The collection of short stories published by ABEditore ranges from the XNUMXth to the early XNUMXth century, with stories that refer to British, Italian, Japanese, Korean and Indian folk traditions.

di Marco Maculotti

Among the local publishing houses that in recent times have stood out for the quality and originality of the publications (also and above all for the curation of the graphics, which adds to the editorial seriousness), a prominent place undoubtedly goes to AB Editor. Among the latest releases to report to fans of folklore and mythology, here we want to spend a few words on Goblin, edited by Peter Guarriello (founder of the publishing house Dagon Press and magazines Lovecraftian Studies e zothique), a collection of short stories written and published mainly at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (but there are also older ones) focusing on imaginative world of Fairies, that is, those heterogeneous entities of the invisible world that for centuries if not even for millennia have been protagonists of popular traditions from all over the world, from Europe where they achieved a fame that is difficult to replicate during the Victorian age, to Asia: not randomly in Goblin also stories, inspired by traditional folklore, from Japan, Korea and India, which among other things deserve a special mention in this already appreciable publication.

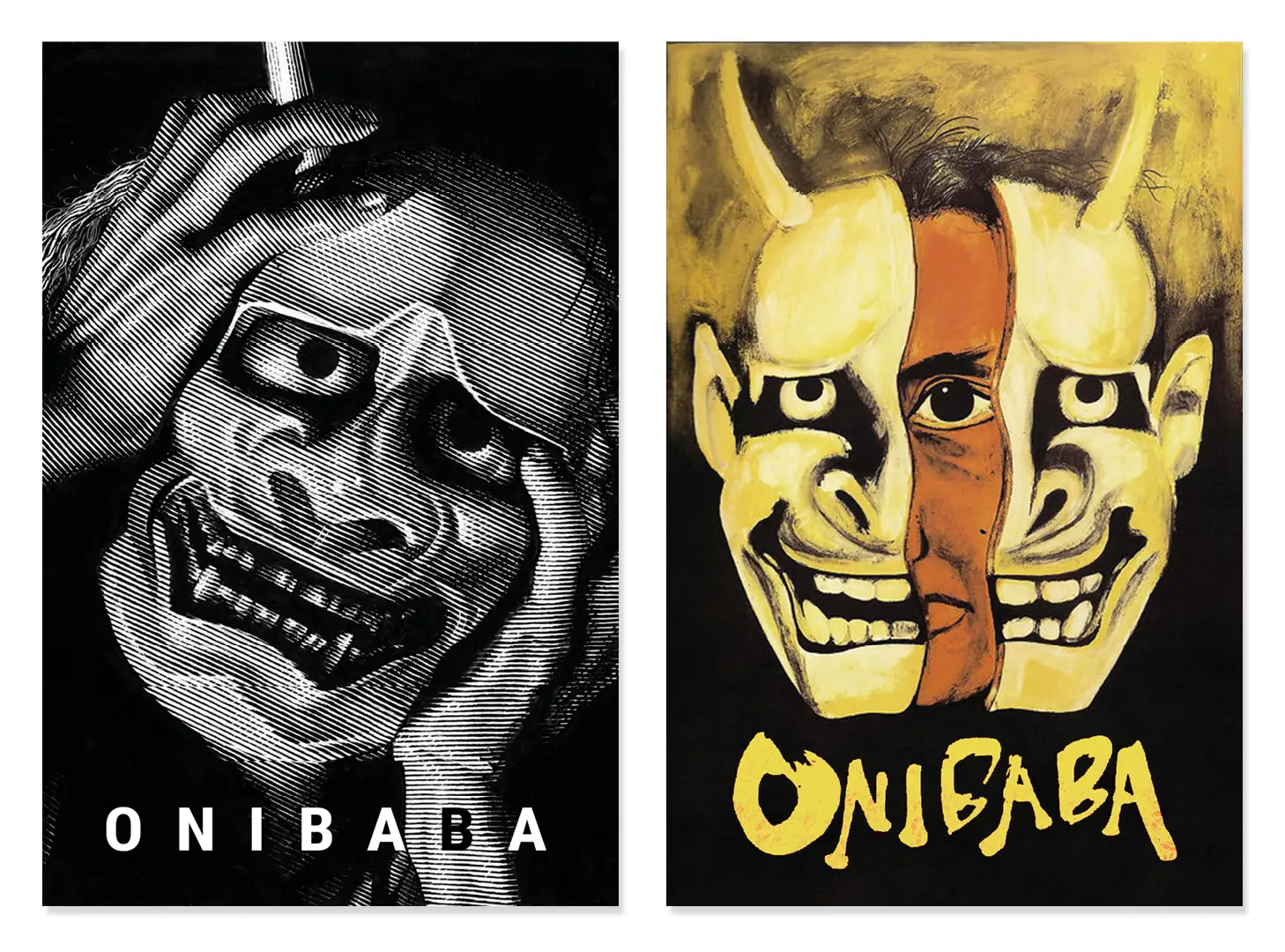

La Japanese tradition in particular, it literally swarms with feral creatures, defined by innumerable names: come on tengu, mountain goblin, ai kappa, sprites dwelling in lakes, rivers and ponds, up to the most all-encompassing denomination of youkai, supernatural creatures endowed with disturbing and demonic characteristics. The story The demon of Adachigahara, which we can read in this collection, is inspired by a true legend of rural Japan, centered on one youkai who was said to take the appearance of a defenseless old woman and then ferociously attack her guests. The belief is so strong in the plain of Adachigahara that it is still possible to visit a small museum that preserves the mythical cauldron and the knife that this demon used on its victims. [1]. This youkai is known by the name of Omniba and inspired, among other things, a notable film, among the best of the current folk horror Nipponica, entitled precisely Omniba (written and scripted by Kaneto Shindo in 1964). This story instead bears the signature of Theodora Ozaki (1871 - 1932) and was originally published in 1903, in his anthology Japanese Fairy Book, whose publication was greatly encouraged by the Scottish folklorist Andrew Lang, author of numerous collections of folk- e fairy tales [2].

