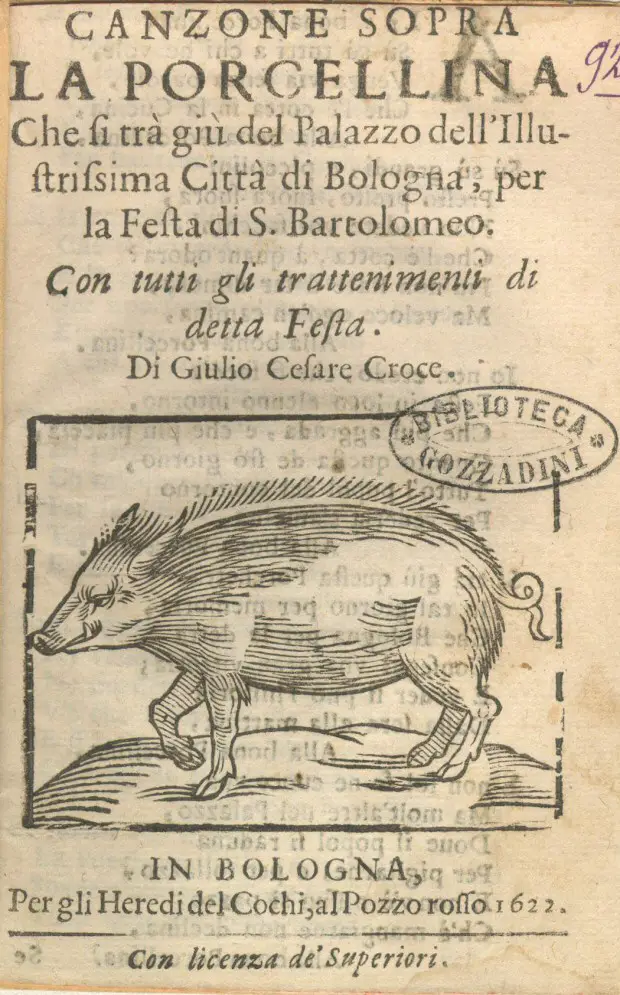

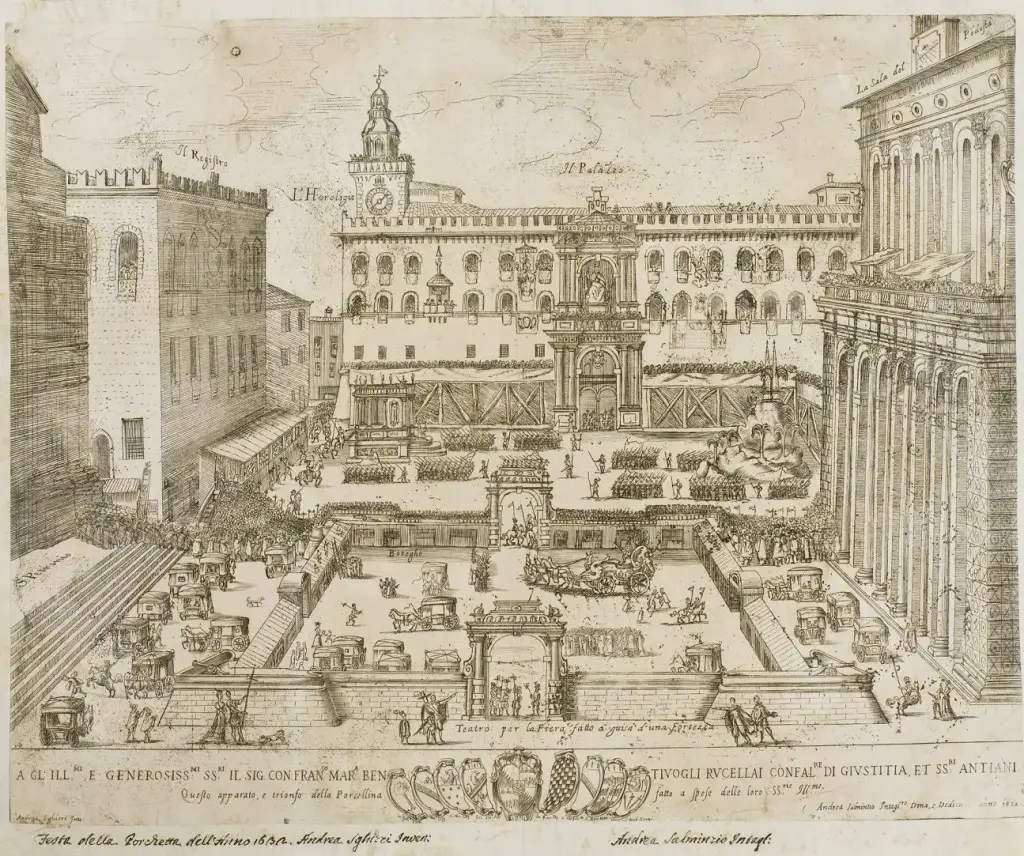

Lorena Bianconi is the author of the booklet "At the origins of the Bolognese Porchetta festival" (Clueb, 2005), the celebratory occasion of August 24 which characterized the Bolognese summers for at least 500 years. The author questions the supposed medieval origins of the festival and through an anthropological reading of its rituality, the comparison with ancient pre-Christian cults and analyzing the ritual use of the pig in the ancient world, she concludes that it could be the relic of ancient rituals. pre-Christian connected with seasonal change.

