On Austin Osman Spare's (neglected) influence on Surrealism — meaning surrealism not only as an artistic dynamic, but as a magical praxis.

di Andrea Venanzoni

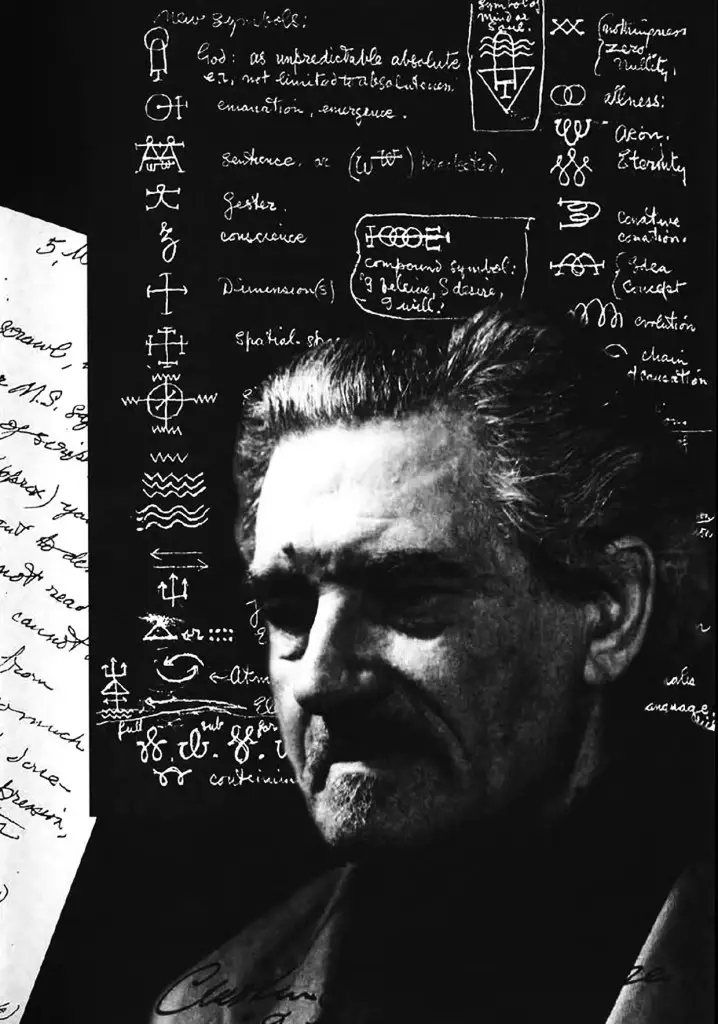

There must be very few people interested in art these days in London who do not know the name of Austin Osman Spare.

The Art Journal, 1907

Darken your abode, close the door, empty your mind. Even so you are in good company.

Austin Osman Spare, The Logomachy of Zos

The Great Absent:

how surrealism removed Austin Osman Spare

Between April and September 2022, the suggestive setting of Venice, with its decadent and shady languors, hosted an exhibition with a very significant title: 'Surrealism and magic – the enchanted modernity'. Scrolling through the vast exposition, it is evident how the phenomenology of the magical roots of surrealism is seen in the ghost of a counter-cultural reaction directed against the prevailing positivism and scientism at the time: and it is a fact that Paris, the cradle of nineteenth-century rationalism, like London and Berlin in the same years, met a powerful man between the XNUMXth and early XNUMXth centuries Revival magical and esoteric that would have influenced (also) the artistic production.

The Belle Epoque of esotericism – magicians, sorcerers and alchemists in fin de siècle Paris [1], this is the title of a volume that collects and organizes some writings and characters active in the French capital precisely in the field of occultism in that same period of time. And how to forget The magician, famous novel by WS Maugham, inspired by the human and intellectual events of Aleister Crowley and set, not by chance, in Paris?

