Let's retrace the last saga of the Icelanders, composed in the fifteenth century and recently returned to us by Hyperborea.

di Claudia Stanghellini

There is an island, in the north of Europe, which fascinates the contemporary imagination with geothermal pools, ancient glaciers and the dream of unspoiled nature. A place where the presence of the human being has managed to integrate in harmonious symbiosis with the surrounding environment and its difficult beauty, the harshness of the climate, the hostility of the soil. A land that has become the home of a people who have tied its traditions, its language, its stories to it. We are talking aboutIceland, whose colonization dates back to the XNUMXth century. A.D

Between 870 and about 875, Norway is unified under the scepter of King Harald who centralized all the landed property in his own hands and then redistributed it, according to feudal logic, to the warriors who had fought alongside him. Society is thus reorganized according to a hierarchical criterion and the ancients jarlar e hersar, once first peers compared to free farmers, they are transformed into state officials directly dependent on the sovereign authority. The administrative and political centralization is followed by religious centralization, with the suppression of that cultic pluralism which constituted the most singular trait of late Nordic paganism. Hladir, in the Trondheim area, will in fact become the heart of the national religion and later, under the reign of Olaf, son of Tryggvi, one of the most active centers for the spread of Christianity in Norway.

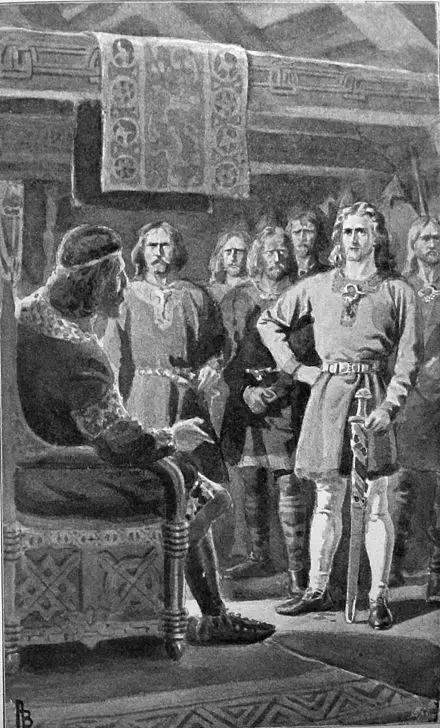

The new political configuration generates opposition not only from the local potentates, but also from the agricultural population. However, the rebel factions are severely defeated in the battle of Hafrsfjörd [1]. At this point, the only viable alternative for Harald's opponents to power is voluntary exile. Many choose Iceland, at the time an uninhabited island discovered only a few years earlier, which would have given way to start from scratch to those who had wished. [2]:

They thus intended to save that archaic ideal heritage, which still maintained, almost unchanged, the most sincere values, which had nourished Nordic and Germanic society, by transferring it - as far as possible - to a new location and destining it to a new life..

The historical and literary testimony that we still have today of this material and spiritual transmigration from Norway to Iceland and of the rebirth of an archaic world that did not want to perish is the saga.

The term "saga”, In Icelandic, means“ history ”. However, in the specialist it assumes greater semantic precision and is generally used in reference to prose texts (or possibly prosimeters) composed in the medieval period between the 1550th century, the golden age of the sagas, and XNUMX, the year in which the last Catholic bishop Jón Arason and conventionally fixes the end of Middle Ages Icelandic [3].

The origin of the sagas has long been the subject of discussion and has seen the opposition of two opposing theories: some scholars argued that these texts were nothing more than the transcription of a long oral tradition, the others considered them the original fruit of Icelandic literal genius. The debate, in more recent times, has gradually begun to recompose itself thanks to the attempt to reconcile the two approaches. While it is not possible to deny that certain elements of historical significance offered by the sagas can only be explained in the light of the oral tradition - this is the case of all those references of a cultural, social and legal matrix that chronologically precede the actual drafting of the sagas, but of which we have confirmed through historical and archaeological sources -, we also recognize the presence of a precise literary intent, perhaps already emerged at the time of narrative elaboration in the oral tradition [4].