Here you can read two extracts, chosen by us, of two essays that Dr. Bianconi has written on the subject (one of which in four hands with the colleague Maria Cristina Citroni) and, if you would like to learn more, you will also have the opportunity to download the two complete essays in PDF format for free.

WISE # 1

SAN BARTOLOMEO AND THE PORCHETTA.

Historical-anthropological investigation of a Bolognese folk festival

Lorraine Bianconi

(selected excerpt :)

[...] Since there is no link between the Bolognese tradition and the life or martyrdom of San Bartolomeo, it could be assumed that it was part of a legacy left by ancient pagan rites, which were absorbed in the early medieval era in the cult of San Bartholomew. The ritual use of the pig in the ancient world is indeed attested by a variety of sources. In various cultures this animal has always enjoyed a strong and ambivalent symbolic charge, which manifested itself through the most varied forms of veneration, sacrifice and common meal, or absolute repulsion and avoidance. In Etruria, in Greece and also in Rome the sacrifice of the pig occurred for example in very delicate moments of social and individual life, the stipulation of alliances between rulers and marriages: "Romans, Etruscans and ancient Greeks killed the Porca in the alliances of the royal , but also the magnates of Etruria did it, at the beginning of their wedding ", and Festus confirms that" at the end of a war a slut was sacrificed in making peace ". It is therefore legitimate to say that the civilizations that preceded us often attributed to the pig, in particular to the sow, the status of sacrificial animal.

To this we can add that also the preparation and the type of cooking that the porchetta bolognese had to undergo were very close to those for which the sacrificial animals of the ancient world were intended. In Greece, the preparation of an animal destined for immolation generally consisted in the gutting, extraction of the entrails and subsequent boiling or roasting of the victim, whose body had in any case to remain whole. These prescriptions were also valid in the Roman world: the Porcus Trojanus, a pig that was sacrificed on the occasion of alliances and weddings, before being served had to be "gutted, gutted, filled with pepper, herbs, garlic, salt, fresh fennel and then cooked whole in the oven ”and the female was considered the best to cook in this way. Well, this was the same treatment that the Bolognese porchetta underwent, before being thrown to the people: it was in fact gutted, filled "with the finest and most perfect speciaria stuff" and then roasted whole, "so as not to outrage him, or wrong" .

References to the sacrificial practices of the ancient world are also found in the equipment that was used in Bologna to present the porchetta just before throwing it to the people. Once cooked, the animal was placed on a particular table ("Above a board she can be seen / cooked well and kept)", which was used by porchetta sellers at least until the nineteenth century and apparently was commonly called "matra ". This axis should derive from a table, the "mactra", which the ancient Romans already used.

We must also reflect on the fact that, as part of the feast of August 24, the Scalco had a fundamental task: he had to cook and present to the public the porchetta that would be thrown away. Specifically, he prepared the animal by removing the entrails and filling the abdomen with spices and aromas, roasting it and placing it on display on the matra, following a sort of ceremonial. Once the roasted animal was presented to the people, he first had to chop the head, which was thrown separately, before or after the rest of the body and then cut all the rest, which from the matra was thrown on the bystanders. All this, announced each time by trumpet blasts, as if to signal the solemnity of the moment. With respect to this, it should be remembered that in Greece, “starting from the fifth century. BC the various operations of the sacrifice are ensured by a character, the mageiros, the butcher-cook-sacrificer, whose functional name expresses the convergence between the killing of victims, the trading of meat and the preparation of meat foods ”.

In Bologna, therefore, on 24 August, Scalco essentially assumed the three specific functions of the Greek mageiros: he was a butcher, because he gutted; he was a cook, because he flavored and roasted meats; finally, he too was a "sacrificer", because, announced by trumpet blasts, he presented the porchetta to the people and solemnly cut the meat, following a specific procedure. We can therefore note how the practices relating to the preparation and cooking of the porchetta of the Bolognese festival, the equipment used and the role of the Scalco, actually recall various elements of the religious-ritual world of the ancient Greeks and Romans, hence the hypothesis that the use of porchetta during the feast of 24 August could be the residue of some form of pre-Christian rituality is not entirely without foundation. On the other hand, even today it is not rare to find in the Italian popular traditions that almost always accompany religious holidays, the remains of ancient more or less archaic rites. This, especially as regards the holidays which are closely related to the change of season and to the phases of agricultural life.