In 1924, in the (first) Surrealist poster, in a small chapter emblematically titled 'Secrets of the Surrealist Magical Art', André Breton effectively summarized the magical-operative methodology of the newborn artistic movement, writing:

have something brought to you to write, having settled in a place which is as conducive as possible to the concentration of your mind on itself. Put yourself in as passive or receptive state as possible. Ignore your genius, your own talents and everyone else's. Tell yourself that literature is one of the saddest paths that lead to everything. Write quickly without a preconceived topic, fast enough that you don't hold back and aren't tempted to re-read yourself. The first sentence will come by itself, because it is true that every second there is a foreign sentence that only asks to be externalized [...] Continue as much as you like. Trust the inexhaustible nature of the murmur.

[2]

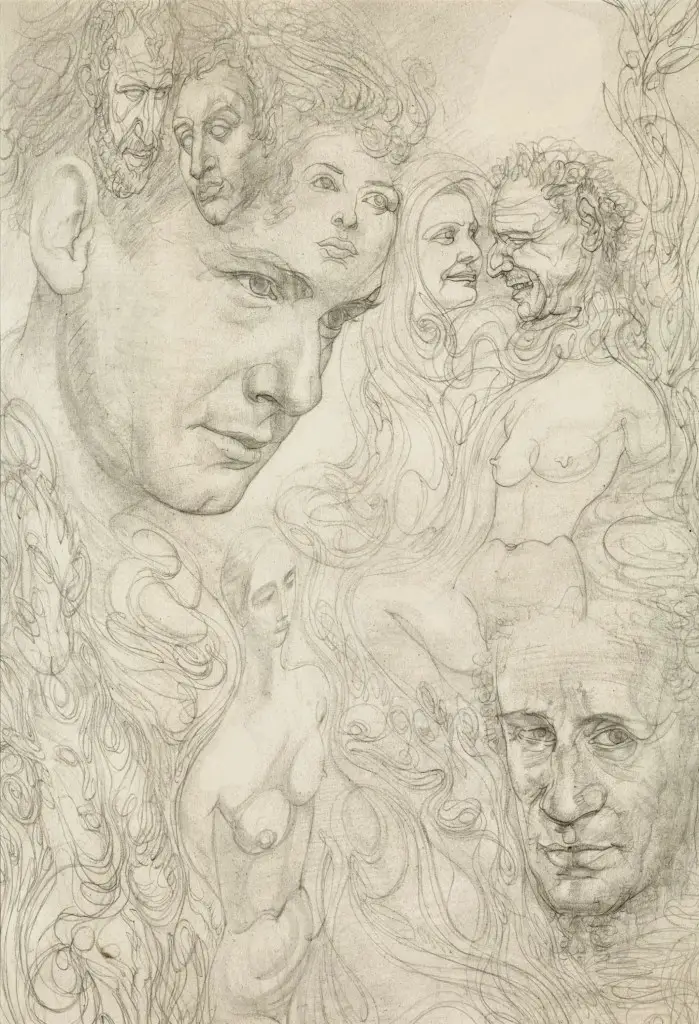

Overcoming the superstructural retention of consciousness, reaching an ataraxic void within which to shape a form of unconscious absolute will, an act-without-acting similar to Wu Wei of the Tao, the technical-shamanic modeling of automatic writing and painting as the purest flow of an ego chained for too long, and now instead wild, atavistic, evoked from the depths of the inner abyss.

Anyone familiar with the work and thought of Austin Osman Spare, will have found more than a few episodic similarities in that passage from Breton. Precisely for this reason, Spare's is a deafening, deafening absence in the heart of the Venetian exhibition. An absence, it must be said, which has been painfully protracted for some time and which has expunged Spare in the historical-philological reconstruction of the artistic and conceptual influences exerted on the paraphernalia surreal.