Among the various genres and subgenres identified by scholars in the vast and heterogeneous corpus of the sagas [5], stands out that of íslendingasögur, the so-called "sagas of the Icelanders", ie the stories of those men and women who fled Norway and colonized Iceland, their ancestors and their descendants in the period immediately following Christianization (999/1000 AD). It is to this vein that the Gunnars saga keldugnúpsfífls, recently published in Italy by Iperborea, in the translation and edited by Roberto Luigi Pagani.

Set at the end of the XNUMXth century, that of Gunnar may be the last Icelandic saga to have been written, according to some scholars. It has been handed down to us in two versions - some extracts from the second, useful to supplement the first, accompany the Hyperborean edition - and it is a minor saga, composed in the fifteenth century and therefore "post-classical", as the sagas after the thirteenth century are defined. Appreciated by Icelandic readers of the following centuries, judging by the abundant number of manuscripts compiled between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, this interest was not shared by scholars for a long time. Fulvio Ferraro, in the afterword, clearly sets out the reasons [6]:

The philology of the early nineteenth century was above all in search of evidence of the heroic and legendary past of the Nordic peoples, of vestiges of ancient religion and mythology, and therefore turned above all to sagas - and poetic compositions - which seemed to reflect and document more faithfully this past. [...] To the interest in the legendary sagas (Fronaldarsogur) so the one for the so-called historical sagas took over, which narrate the stories of important figures in Icelandic history or reconstruct the destinies of the main Scandinavian royal lineages.

Of this work, which presumably was influenced by the knightly sagas and of the ancient time, the literary cut and the eccentricity with respect to the archetypal structure to which the other sagas of the Icelanders adhere more strongly must therefore be appreciated. This model first of all envisaged the declination of a well-defined genealogical apparatus that would allow tracing the characters presented to some colonizer of previous generations. [7], or some legendary figure [8], so as to insert the narration in a wider frame, almost as if it were "A piece of a sort of historical and genealogical mosaic" [9]. So much so that, in the classic sagas, it is difficult to identify a single protagonist and the narration hinges around multiple perspective angles, firmly anchored to the complexity of an original pluralism of voices.

This is not the case with the Gunnars Saga, which revolves around the troubled events of a single character, the same one who gives the name to the work: Gunnar, son of Þorbjörn, brother of Helgi, known throughout the districts as "the idiot of Keldugnúpur". This is because, we learn at the beginning of the narration, “he spent his time lying in the hearth room. He was not much loved by his father, as he often acted against his will. And because of his behavior he had become unpopular with the people. ' Why then pass on the story of a young man who is presented in all respects as a anti-hero and that it deserves, rather, one as severe as it is just damnatio memoriae? Because behind the mask of the indolent idler, the good-for-nothing, there is actually a prodigious warrior [10]. In short: Gunnar is a hidden hero. Emblematic, from this point of view, is the image used which reveals the allegorical unveiling [11]:

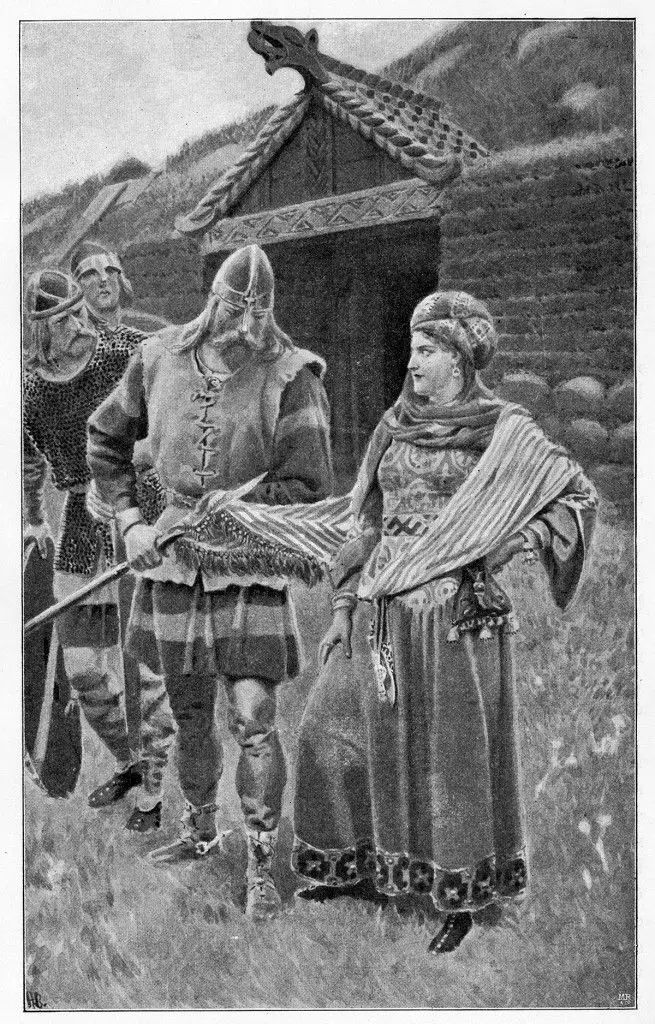

Gunnar took off his cloak and a great deal of ash rose from it. He folded it and threw it in the corner towards Helga. She picked it up and placed it beside her. Then they exchanged glances, and many were quick to swear they had met before.