The most ancient forms of religiosity actually tended to read certain phenomena of nature, especially those that occurred regularly (solstices, equinoxes, arrival of rains, etc.), as particular moments of contact with the sacred. For this reason, the arrival of such phenomena was often accompanied by celebrations and by carrying out particular ritual actions. In this regard, it is perhaps useful to know that in many areas of Italy (in Lombardy, Campania and Abruzzo, in Tuscany, in part of Emilia and on the Modenese Apennines) August 24 is still indicated today as a period characterized by changes climatic, meteorological, as well as agricultural, considered announcement of the end of the summer season.

This is suggested by some proverbs, widespread especially in mountain areas, which quite explicitly identify August 24 with the moment when the first signs of the change of season appear towards the end of summer. In Veneto, for example, the mountaineers, seeing the first signs of winter arrive, say "Bartolomé don't do it for me", or "San Bartolomio, this su laa to arzeliva e va 'con Dio" (arzeliva is the hay of the second mowing that takes place in the mountains at the end of August). In Valtellina they say “San Bartulamé, muntagna bèla te lasi dedré. In San Bartulamé i muntagni i stands for itself. In San Bartulamé, the mountain la se varda indirée "(" San Bartolomeo, beautiful mountain I leave you behind. In San Bartolomeo the mountains are on their own. In San Bartolomeo you look back on the mountain. " shepherds who had climbed the high pastures in early July, begin to descend towards the valley with the animals). In Val Saviore the proverb "Guai a trùas a Linsi oa l'Adamé, after San Bartolomé" is widespread ("it is very dangerous to be on the highest peaks after August 24". Linsì indicates the Lincino mountain hut above Saviore, at the foot of the Adamello glacier). [...]

(full text, with notes and bibliographic suggestions :)

WISE # 2

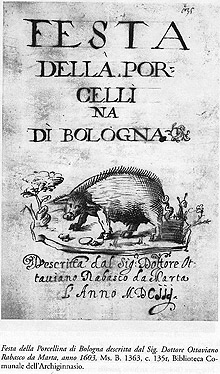

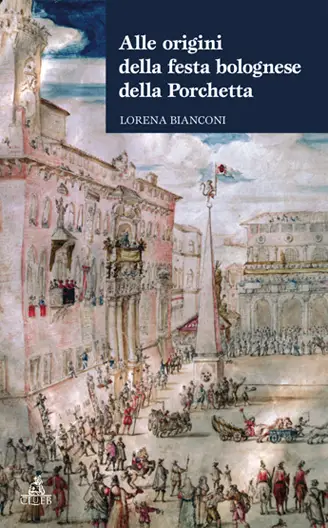

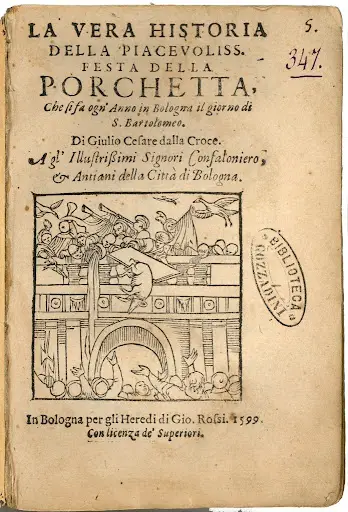

To the good Porcellina: Giulio Cesare Croce and the Bolognese festival of Porchetta

Lorraine Bianconi e

Maria Cristina Citroni

(selected excerpt :)