The most purely esoteric figures present in the heart of the Venetian exhibition were undoubtedly that of Kurt Seligmann and the equally important one of Leonora Carrington. The first is historically considered an authentic link between surrealism and occultism: a pictorial surrealist of Swiss origins, he was also a historian of the occult, with a significant history of magic to his credit [3], appreciable when the reconstructive attention is focused on France and on the interweaving of art and magical thinking, but more hasty when the attention is focused on other countries. As for the Carrington, as was underlined in a recent London exhibition and in the related, highly documented catalogue [4], would have practiced ancient witchcraft rituals in isolated and remote areas of Mexico, together with the artist Remedios Varo.

And it is truly bizarre that they were included in the exhibition Surrealists who were also, really, occultists, having then to register the exclusion of those who, like AOS, were really the total link between these two worlds, and well before purchasing, of surrealism itself.

The Golden Hind:

la vexed question of influences

Surrealism not only as an artistic dynamic, but as a magical practice. It is this idea that more than any other vividly connects Spare and Surrealism. After all, the clear dissatisfaction of the surrealists with the world and its gloomy, bureaucratic reality would have pushed French artists to consider their creations no longer as mere forms of expression of the creative spirit but as an authentic spell of psychic transformation.

Anyone who has read the Bretonnian passage quoted above with even a superficial dose of attention will have realized the organic and non-trivial assonance with many of the Sparenian precepts [5]. The reason why Spare is to be considered a pivotal figure of artistic surrealism it is precisely for this reason rather self-evident, although this reason is neglected and often overlooked. We will first focus on the functional and structural importance of Spare's concepts and works and how they were intrinsically surrealist [6], and subsequently on the reason for this removal.

First, the chronological-historical argument. When Breton composed and published the first Manifesto, Spare had already printed some of his essential works. The Surrealist poster it is in fact from 1924, while some of Spare's most significant works precede him by many years: Earth Hell is from 1905, the Book of Pleasure 1913 and The Focus of Life of 1921. Irony of synchronic semantics, the subtitle of this latest work is 'The murmurs of AOS', is exactly I murmured is the final keyword of the Breton passage we have quoted supra.

Not only that: Spare, well before the emergence of surrealism, had already exhibited in prestigious galleries and had been lauded by the cultural world as a promise, and in some cases even defined as 'genius'. In fact, Spare's art was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1904, when the artist had not yet turned eighteen [7]; the Royal Academy represented for the British artistic world the Gotha absolute, the point of arrival that many artists with established careers could not even have hoped to reach in an entire existence.

Precisely for this reason, the judgment of genius on Spare formulated by the President of the Academy, John singer sargent [8], does not appear excessive or plastically laudatory, but purely factual. On the other hand, the initially general appreciation for Spare's pictorial and artistic achievements involved a large number of qualified public. Sargent's judgment was in fact echoed by the well-known and influential painter John Augustus [9].

There was no lack of fierce criticism, above all of a moral nature and which focused on the aesthetics and conceptual substance of Spare's works. There is no doubt however that, beyond some not entirely commendable judgments expressed by the world of art criticism, however never linked to technique and ability but always to the concepts resulting from the works, the name of Spare had in that arc wide circulation thunderstorm.