This place was said to be haunted by a cannibal goblin who looked like an old woman. Occasionally some travelers disappeared and she never heard of them again. The old women around the braziers of the hearth in the evening, and the girls who washed the rice in the wells in the morning, whispered terrible stories ... they said that the missing were lured into the house of the demon-elf and devoured alive, as the goblin ate only meat Human. No one dared venture near that haunted place after dark, those who could avoided it even during the day, and all travelers were warned about that scary place. [3]

- sprites of the Korean tale (An Encounter with a Hobgoblin) by Im Bang and Yu Ryuk, two historical authors who lived between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, are instead gods doggabi o dokkaebi, goblins who possess extraordinary abilities including metamorphic and who kidnap humans during the night, involving them in sessions of struggle [4] and making him do it "cosmic" flights reminiscent of those occasionally evoked in modern art abduction aliens, as well as in the shamanic testimonies of Asia and the Americas:

[…] He took me by the hands and threw me into the air, until flying I almost found myself in the sky. […] In my I fly through space I saw all the cities of the three provinces of the county, clear as day. A Chulla threw me again. And once again I flew up to the sky, then fell back to the north… until I found myself at home, stretched out and amazed, under the veranda terrace. [5]

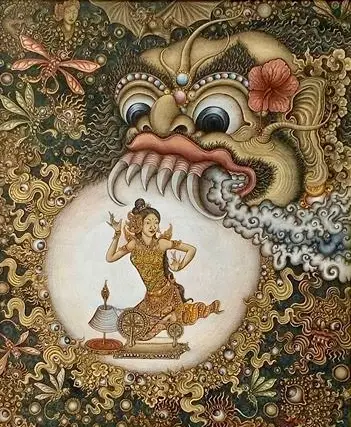

Analogous to the youkai of the Japanese tradition are i Rākshasa, shapeshifting Indian goblins who feed on human flesh and all that is rotten, and their female equivalent Rākshasi, protagonists of the story of WHD Rouse (1863 - 1950) The city of goblins, originally published in 1897, that before devouring their own unsuspecting victims, mainly sailors similar to the myth of the Sirens, are used to sexually mate with them and take them as husbands [6], topos classic of the most varied world traditions concerning the supernatural bride, spread throughout the world and also taken up in fantastic literature, for example by Arthur Machen in his novel The Hill of Dreams (1907)