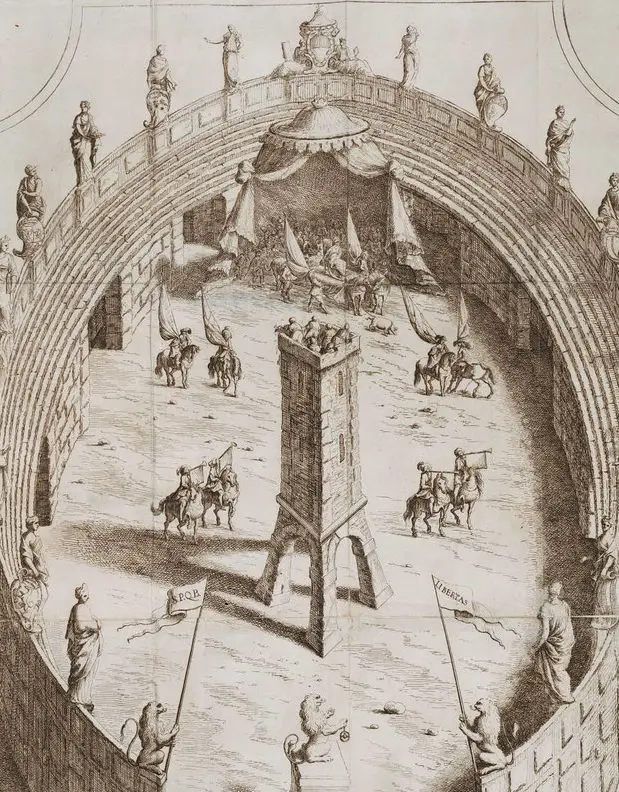

[...] The Bolognese celebration should then be understood not simplistically as a cynical palliative for the hunger and misery of the people, but as a real collective ritual game, based on the concept of gift and cheerful waste, aimed at introducing, semel in year, in a world of equality, of "superabundance", of "happiness" and almost otherworldly peace. In fact, we have already mentioned elsewhere an interpretation which tends to see in the Bolognese celebration almost a Social "rite of pacification", aimed at obtaining a momentary but symbolically important harmony between the classes, a more or less explicit expression of the desire shared by the population "for a generalized tension towards unity, cohesion and social harmony".

It should be remembered in this regard that in the ancient world the sacrifice of the pig was often carried out on the occasion of peace treaties and the stipulation of alliances: in this sense the feast of the Porchetta could therefore be interpreted, on the basis of that ancient and authoritative Etruscan tradition , Greek and Roman, also as a symbolic annual celebration of a "peace treaty", of a pact of "collaborative" alliance between nobles and people, aimed primarily at sanctioning their own fundamental mutual dignity and necessity.

In fact, it can be added that, in particular between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, this festival, supported and sponsored by the politics of the elderly consuls of the Bolognese senate, despite the apparent banality of its playful dynamics, seems to have a precise and not accidental background scenario in its utopian-equal way, characterized by the sharing between nobles and people, as well as the abundance of delicious food, also the splendor of a magnificent context and therefore opulence and prosperity. This peculiar political-social modality of the sixteenth-century celebration could therefore be considered a happy expression of that "vein of counter-reformist political culture", recently highlighted also by Gian Mario Anselmi, aimed at "benignly" and "generously" superior and divine order »the« tumultuous and riotous “sublunary” events, human and earthly ». [...]

The identification of an evident, and perhaps even obvious, playful aspect seems to have a certain consistency in the structure of the Porchetta festival, even if this investigation certainly needs further investigation. Here we can only mention, among the possible connections, the connection of the playful value of the party with the psycho-social and cultural function of the game, studied, for example, by Johan Huizinga in homo ludens. [...]

It is perhaps useful here to remember that, as in the Middle Ages, between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries the "universal comic principle" still permeated that "popular" vision of the world of which Julius Cesare Croce was the spokesman. A regenerating and renewing power, rice was even, following Mikhail Bakhtin, the main vehicle for the expression of the "second truth about the world", of a different way of perceiving and interpreting reality, no less important than the serious one, which since ancient times it accompanied the "official culture" as its mirror and "opposite" image. Each festival, according to Bakhtin, "in addition to its official, religious and regime aspect, still had a second aspect, popular and carnival, the principle of which was laughter and the material-bodily "low"».

And in fact, even in the "piazza" festival of Porchetta, even the most mysterious and "terrifying" aspects of life, as well as the heavy problems of civil coexistence, could be the object of "auspicious" laughter. Let us think, for example, of the fights or the "peaceful battles of the Fists" that were regularly unleashed among the people over the disputes over the gifts thrown: they too can be considered an expression of this Bakhtinian "regenerating comic principle", as it is possible to interpret them as "Ritual barrel" harbinger of fertility. Although the fist fights can be read as a cathartic dramatization of the social conflict generated by the unequal sharing of food resources, the comic and the public ritualization, partly to weaken their potential destructiveness. By resorting to the metaphorical "lowering", the "diminution" produced by rice, the aim was thus obtained to lighten the dramatic and ineluctable aspect of life. Thanks to the testimonies of Croce, the popular experience and the meaning of the Bolognese festival of Porchetta now appear to be characterized by great complexity.

A complexity that is basically the complexity of life, emblematically relived in an afternoon at the end of August. An intertwining of experiences and emotions "of opposite sign", lived simultaneously within the liberating framework of the «universal rice"And general fun: on the one hand the vitality, the joyful carnality of games and pranks, the abundance of flesh with a scent" so sweet, and grateful, that a half-dead would be affected ", on the other hand, the rational need to reallocate violence, "sacrifice", social conflict in the utopian metaphor. An intertwining of meanings which, summarizing the vitalistic and exuberant atmosphere of the party, has already been defined elsewhere as a sort of annual "regenerating plunge" into the "primeval chaos", however, aimed at symbolically creating a new impetus that brings beneficial change, in the sign of collective optimism, prosperity and peace. [...]

(full text, with notes and bibliographic suggestions :)