Francis Ford Coppola's monumental film dedicated to the famous figure of the Count, released in theaters thirty years ago, managed to frighten and excite audiences around the world, thanks to its powerfully visionary style and the intensity of actors such as Gary Oldman and Anthony Hopkins in the lead roles. But in addition to the undeniable originality with which the "myth" of Dracula is reworked, did the film really respect a fidelity to the novel, as promised by the title? And how many particular references, allusions and influences can be traced in the scenes of this horror still fascinating and complex today?

di Jari Padoan

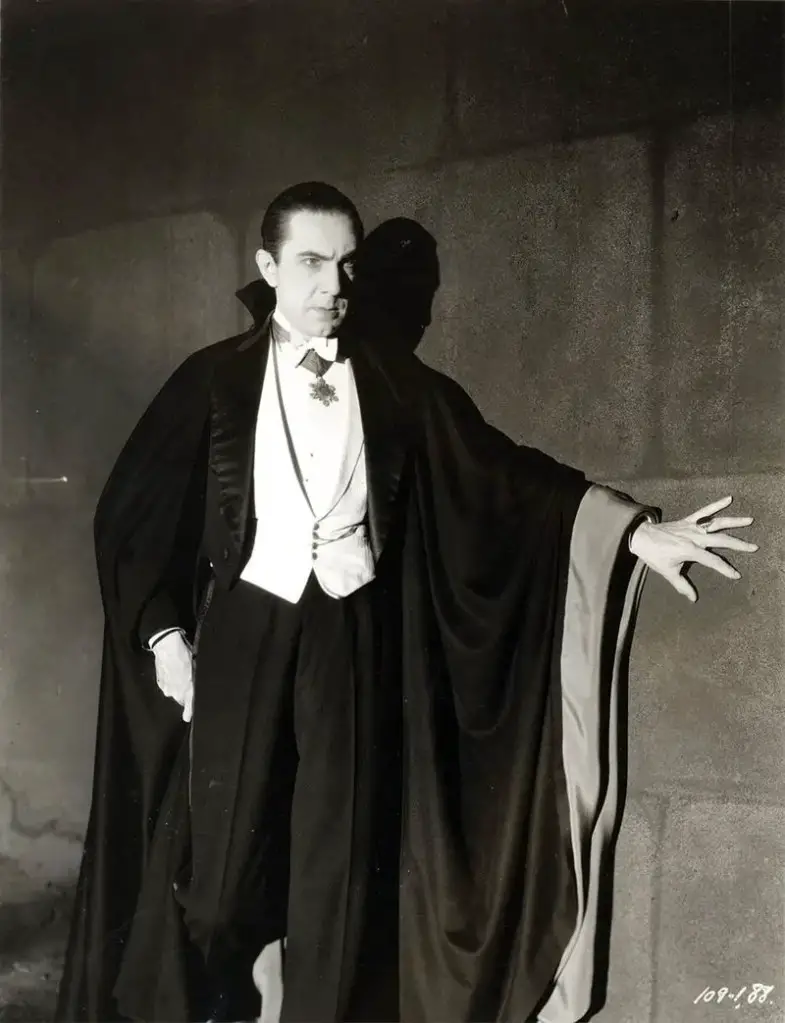

I ... I'm Dracula, and I welcome you to my home…; those who belong to the generation of the writer (that of the late eighties), hearing this joke will easily remember a demonic Gary Oldman wrapped in a damask cloak with a somewhat sanguine hue, who thus welcomes Jonathan Harker / Keanu Reeves to the ramparts of the most famous castle of fiction and cinema horror. We are in fact in one of the first scenes of the Bram Stoker's Dracula, shot in 1992 (in Italy it came out the following year, with the title, in fact, Dracula by Bram Stoker) from that Francis Ford Coppola who marked the last half century of international cinema, thanks to films such as Apocalypse Now and the saga of Godfather. At the time, this new Dracula represented many things: yet another masterful work in the career of the New York director, the most viewed vampire-themed film in the history of cinema [1], as well as an original and powerful one summa of the "tradition" dedicated to the most famous Vampire (and not only, given the numerous cultural references and cinematographic citations that can be appreciated during the film, as we will examine), which already at the time covered a chronological span of seventy years and counted numerous works, from the fundamental Nosferatu from FW Murnau to the grotesque Blood for Dracula by Andy Wharol, obviously passing through the iconic Dracula interpreted several times in the cinema by Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee. Furthermore, right from the title, the film declared a total (or almost) fidelity to the text by Bram Stoker (1847-1912), something that for the previous Dracula of the large and small screen had been more or less approximate or relative.