On the other hand, the Munaciello of the last story in this collection, written by Matilde Serao and taken from the anthology Neapolitan legends (1881). Outwardly similar to the genius cucullatus of the ancient Romans and Gauls [7], the “monachello” is a recurring figure in Neapolitan folklore, but which is also present under various names in the rest of the Italian peninsula, from the Alps to the southern tip of the boot. Considered a sort of domestic spirit that, like the Irish Leprechaun, conferred sudden wealth, provided he did not reveal his existence by talking to third parties, he was described as a sort of deformed person, with the face of an old man, dressed in a monk's robe, which included a red or black hood [8]. Having become a recurring figure in Neapolitan popular beliefs over the centuries, the Munaciello ended up becoming a kind of "black man", responsible for every disruption and tragedy that could happen to the inhabitants of the Campania metropolis, especially in the "lower" and peripheral neighborhoods :

It was he who drew the mephitic air to the lower quarters, which brought fever and sickness there; he who, looking into the wells, spoiled and made the water rot, he who, by touching the dogs, made them angry […] it is he who makes the wine sour from the bottles; it is he who gives the jinx to the hens who demean and die; […] It is the evil hand of the elf who has prepared these great and small misfortunes. When the baby cries, he cries […] is the munaciello that you put devils in his body; when the girl turns pale and red for no reason, she becomes melancholy, she smiles looking at the stars, sighs looking at the moon, and cries in the quiet autumn nights, it is the munaciello that spoils her life in this way [...] [9]

Obviously, most of the tales refer to the European tradition, especially British, which, having always been influenced by the folkloric beliefs of the ancient Gaels, attributes to Fairies, sidh e Goblin a considerable importance, difficult to find in other parts of the world. In the story The Knockgrafton Legend of the Irish antiquarian Thomas Crofton Croker (1798 - 1854) convey various themes of folklore fairy widespread with minimal differences throughout the Geal area: from elven music which attracts the traveler towards the enigmatic entities, engaged in their games and dances, to the nursery rhyme sung by the latter focused on the declamation of the days of the week, up to their mysterious ability to remove from a hunchback the ominous appendix that makes him cripple ... and make it "tick" on someone else [10].

Ne The Skriker di James Bowker (1878) the narrator is out for a walk at night and his survival depends on reaching and crossing a bridge, according to a topos proven both in the shamanic tradition (the bridge tight as a hair to overcome to access the World of Spirits) and in the fantastic literature influenced by folklore: think for example. to The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, a short story by Washington Irving published in 1820 and later brought to the big screen first by Disney in 1949, then half a century later by Tim Burton, in the 1999 film with Johnny Depp. To undermine the night traveler we find, as the title suggests, one Skriker, evil goblin and genius loci of rural Yorkshire and Lancashire wandering invisibly through the woods at night, letting out terrifying screams [11], by means of which, similarly to the Banshee of Irish and Scottish folklore, he reveals his sinister omen of death to anyone who has the misfortune to meet him on his way.

The loot of the elf di Algernon Blackwood (1912) - one of the masters of supernatural horror literature who not infrequently, as in his epochal tale The Wendigo (1910), he went back to the myth and folklore of premodern societies - brings to the stage the aforementioned Leprechaun Irish and its characteristic of making small shiny objects disappear and then make them reappear only when the owner stopped looking for them [12].