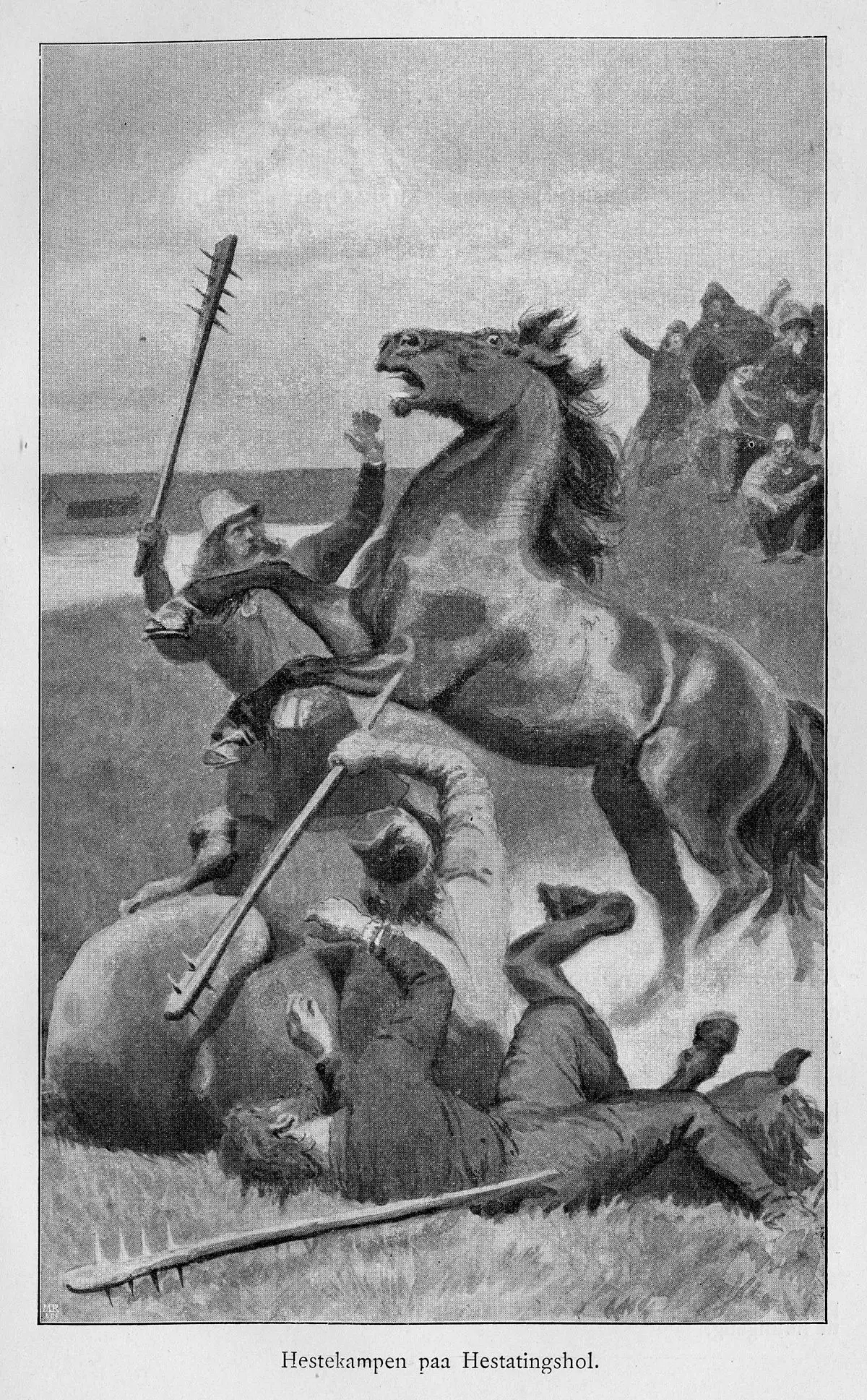

The narrative pretext for Gunnar's heroic revelation is given by a particular fighting contest (smile, in Icelandic) for which it was necessary to lift the opponent by the trousers, or the belt, and thus groped to make him fall [12]. This episode, placed at the beginning of the development of the plot, takes on significant importance when it provides us with the information necessary to have a general picture of the main characters, their characteristics, and the relationships that exist between them. In fact, if on the one hand we have Gunnar's family, with peaceful and cordial features, on the other hand we find Þorgrímur and his sons, Grímur and Jokull, of a violent and warlike nature. It will be precisely starting from the games, won by the sons of Þorbjörn, that the brothers of one and the other clan will become bitter rivals. Added to this is that Gunnar cultivated a secret relationship with Helga, also the daughter of Þorgrímur, "a beautiful and courteous woman [...] it was thought there was no better start in the whole region" [13]. Perhaps some of the hostility must have been due precisely to this liaison secret [14], as the relationship between the two is only revealed after Gunnar heroically (and slyly) killed both of his brothers [15]:

Jokull soon fell to Gunnar's hand. Grímur [...] he recognized the man immediately and attacked Gunnar with a large ax, but he parried the blow with his shield, while with the other hand he struck the opponent in the leg above the knee, amputating it. Grímur fell to the ground. With agile movement, Gunnar struck him in the throat, cut off his head and, returning to the door of the house, deposited it there. This done, he went to Helga's room [...]. “I've decided to leave,” Gunnar confided. "And how do you think you can keep the promise we made?" she asked. “That's exactly why I came. I want to renew it for you, ”he replied. [...] Having said that, they made a solemn promise that they would never take another woman and she another man [...] Gunnar kissed her with great enthusiasm and left.

At this point in the story, the Gunnars Saga it seems to become a real Bildungsroman before its time. Gunnar, after making a promise to Helga, embarks with his brother aboard Captain Bárdur's ship for the North. Arrived in Greenland [16], our hero - despite having previously demonstrated his incredible strength - decides to test himself and ventures alone to the glaciers [17], performing incredible feats. Later, after escaping the plots of one Earl of Norway who wanted him dead, will be the protagonist of raids and adventurous clashes with pirates. Only then, covered with honors and loaded with rich treasures, will Gunnar finally head home and marry Helga, becoming a local lord himself and founding a glorious lineage.

In short, the Gunnars Saga, in the form in which it is received:

It presents itself as a late literary tale that somehow attempts to place itself in the tradition of the Icelandic sagas, providing a heroic lineage to the people of a part of Iceland [the southeastern region of Síða [18], historically the most isolated] on which little material has been handed down or has ever been written, but using the literary tools of the period in which the drafting took place [19].