The idea of a new and above all "authentic" film version of the novel is due to the screenwriter Jim V. Hart, particularly active in the American fantasy cinema since the early nineties: for example, the screenplays for Hook by Steven Spielberg, of Contact by Robert Zemeckis and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, shot by Kenneth Branagh in '94 in the wake of the great success of Dracula by Coppola. The writing of the film was commissioned to Hart as early as the XNUMXs by Columbia Pictures producers Michael Apted and Robert O'Connor, the only ones interested in the project in an industry, the Hollywood one, which would no longer have easily bet on yet another version of the character. had been faithful or not to the original novel (from which each Dracula film had, basically, quite far away) [2]. Hart's text was also supported by the advice of Leonard Wolf, translator, writer and illustrious "vampirologist", as well as curator of The annotated Dracula (annotated edition of Stoker's novel, published in Italy by Longanesi in 1976). After a few years, the script of what could have become the new Dracula finally came into the hands of Francis Ford Coppola thanks to the interest of a very young actress of his acquaintance, Wynona Rider (at the time nineteen and fresh from the success of Edward scissor hands by Tim Burton), who had read the text and was delighted with the character of Mina Harker. Coppola's reaction (which, remember, before the stratospheric successes of the seventies had debuted in 1963 with dementia 13, a gloomy "b-movie”Produced by the master of independent horror Roger Corman) was decisive: Count Dracula would make his umpteenth return to the cinema, and he would personally take care of the project from behind the camera.

Coppola declared that he dedicated himself to the making of the film "guided by the history of cinema" [3]: as mentioned, his Dracula could not fail to deal with the crowded series of previous films directly or indirectly inspired by Stoker's book, and would have had the demanding burden of re-proposing the character in a new and original version, while maintaining an unprecedented coherence with the novel. A challenge that is far from simple, considering that, as the film historian David J. Skal pointed out, Count Dracula (also and above all thanks to the various films dedicated to the character) was probably the most famous fictional character of the twentieth century [4]. In fact, in the opinion of Donald A. Reed, former president of the Count Dracula Society, at least two hundred films about the character would have been made from the beginnings of cinema, but according to Jim V. Hart they turned out to be one more dull than the other, when compared to wealth. of Stoker's novel [5].

NOSFERATU DI MURNAU AND THE OTHER EARLY CINEMATOGRAPHIC DRACULA

What was really the first film inspired by Dracula it is a controversial question, since to try to solve it one would literally get lost in the shadows of the cinema of the origins: if the undisputed masterpiece is had in 1922 with the aforementioned Nosferatu, it seems that just before, between 1920 and 21, two were shot Dracula, respectively in Russia and Hungary, films that did not "survive" their time and about which very little is known [6]. Nosferatu-Eine symphonie des grauens and its director Murnau faced a notorious legal battle waged by the author's widow Dracula, Florence Balcombe Stoker (also known to British cultural circles for a youthful relationship with Oscar Wilde), who sued the German filmmaker for violation of copyright: the film, which stages the central elements and characters of the story, appears in fact as an unofficial transposition of the novel, even if it seems that in reality Murnau did not pursue at all, or not exclusively, this intent [7].

The title of the film itself, however, is directly taken from the pages of the novel, being the term nosferatu (or more correctly nefartatu, "False brother") [8] a folkloric expression to indicate the devil, as Jonathan Harker discovers among the Carpathian people. Apart from that, not only the two unrecognized ones would have escaped the attention of the meticulous Mrs. Stoker Dracula produced in Eastern Europe, but also a hard to find Drackula's death (sic) also shot in Hungary in 1912 and, from what the scholar of fantastic cinema Lokke Heiss has reconstructed, also in this case far from following the lines of the original novel, and much more inspired instead by the Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux [9].