Ne The witches pony di Andrew Long (1900) the protagonist is a Nuggle, a typical sprite of Shetland folklore renowned for his ability to take the appearance of a black or gray horse and to drag his victims into the depths of lakes and rivers, causing them to drown, who had the unfortunate idea of riding him [13]: A modus operandi which the Highland Scots attribute to Kelpie.

The further the pony advanced, the more the sea rose; eventually, the waves covered the boys' heads and they all perished by drowning. [14]

Two stories differ to a certain extent from the folkloric tradition. The first, one of the most deserving collated in this collection, is Il Brownie of the Dark Valley di James Hogg, considered by some critics as "the maximum of Scottish Gothic in the early nineteenth century" (the definition is by Giorgio Spina) [15]. Here the elf, contrary to the traditional Brownie, initially appears as a human being in flesh and blood, in the role of "an inscrutable and mysterious servant of a degenerate family", as Guarriello defines him [16]. Nonetheless, the physical description of him brings him appreciably closer to some ferocious characters in the literary production of Arthur Machen (such as the Jervase of the Novel of the Black Seal), as it is said that

he had something different from the rest of men. He had the physique of a little boy and the appearance of an old man. Some thought he was a hybrid, a cross between a Jew and a monkey; others thought he was a sorcerer, still others a kelpies or a goblin ... but the prevailing opinion was that it was a real brownie. [17]

Interesting in this story is the curse that seems to hang on the "evil and degenerate" house [18], on its members and on the villa in which they live, which ultimately leads more than one of them to death and madness. A sort of curse seems to strike also for the protagonist of the second story who detaches himself rather sensibly from the traditional dogmas on feral entities: The elves' eggs di Joseph Berg Esenwein e Marietta Stockard. The latter, having witnessed the "hatching" of the eggs during a walk in the woods that give the story its title (an invention of the two authors, unknown to traditional folklore Fae), himself undergoes a disturbing mutation.

They complete Goblin, in addition to the titles we have briefly mentioned, four other stories - The Brownie of Valferne by Elizabeth W. Grierson, The face of the Goblin by Mrs. Molesworth, The saint and the stone elf by HH Munro (better known under the pseudonym of Saki) e The elf of the rose by Egisto Roggero - and above all, at the beginning, an exhaustive essay by Guarriello (History of the elves: origin, rise and decline) on the folkloric tradition concerning fairy beings and the most important scholars of the same in the last centuries, which concentrates in about thirty pages everything the reader should know before diving into the reading of the actual collection. At this point, we just have to wish you happy reading, preferably night!

Note:

[1] P. Guarriello, introductory note to T. Ozaki, The demon of Adachigahara, in Guarriello (edited by), Goblin, ABEditore, Milan 2020, p. 167

[2] Ibid, p. 168

[3] Ozaki, op. cit., p. 169

[4] Guarriello, introductory note to I. Bang and Y. Ryuk, The spritesin Goblin, cit., p. 178

[5] Bang and Ryuk, op. cit., p. 184

[6] Guarriello, introductory note to WHD Rouse, The city of goblinsin Goblin, cit., p. 189

[7] On the Genius Cucullato, cf. W. Deonna, Gods, Geniuses and hooded demons: from Telesforo to "Moine Bourru", Medusa, Milan 2019

[8] Guarriello, introductory note to M. Serao, O 'Munacielloin Goblin, cit., p. 215

[9] Serao, op. cit., pp. 220-223

[10] All these reasons are reported in the monographic work on tradition fairy by the Theosophist WY Evans-Wentz, The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries, 1911

[11] Guarriello, introductory note a The Skrikerin Goblin, cit., p. 55

[12] Guarriello, introductory note to A. Blackwood The loot of the elfin Goblin, cit., p. 95

[13] Guarriello, introductory note to A. Lang, The witches ponyin Goblin, cit., p. 159

[14] Lang, op. cit., p. 163

[15] Guarriello, introductory note to J. Hogg, The Brownie of the Dark Valleyin Goblin, cit., p. 111

[16] Ibidem

[17] Hogg, op. cit., p. 127

[18] Ibid, p. 128