It is therefore not surprising if we do not find references to Gunnar's genealogy because the function of the saga is precisely to create a past in the form of a tale with an epic tone. So much so that the Saga è something alive in the imagination of the locals, as evidenced by various natural elements whose name is associated with that of the protagonist. This is the case, for example, of the Gunnarshellir ("Gunnar's Cave"), on the rock face of Keldugnúpur.

In conclusion, that of Gunnar in the constellation of the sagas remains a "Universe unto itself" [20] to take up the image used by Pagani in his remarkable introduction, of which we appreciate the wide contextualization of the work and the popular passion for this precious legacy of Icelandic medieval culture and literature. Among the other merits it should be noted that of a translation work that not only aims at philological rigor, but also at the transmission of that profound sense of language and of the narrative genre otherwise difficult to restore for the contemporary reader - and this despite the concrete difficulties presented. from such an attempt at conciliation.

Note:

[1] An exhaustive description of the battle is given in Vatnsdoela saga, published by Einaudi (1973).

[2] M. Scavazzi, Introduction in Ancient Icelandic sagas, Einaudi, Milan 1973, p. VIII.

[3] RL Pagani, Introduction in Gunnar saga, Iperborea, Milan 2020, p. 7.

[4] See Ibid.

[5] «However, this subdivision is largely the result of an a posteriori reconstruction, which began in the 8th century, and indeed there was no lack of vehement criticisms of the traditional system of genres […]. More recently, an approach has emerged that sees sagas as a "multimodal" genre, according to which the dense cosmos of stylistic, linguistic, thematic and expressive variations that characterizes the universe of sagas must be seen [...] as proof of 'fruitful and reciprocal interaction of different genres which with their dense interchange of specific elements have kept the tradition alive, making it evolve in new directions ». Ibi, p. XNUMX ff.

[6] F. Ferraro, Afterword in Gunnar saga, cit., p. 122.

[7] This is the case, for example, of the Laxdaela Saga: «Björn, the son of Ketill, replied:“ I will reveal my will to you instantly. I want to follow the example of more worthy men and leave this country; I don't think I earn anything by waiting for King Haraldr's servants who will persecute us to drive us off our properties, let alone suffer death at their hands ”. […]. So they made the decision to go […] to Iceland because they claimed to have heard of it very well "(tr. It. Edited by Silvia Cosmini, Iperborea, Milan 2015, p. 12 ff.).

[8] These references make it possible to trace the genealogies to the characters of the Landnámabók, the "Book of Settlements". This text, probably composed in the twelfth century, exposes the list of all the colonizers of Iceland following the coast in a clockwise direction, and providing succinct biographical information. None of the settlers of the Síða area, where the characters of the Gunnars Saga, is mentioned in the saga. See RL Pagani, Introduction, cit., p. 14.

[9] ibi, p. 15.

[10] In Icelandic there is a precise term to connote this type of character, that is kolbítur ("Carbon-beater"). In addition to Gunnar, Sigurður the Silent (Sigurðar saga), Refr Steinsson (Króka-Refs saga) and Starkaðr (Gautrekr saga, Iperborea 2004). See Ibi, p. 12).

[11] ibi, p. 97.

[12] See Ibi, note 3, p. 116.

[13] ibi, p. 47.

[14] Note, in the citation above (see note 11), the topos erotic of the cloak, typical of the courtly imaginary.

[15] RL Pagani, Introduction, cit., p. 63 ff.

[16] See Ibi, note 8, p. 116.

[17] Notice the echo of the topos of the rite of passage.

[18] For an in-depth study (also photographic) about the places of the Saga, we recommend this article written by the curator of the work on his personal blog: https://unitalianoinislanda.com/2020/05/13/i-luoghi-della-saga-di-gunnar/.

[19] RL Pagani, Introduction, cit., p. 17.

[20] ibi, p. 21.

A comment on "The Saga of Gunnar, the idiot of Keldugnúpur"