Nosferatu (which Francis Ford Coppola points to as the greatest vampire movie) [10] staged the figure of Count Orlok, who was none other than Dracula of course, in whose shoes he played the "mysterious" theatrical actor Max Schreck whose threatening silhouette has become famous. Maintaining at least in part a certain proximity to the Dracula of the novel, Count Orlok is represented as a repugnant being whose appearance resembles those of a rodent: he is in fact characterized by abnormal incisors, while to admire the proverbial bloody canines one will have to wait for the Dracula by Terence Fisher with Christopher Lee, produced by Hammer Film in 1958. The first official and authorized transposition of the novel will be the theatrical version, staged in London in the mid-11s by John L. Balderston and Hamilton Deane (an Anglo-Irish playwright and impresario friend of the Stoker family) [XNUMX], who will model the features of Dracula as a dark and morbidly charming aristocrat. Rather than to the Count created by Stoker's pen, the style of the theatrical Dracula would therefore be closer to the character of Lord Ruthven, or the first authentic literary vampire of modern fiction (protagonist of the story The Vampire by John William Polidori, published in 1816). This image of the character of Dracula will soon be revived and consolidated in the first official film based on the novel, the famous American production of the same name by Universal in 1931 directed by Tod Browning and with Bela Lugosi, henceforth icon of thehorror, as the vampire.

THE DRACULA OF COPPOLA

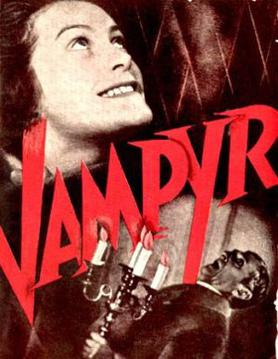

These well-known events related to the history and development of the literary and cinematographic Dracula are just some of the assumptions and influences that are found in Coppola's film, dominated from the first scenes by a dreamlike and baroque style. In addition to the special effects and make-up of Greg Cannom that allow the realization of the rather realistic vampirism scenes, much of the credit goes to the photography of Michael Ballhaus and to effective editing gimmicks. For example, the arrival of the carriage whose coachman is Dracula himself, who will have to pick up Jonathan Harker in the desolation of Passo Borgo to take him to the castle (exactly as it happens in the novel, then in Nosferatu and in Dracula Browning, although in this case the character of Harker was replaced with that of Renfield), is mounted on the contrary: the effect is alienating and disturbing, managing to convey a feeling of supernatural / unnatural, and will return in other scenes of the film (for example in the highly erotic encounter between Harker and the three brides of Dracula, among which one can notice a very undressed Monica Bellucci). It is also very impressive the "demonic" shadow of Dracula, which moves deferred or in total independence with respect to the movements of the aforementioned, and which in reality, to the eye of every horrorphile, turns out to be a clear homage to the terrifying Vampyr, shot in 1932 by Carl Theodor Dreyer (and freely inspired by some “vampiric” tales by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu).

In addition to the successful "revival" on the screen of the epistolary style of the novel, obtained with the voiceovers of the protagonists whose letters, notes and diaries (all almost literal extracts from the pages of the book) act as an introduction or commentary on many scenes, Hart and Coppola are responsible for the bold discovery of establishing the origins of the new Dracula by developing in the film the historical figure who inspired Bram Stoker to shape his character. That is, that of Vlad III Dracula (1431-1476), passed into history as Vlad Ţepeş or "the Impaler", voivode of the Order of the Dragon (the patronymic "Dracula" would literally mean "son of the dragon", dracul) and famous defender of Orthodox Wallachia against Ottoman expansionism, as well as infamous for its brutality perpetrated in battle [12]. In fact, a link between the real Prince Vlad and the Earl of Stoker had already been brought to the screen by the Turkish film Dracula in Istanbul (Dracula Istanbulda, 1952) by Mehmt Muhtar, as well as mentioned in Dracula television with Jack Palance in the role of the Vampire, shot by Dan Curtis in 1973 and written by the great Richard Matheson, one of the greatest authors of contemporary terror fiction. But even in this case, Coppola's film seeks a certain "realism": on the cruel exploits of war, and also on the physical features of Vlad III (of which a famous XNUMXth century portrait preserved at Schloss Ambras near Innsbruck has survived) is actually modeled after the Dracula played by Gary Oldman; an important detail, even considering that a fundamental trait of Stoker's character has been changed. In fact, unlike the count Dracula of the novel, and obviously of all those brought to the screen, the undead in Coppola's film is for the first time "promoted" to the rank of prince, which actually was the true Dracula from which the Irish writer drew inspiration, albeit with evident and significant differences [13].

