated in the Navajo Whitch Purge of 1878, the "Purge of the Sorcerers".

It is said that members of the tribe found a bundle inside the belly of a corpse. They were bewitched fetishes and cactus thorns, the food of the witches, wrapped between the pages of the Treaty signed in 1868. It was the necessary proof to start the autodafé, which cost the lives of 40 presumed skinwalkers, before being discontinued by the United States Army.

It is certainly easy to condemn an episode like this, dismissing it as a mere primitive and naive superstition, in which a group of people, probably completely innocent, was used as a scapegoat on which to vent the anger of deportation. One wonders why the Navajos didn't take it out on whites directly, rather than turning violence internally.

In reality, the “scapegoat” mechanism is much more refined and complex and operates, in a more or less latent way, in all societies. The French philosopher and anthropologist René Girard has dedicated his entire life to highlighting its characteristics. According to his analysis, in all societies, both primitive and more advanced, there is a substratum of violence which, if not channeled, would lead to the self-destruction of the communities themselves.

The scapegoat serves precisely this purpose: to channel violence towards a victim, to prevent it from spreading devastatingly. "Always and everywhere," says Girard, "when human beings either cannot or do not dare to vent their anger on the things that have unleashed it, they unconsciously seek substitutes, and the less they can find them." It is not so important that the sacrificial victim is actually the culprit of the misfortune, but rather that he is identified as such. It is precisely the process of identification, accusation and purification, in fact, that contributes to the rebuilding of the social order and the re-establishment of harmony.

In the specific case, it didn't matter that the accused were actually able to transform into coyotes and spread death. The solution of the evil does not lie in the elimination of the true culprit but rather in the process that leads to identifying him. To identify a culprit, in fact, it is first of all necessary to establish a consensus on who to persecute and, to do this, it is necessary to consult, dialogue, confront each other. In this way, the sacrifice of a victim, even if innocent, leads to the re-establishment of the lost order: social harmony is rediscovered through a controlled exercise of violence. All of Girard's work focuses on the description of this mechanism, which he defined as "mimetic-victim", which does not concern only the tribes of the so-called primitive peoples, but every type of society, including ours. The mechanism of substitution, which may appear naive on superficial examination, works all the better the more unconscious it is, and the case of the Navajos is a prime example of this.

The archetype of the shapeshifter in mythology

Again, the history of Skinwalkers provides a useful example and food for thought. The archetype of the shapeshifter, in fact, has been declined in many versions, different for their geographical and temporal location. A first and immediate parallel can be drawn with the werewolves of the European tradition: both, in fact, undergo a feral transformation that leads them to anthropophagy. However, the two shape-shifters are different for the modalities of the mutation: while for the werewolves it occurs in an uncontrollable way, triggered by the full moon, for the Skinwalkers it is instead the fruit of a conscious decision. Similarly, while lycanthropy is often the consequence of a witch's curse, in the case of Yenaldooshi the process is reversed: it is the sorcerer himself who chooses the bestial transformation in order to expand his possibilities of doing evil [cf. Metamorphosis and ritual battles in the myth and folklore of the Eurasian populations].

This voluntariness of transformation brings to mind another fascinating chapter of Scandinavian mythology: i Berserker. These mythical Nordic warriors dressed in bear or wolf skins and, before the battle, were able to be pervaded by an unstoppable fury, in a trance which made them ferocious and lethal warriors, insensitive to wounds. The wrath of the Berserker it is a theme that has found various explanations. It seems, in fact, that the trance hypnotic could be induced through the intake of psychotropic substances, hallucinogenic mushrooms or cereals attacked by a particular parasite, as in the case of ergot. On the other hand, there are those who argue that this mental state was caused by medical pathologies, such as porphyria or Paget's syndrome.

This sort of bestial invasion was present in many European cultures: even the Romans, for example, had celebrations called Lupercals, whose officiants, the Luperci, wandered around the city half naked, their hips surrounded by a bloody skin, torn from the sheep that had just been sacrificed. During this feast, which took place in February, men sprinkled blood and scourged women, in a sort of collective fertility rite [cf. Lupercalia: the cathartic celebrations of Februa]. As for the Roman world, it is interesting to note that the way of defining the werewolf closely resembles that of the Skinwalkers: versipellis, "The girapelle". The name derives from the belief that werewolves had hair that grew inwards and that only during the mutation did they put it on display, turning it outwards.

Another fertile ground for comparison, as we have already seen, is that with European witchcraft: although originating from very different belief systems, such as Christianity and native spirituality, the two figures are certainly similar, although different and specific. , and this contiguity is the result of the contact between the two cultures.

Also in Indian folklore there is a figure who remembers him skinwalker: Wendigo. Although this monstrous and bestial being is typical of the Algonquian stock, located in the north of the United States and Canada, Wendigo e skinwalker they share their anti-social nature. The transformation, in both cases, is caused by an exasperated greed and selfishness, which contradict the community sharing that underlies the way of conceiving the world of the natives [cf. Psychosis in the shamanic vision of the Algonquians: The Windigo e Jack Fiddler, Wendigo's last hunter].

On the trail of the Skinwalker ...

Literature:

- Tony Hillerman, Skinwalkers, Harper, 1963

Non-fiction:

- Guy H. Cooper, Coyotes in Navajo religion and cosmology, in The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, VII, 2, 1987

- Jean Van Deliner, Wayward Indians: the social construction of the Native American Indians, Oklahoma State University

- Rene Girard, Violence and the sacred, Adelphi, 1992

- Colm A. Kelleher and George Knapp, Hunt for the Skinwalkers, 2005

Noah Nez, Skinwalkers, in Skeptical Briefs vol. 22.1, 2012 - Marc Simmons, Withcraft in the Southwest. Spanish and Indian supernaturalism on the Rio Grande, 1974

Film:

- James Isaac, Skinwalkers - The note of the red moon, 2006

- Devin McGinn, skinwalker ranch, 2013.

- Jan Egleson, Coyote waits, 2003

Music:

- Robbie Robertson and the Red Road Ensemble skinwalkers, in Music for Native Americans, 1994.

A comment on "Yenaldooshi, the shape-shifting "Skinwalker" of Navajo folklore"