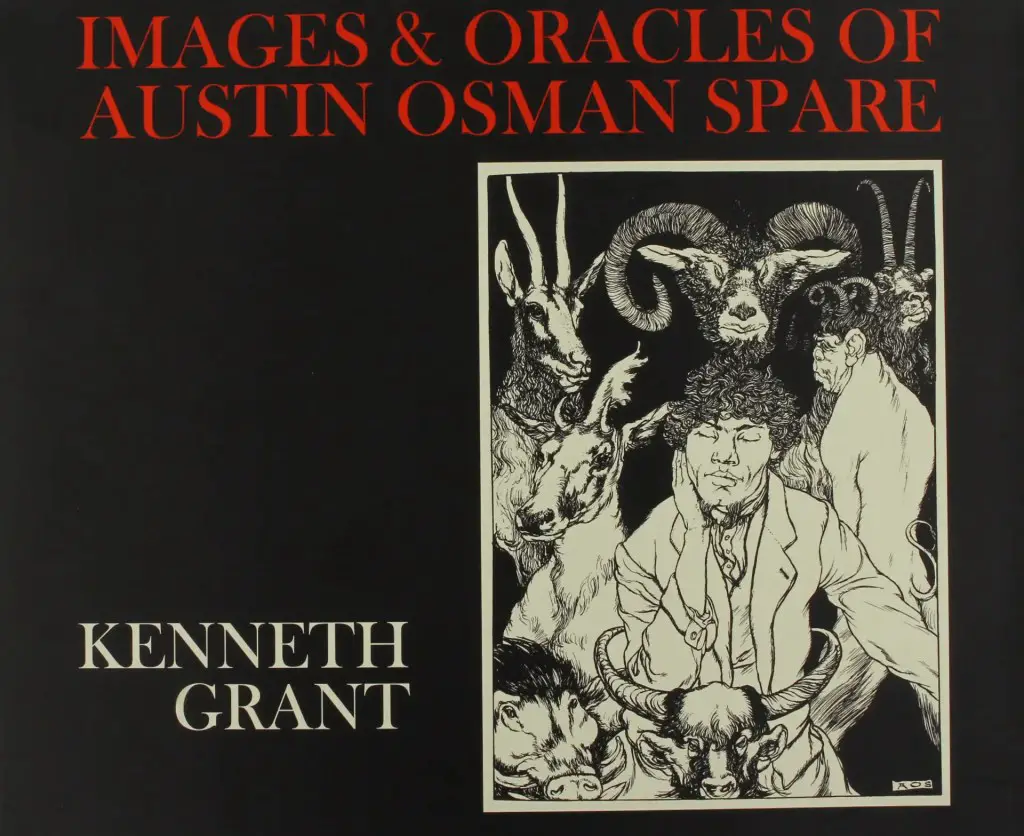

On the other hand, Spare cannot be dismissed as a dungeon maverick practically unknown in the cultural world, we are witnessed by the objective fact that one of the literary and artistic projects of which Spare was co-editor, The Golden Hind, saw the collaboration of names such as those of Aldous Huxley and Havelock Ellis. In this context, the veracity of the assertion reported by appears to matter little Kenneth grant according to which George Bernard Shaw would have stated that:

Austin Osman Spare's medicine is too strong for the average man.

[10]

Indeed, there is no doubt that, for better or for worse, Spare's name circulated in galleries, newspapers and academies, and that it equally fascinated and scandalized. He was certainly not an author for the taste of the masses [11], but that did not imply that his name was underground or the preserve of small elites. One of the historical moments of maximum popularity of Spareian artistic works can be temporally located between 1911 and 1916, through collaborations with magazines like Form o The Yellow Book. As evidence of this assertion, it can be noted that in those years on the Book Lovers Magazine with an article by Ralph Straus, Spare's name was recognized as one that had achieved widespread popularity [12].

It is doubtful, as we will see, that AOS could have been seriously interested in being recognized as the noble father of some avant-garde art movement, nor did he do anything during his lifetime to boast the theoretical credits of an abstract birthright. The only ones 'institutional' traces of references to the surrealism associated with Spare, are predominantly ironic or, positively, interested. The first category includes the ironic references that Spare himself made while conversing with friends or sending notes to his circle of admirers or correspondents, ironically bearing the appellation of 'surrealist'. On the other hand, the second includes those episodes that mentors and enthusiasts of the Snow Hill painter elaborated to make Spare known and celebrated even more, exploiting the rising wave of the popularity of surrealism.

In terms of influences, there is no direct documentary evidence that Breton may have come across Spare's works. It is certain, documentally, however the deep interest nurtured by the Surrealists for occultism and the idea, cultivated by Breton, of a relational network between operators of the occult and magical traditions [13]. In this context, considering that the main works of Spare are located well before the emergence of the surrealist movement, it could be the hypothesis that some of the surrealists came across the works and concepts of AOS, precisely by virtue of the relational networks between magical groups .