However short, the sequences of the brutal clash between Vlad's army against the Ottomans, immersed in a blood-red sunset, seem to recall the epic style of Akira Kurosawa's great historical films, such as Kagemusha e Ran (but also a sort of nightmare version of the battle between the Russians and the Teutonic Knights in Alexander Nevsky by Eisenstein); the dark but particularly intense colors are perfect for the medieval setting of the prologue of the story, dominated by the figure of Vlad Dracula, leader and defender of the Cross, and his royal wife, Princess Elisabetha played by Wynona Rider herself who will return to the scene soon after (with a gap of about four hundred years, since we find her in Victorian London) in the part of Mina Murray, next to marry the young real estate agent Jonathan Harker. In this background of which there is no trace in the novel, being an original contribution of Hart's script, the character of Elisabetha, of which Mina will be the future reincarnation, is indirectly responsible for the transformation of Dracula from mortal to malefic undead: due to a deception perpetrated by the Turks, in fact, the princess will believe her husband has fallen in battle and will choose suicide. Vlad, furious and deeply wounded by what he interprets as an injustice on the part of the inscrutable divine designs, in a somewhat bloody and "blasphemous" scene will vow to the infernal powers, becoming the Vampire par excellence.

Once the setting moves to London (where, even only in the studio of Harker's boss, it already seems to breathe the gothic air of the Hammer Films classics ...), all the main characters of the novel find themselves on the screen: Mina, her friend Lucy Westenra and her suitors Arthur Holmwood, Texan Quincey P. Morris and Dr. Jack Seward. The latter is the director of the psychiatric clinic in the Carfax neighborhood, who follows the case of Mr. Renfield (the unfortunate predecessor of Harker who returns from crazy Transylvania, zoophagous and enslaved to the Vampire, and who we find here in the disruptive interpretation of the singer-songwriter Tom Waits ) and who will call on the scene Professor Abraham Van Helsing, played by a champion actor like Anthony Hopkins.

Also evident are the stylistic tributes to one of the greatest Italian masters of film horror, Mario Bava [14]. In fact, not only the majestic main theme of the soundtrack, the work of the Polish composer Wojciech Kilar, is somewhat reminiscent of the one written by Roberto Nicolosi for the legendary The Mask of the Devil (Bava's debut film from 1960, vaguely inspired by the story The Vij by Nikolaj Gogol and dedicated to a vampirism story set in Eastern Europe), but it is the same architectural and "furnishing" style of the rooms of the castle and the abbey of Carfax which evokes Gothic masterpieces such as Operation Fear e The three faces of fear. Indeed, in the scene set in the dining room, in which Oldman and Reeves reinterpret a famous moment from the novel, then re-proposed both in Nosferatu in that Dracula with Lugosi (hence the historic line «I never drink ... wine!»), There is a massive statue in a dimly lit corner which, at a careful glance, seems to reproduce the features of Baron Javutic, the vampire-sorcerer played by Arturo Dominici in Mask of the Demon...

As for the demanding characterization of the protagonist, it is undeniable that the intensity and flexibility with which Gary Oldman "becomes" Dracula are still palpable today; not coincidentally, the English actor, at the time thirty-four, got the part despite the production having considered more famous names such as those of Johnny Depp and Daniel Day-Lewis. Coppola's choice is remarkable who, to make it more plausible, made entire dialogues run in Romanian, and throughout the film Oldman speaks English with an Eastern European accent and a suggestive baritone stamp (worthily voiced in the Italian version by Dario Penne) . As Maurizio Colombo and Stefano Marzorati noted at the release of the film, Oldman's painful and at times almost "gigionesque" acting succeeds in rendering «the complex personality of Dracula: barbaric heroism, magnetic charm, perverse sensuality, secular loneliness, desperate love and even the original humanity buried in the monster's body " [15].

VAMPIRIC METAMORPHOSIS

A pearl of modern cinema horror it is also the whole part of the film dedicated to the vampirization process of Lucy Westenra, who becomes Dracula's first victim on English soil, coherently with what happens in the novel and, in principle, in the previous films. As mentioned, Mina Harker's best friend, for whom Stoker chose a symbolic and evocative name (which actually sounds like "Light of the West", threatened by the dark forces of the Vampire from "wild" Eastern Europe), is at the center of the attention of the three characters of Holmwood, Morris and Seward, for the first time all present in a film version and worthily characterized. The character of Lucy, played by London actress Sadie Frost, demonstrates a voracious and even promiscuous sexual charge, very little inhibited by the conventions of the Victorian label: this is evident in the largely flirtatious attitude towards the three "boyfriends", in the interest of The Thousand and One Nights edited by Francis Burton (the first historical English edition) illustrated with images closer to those of Kamasutra, and in a very quick hint of bisexuality with Mina. A first important variation from the novel and the others Dracula cinematic is the gruesome scene of intercourse outside between Lucy and Dracula in the form of a werewolf, after which the girl will remain under his evil influence, wasting away visibly and developing more and more evident vampiric traits, while in Stoker's book the Count "possesses" her by entering his room in the form of a bat (as also seen in the version with Bela Lugosi, in a scene readily faded to black as Dracula bends over Lucy lying in bed) [16].

Lucy, once fallen prey to the possession of Dracula whose mark is revealed by the typical, small marks on her throat, alternates states of insane sexual arousal with outbursts of hysterical fury, until the final visit of the Vampire that will take her to the grave: an event that in the novel we find at the end of the eleventh chapter, and which sees in the room the presence of the girl's mother, completely absent in the film and replaced in this scene with Arthur Holmwood (stunned by alcohol and then stunned by Dracula in the form of a wolf) . The one presented by Lucy is a "vampiric symptomatology", and therefore also demonic, which is clearly affected by the cinematic lesson ofExorcist by William Friedkin, including the gush of blood that the vampire vomits on Van Helsing in the act of pushing her back into the tomb, before ending her undead state with the help of Arthur Holmwood and the other gentlemen (again, consistent with the original story).

Even the clash with Lucy-vampira, in fact, basically follows the original story, and the reconstruction of the Westenra family crypt conveys an authentic sense of cold darkness: it almost seems to perceive the coldness of the marble and glass tomb, obviously found empty by Van Helsing and Lucy's three admirers. The appearance of the undead in a white funeral robe, busy dragging with her a small victim promptly rescued by the intervention of the protagonists, suggests that Lucy has become a lamia or a groove, a type of vampire who tend to attack especially children (respectively, according to the Greco-Roman and Jewish traditions) [17]. Furthermore Anthony Hopkins, with his expressive power, gives life to a very energetic and histrionic Van Helsing compared to the "classic" interpretations of the character by Edward Von Sloan (in Dracula by Browning) and by Peter Cushing (in Terence Fisher's) who, however intense, brought colder and more controlled Van Helsing to the screen.

As it was said, in the act of vampirizing the young victims, Dracula manifests his supernatural polymorphism abilities. If he transforms himself into a werewolf to undermine Lucy, when he is attacked by the heroic protagonists while he is in intimacy with Mina he indulges in other famous "versions" of his character: bench of greenish sepulchral fog, then monstrous and huge bat with diabolical features, for finally split into a frenzied mass of mice (citing the novel, but also Nosferatu and Dracula by Browning, films in which rats actually play an important stage presence). If the rat is associated with the idea of corruption and pestilence, the bat and the wolf are symbols par excellence of the nocturnal forces, and therefore linked to the symbolism of vampirism in various ancient European traditions. For example, these are the typical feral appearances that the priculics, a vampire mentioned in Wallachian folklore (which Stoker studied for writing the novel), while another particular type of vampire from Russian traditions called mjertovjek he is the son of a werewolf and a witch [18].