On the other hand, and on the other hand, it could be noted that the Surrealists have always been ready to bring out their real or presumed conceptual antecedents: both the (first) The Manifest how much theAnthology of black humour they contain articulated lists of artists, writers and personalities definable as surrealists before surrealism. Precisely for this reason it could be argued that it would have made little sense to omit Spare's name from the list of conceptual influences. We will discuss how this peculiar objection has no foundation at all later, suffice it to say here for now that the point is not so much or not only the direct knowledge that the French Surrealists may have had of the young English painter, and of his conceptual theories, as much as the almost total absence of the connection between Spare and the cultural foundations of surrealism that we find in the criticism next one to the explosion of the surrealist phenomenon.

The fact therefore, in other words, that very few in the history of art and art criticism have the idea of organically investigating the assonance of themes, concepts, works between Surrealism and AOS and the influences in power exercised by the latter on the avant-garde movement.

Borough (Surreal) Satyr:

surrealism in London between Dalì and Spare

Naturally, it could also be objected that the circulation of Spare's more purely theoretical-literary works was rather limited and, by the parameters of the time, also rather unwelcome: the critics in fact did not understand Spare's theories and began, after the first ones, cited , enthusiasm for pictorial works, to question, morally, even the nature and matrix of representations of hybrids, monstrous entities and allegories with a profound erotic-mystical effect.

However, even if it was bad publicity, it was still publicity. And moral outrage, indeed, could have been a powerful magnet for the interest of the surrealists, for whom the scandal was also method. The oblivion that would have seized Spare would have been later, chronologically located in years in which the influence on surrealism could already have been abundantly exercised.

Furthermore, surrealism arrived in London only in 1936, between June and July with a show at Burlington Galleries; known to the intellectual circuits, but decidedly less to the vast audience of Aficionados of representational art, the French artistic movement soon conquered the front pages of English newspapers, thanks to the monumental interest of visitors for the exhibitions staged.

In the present case, the wider success smiled on the works and on the figure of Salvador Dali who, enthusiastic about the reception received, declared during a public reading that surrealism in London was taking root in a profound and brilliant way, stripping and resurrecting the psychic and atavistic connection with the British spiritual artistic tradition, such as that of Lewis Carroll, Jonathan Swift, the Pre-Raphaelites.