DRACULA AND THE WOLF

Coppola's Dracula, thus recovering an important tradition of vampire folklore or their, so to speak, "consanguinity" with werewolves, denotes a close familiarity with the "children of the night" who howl at the moon. Also interesting is the confidence with which Prince Vlad calms the albino wolf that assails the sideshow of the cinema, saving Mina of her from her jaws: a "shaman" Dracula, also given his possibility of assuming the likeness of the animal [19]?

An important detail is also linked to the symbolism of the wolf that can be observed in the iconography of the original poster of the film (which, at the time, very much struck the attention of the writer, noting it affixed to the entrance of the city cinemas ...), which takes us directly back to great literature and traditional symbolism. Above the central foreground in a black and white bruise that recalls the nineteenth-century photograph, of the Mephistophelic Oldman-Dracula holding a lifeless Wynona Rider-Mina in his arms, we see a monstrous and snarling vampire face surrounded by two heads of wolf. The reference seems, of course, to the two main animal forms that Dracula assumes for his nocturnal raids; but, upon closer inspection, the central vampire bat would reveal almost lion traits. If we consider the particular position of the two lateral wolves, the image that comes to mind is the one found in a passage of the Saturnalia of Macrobius. In the work in question, an encyclopedic treated in the form of a dialogue on Roman traditions, the author of the fifth century in fact tells of a three-faced sculpture, once located in the temple of Serapis in Alexandria in Egypt: the central head, the lion, represented the present time and what we know; the lateral wolf heads, on the other hand, meant two forms of the unknown, past and future: what concerns the most remote past times, and therefore has been forgotten, and what, as far as to come, has not yet you know [20]. Even only on the advertising poster of the film, therefore, the esoteric values of the figure of the wolf, and therefore of that of the Vampire, are explicitly called into question.

REFERENCES AND QUOTES TO OTHER WORKS

From here we can connect to the particularly significant and "tasty" (as much as a rare steak, of course) cultural references scattered throughout the scenes of the film: for example the abbey of Carfax, near which Dracula will settle in his British trip, looks like the one portrayed by the painter-symbol of German Romanticism, Caspar David Friedrich, in his famous Abbey in the oak wood (1810); and during dinner at Dracula Castle, Harker notices a painting of Prince Vlad hanging on the wall (obviously mistaking it for that of an ancestor), which is nothing but an explicit homage to the famous Self-portrait with fur by Albrecht Dürer, painted by the German master in 1500. It is also remarkable how the skimpy dresses of Dracula's brides and the death robes of Lucy Westenra are reminiscent of the female characters designed by Alphonse Mucha, and that on various other costumes (all the work of the Japanese designer Eiko Ishioka, including the picturesque vestments of Dracula ) as well as on the interior scenography the atmosphere of the darkest masterpieces of Gustav Klimt, Aubrey Beardsley and Gustave Moreau seems to hover.

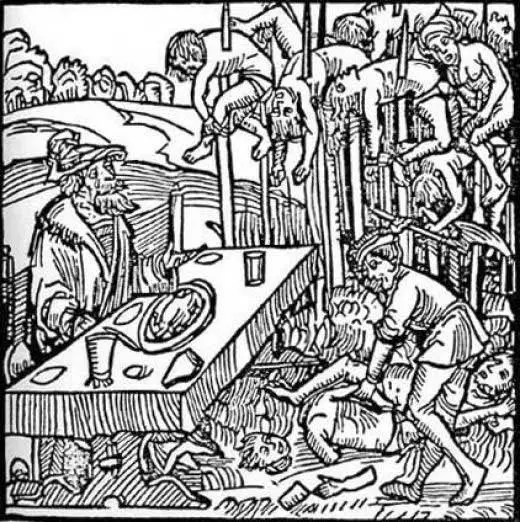

Van Helsing, leafing through the pages of a Book of Vampires (yet another quote from Murnau and Dreyer), stumbles upon some particular woodcuts: the first is a portrait of Vlad III, probably inspired by Povest'o Drakule, Russian chronicle of uncertain attribution drawn up at the end of the XNUMXth century mainly focused on macabre anecdotes relating to the history of the prince, which can be admired in the subsequent overview of Vlad having lunch among the impaled corpses (another historically documented image); the third image, which would portray the suicide of Princess Elisabetha, instead reproduces an illustration taken from one of the first editions of the novel, probably the stormy nocturnal encounter between Dracula and Mina in the latter's bedroom.

In another blatant and pleased homage to the unforgettable author of Draculafinally, if one observes carefully in the scene of the meeting in London between Mina and Vlad (whose walk, it should be noted, is filmed in the 18 frames per second of silent cinema, and in fact the newborn cinema is the destination of the first meeting between the young lady and the Vampire) there is a "sign man" announcing a representation ofHamlet at the Lyceum Theater, played by none other than Henry Irving: it is obviously the theater directed for years by Bram Stoker, personal secretary of the great and charismatic English actor whose figure, together with that of Vlad Ţepeş, was the basis of the inspiration for the Literary Dracula. A detail that must not have particularly cheered Irving, who, as far as we know, did not show the slightest appreciation for his pupil's novel ...

As for another fundamental idea of the plot mentioned above, the theme of the female protagonist as the reincarnation of the deceased bride of Dracula actually comes from the aforementioned television film by Dan Curtis, even if in that case the character in question is not it was Mina but Lucy. The theme of "previous lives", metapsychic phenomena in general and the various related practices (hypnosis, mesmerism, mediumistic sessions ...) were notoriously very familiar topics to late nineteenth-century English society, as well as the famous magical-occult circles such as the Theosophical Society and the Golden Dawn, environments that Stoker perhaps frequented but, it seems, without actually adhering to them seriously [21]. In the novel it is the character of Van Helsing, as a scholar of the occult and vampirism, who introduces the theme of paranormal phenomena and extrasensory perceptions, after evaluating Lucy's disturbing symptoms. The psychic bond that Mina develops with Dracula after the vampire-intercourse (in the film, a long scene of erotic-bloody effusions between an athletic shirtless Oldman and an objectively gorgeous Wynona Rider in undressed) is in fact fundamental, for the group of protagonists devoted to the elimination of the vampire, in order to follow in the footsteps of Dracula fleeing in Transylvania. It is at the castle, in fact, that the final battle will take place, which, moreover, will cost the life of Quincey Morris (following the novel correctly); however, Mina takes care of the elimination of the vampire, “closing the circle” in the same place where, centuries earlier, Elisabetha had died and Prince Vlad had chosen the path of vampirism (and here we depart again from the original story).

CONCLUSION

In light of all that has been examined, Coppola's film therefore has its strength in being able, so to speak, to amalgamate love, art and vampirism in an original way, three conditions that allow the human being to free himself from own transient condition [22]. In conclusion, we can once again take note of the now historical importance of a film like Bram Stoker's Dracula, with all the "strengths and weaknesses" of the case. By way of an almost paradoxical anecdote, it is curious that among the detractors of the film, or rather, among those who meticulously maintain a fidelity to the novel not fully respected even in this case, there was really ... the Count himself, or Sir Christopher Lee, an authentic monument of fantastic cinema and the only performer historically able to contend with Bela Lugosi for the name of “classic” Dracula by definition. On one occasion, in fact, the great Italian-English actor was critical in this sense about Coppola's film [23]. In any case, looking at it still today after thirty years, it is undeniable that Bram Stoker's Dracula has managed worthily to preserve and renew one of the most archetypal and multifaceted figures of the modern Fantastic, as well as to restore due importance to the name of the creator of that figure [24].

Note:

[1] Massimo Introvigne, The lineage of Dracula. Investigation of vampirism from antiquity to the present day, Mondadori, Milan 1997, p.347.

[2] Maurizio Colombo, Stefano Marzorati, Bram Stoker's Draculain Dylan Dog presents: Almanac of Fear, Sergio Bonelli Editore, Milan 1993, p.28.

[3] Cf. Dracula bloodlines: the man, the monster, the myth, documentary contained in the DVD of Dracula by Bram Stoker by Francis Ford Coppola, Columbia Pictures, 2006.

[4] Cf. Road to Dracula, documentary contained in the DVD of Dracula by Tod Browning, Universal, 2004.

[5] Cf. Dracula bloodlines: the man, the monster, the myth, cit.

[6] Massimo Introvigne, The lineage of Dracula, cit., p.317.

[7] Pier Giorgio Tone, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. Il beaver cinema n.36, The new Italy, Florence 1976, p.33-34.

[8] Matei Cazacu, Dracula. The true story of Vlad III the Impaler, Mondadori, Milan 2006, p.250.

[9] Cf. Road to Dracula, cit.

[10] Cf. Dracula bloodlines: the man, the monster, the myth, cit.

[11] Mauro Gervasini, Love at the first bite. The golden age of Dracula, in Emanuela Martini, edited by, AA.VV., From Caligari to zombies. Classic horror 1919-1969, Il beaver, Milan 2019, p.62.

[12] On Vlad Țepeș, cf. Raymond McNally, Radu Florescu, Looking for Dracula, Sugar, Milan 1972; Matei Cazacu, Dracula. The true story of Vlad III the Impaler, cit .; Gianfranco Giraudo, Drakula. Contributions to the history of political ideas in Eastern Europe at the turn of the fifteenth century, Ca 'Foscari, Venice 1972.

[13] It should be borne in mind, in fact, that the figure of Vlad Țepeș, despite the known turpitudes performed on his enemies (and sometimes towards his own subjects) that fueled his "macabre legend", over the centuries was never associated with vampire mythology (see Massimo Introvigne, The lineage of Dracula, cit., p.207-208), of which Stoker's Dracula has become the symbol par excellence. Not only that: his dominion extended precisely over Wallachia, never over Transylvania. Stoker preferred the name of this last historical region of Romania, judging it more musical and evocative (the "land beyond the forest") to set the origins and deeds of a character like "his of him" Dracula (ndA).

[14] See Alain Silver, James Ursini, The vampire film. From Nosferatu to Bram Stoker's Dracula, Limelight, New York 1994.

[15] Maurizio Colombo, Stefano Marzorati, Bram Stoker's Draculain Dylan Dog presents: Almanac of Fear, cit., p.30.

[16] A scene which, moreover, would recall a passage from Varney the Vampire, a river novel of about 860 pages (!) written by Thomas Preskett Prest and John Malcolm Rymer and published in installments, the first of which came out in 1847. (ndA). See Massimo Introvigne, The lineage of Dracula, cit.

[17] See Gianni Pilo, Sebastiano Fusco, The Vampire, introduction to AA.VV., Vampire stories, Newton & Compton, Rome 1994; Rossella Bernascone, Introduction to Bram Stoker, Dracula, The Repubblica library, Rome 2004, p. VIII.

[18] Gianni Pilo, Sebastiano Fusco, op.cit., P.11.

[19] See Mircea Eliade, Shamanism and the techniques of ecstasy, Mediterranee, Rome 1974; about the lycanthropy linked to the shamanic and warrior context in the Slavic traditions, cf. The Song of Igor's hosts, edited by Eridano Bazzarelli, Milan, Rizzoli 2000.

[20] On the passage of Macrobius, and on the complex valences of the archetype of the wolf as a symbol of darkness but also a bearer of light and knowledge (think of the wolf sacred to Apollo, or the wolves Geri and Freki who sit next to the throne of Odin), cf. Gianni Pilo, Sebastiano Fusco, Introduction to AA.VV., Stories of werewolves, Newton & Compton, Rome 1994.

[21] Massimo Introvigne, The lineage of Dracula, cit., p.229-230.

[22] Paul Duncan, Jürgen Muller, edited by, AA.VV., Horror cinema. The best horror movies of all time, Taschen, Cologne 2017, p. 221.

[23] Paolo Zelati, That monster Lee. in Horror Mania 29, December 2006, p.32-33.

[24] In fact, apart from the notoriety it has always enjoyed among admirers and scholars of the Fantastic, Bram Stoker's fictional production and his very name were for much of the twentieth century overshadowed by the cumbersome fame of the vampire born of his imagination. A similar case is that of Arthur Conan Doyle, actually less famous to the "general public" than the very popular figure of Sherlock Holmes, and in some ways this also happened with regard to Howard Phillips Lovecraft and his "Myths of Cthulhu" (ndA) .