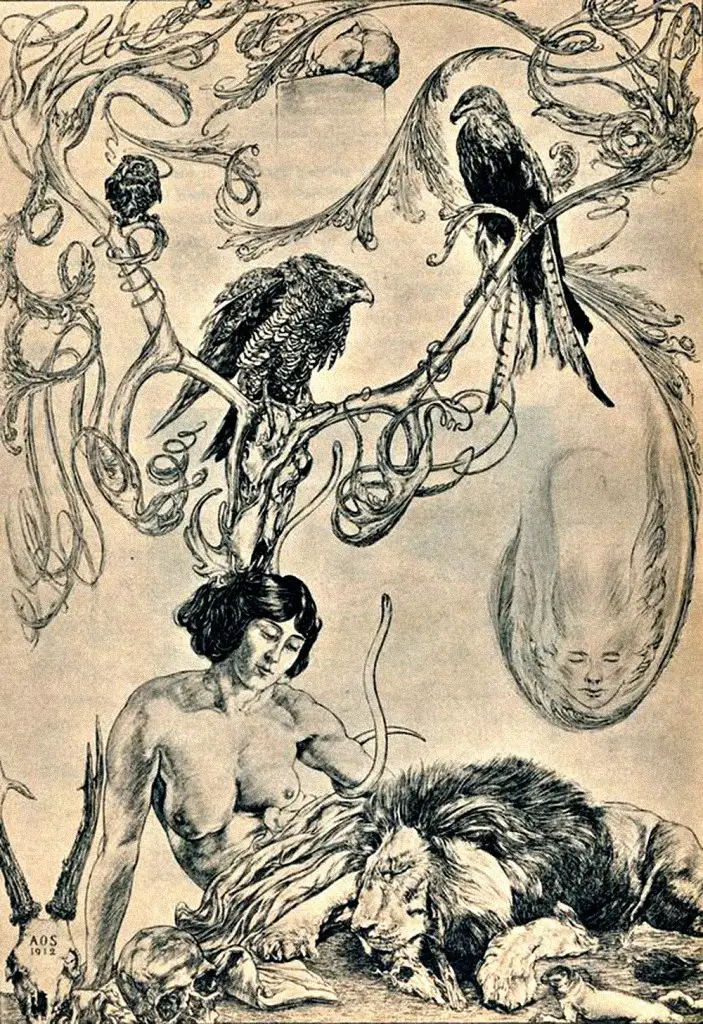

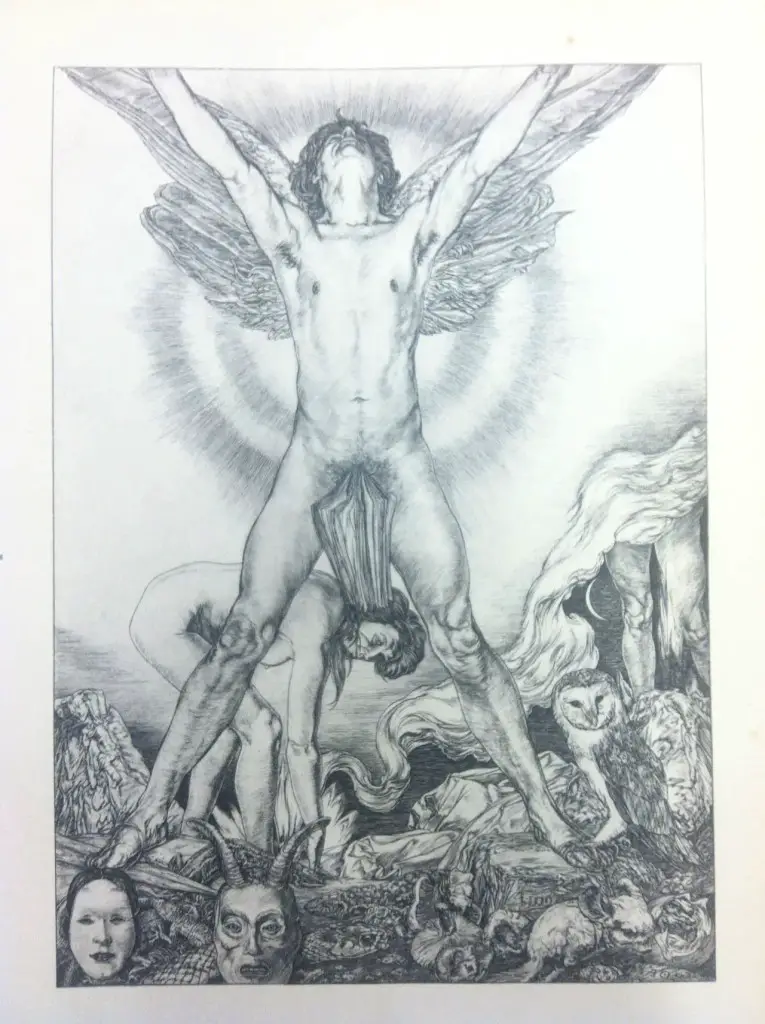

Dalì's sentence, like the one penned by Breton, presents a practically total adherence to another canon formulated by Austin Osman Spare, that of resurgent atavisms [14]. The spirit of authentic cartographer of the human psyche, of post-shaman, which distinguished Spare, according to what Gavin Semple underlines, has been sublimated in the purest form of a connection with the emergence of creative and artistic genius [15]: the psychic assemblage of animal forms, the vitalization of the feral energy drawn from the relationship between the human and a profound psychic immersed in the black blanket of what we have been, really or potentially, have been achieved through the pictorial technique that has elaborated and assembled panoramas of bestialization of the psyche, in long choreographic sequences of animalistic, mythographic and demonic essences.

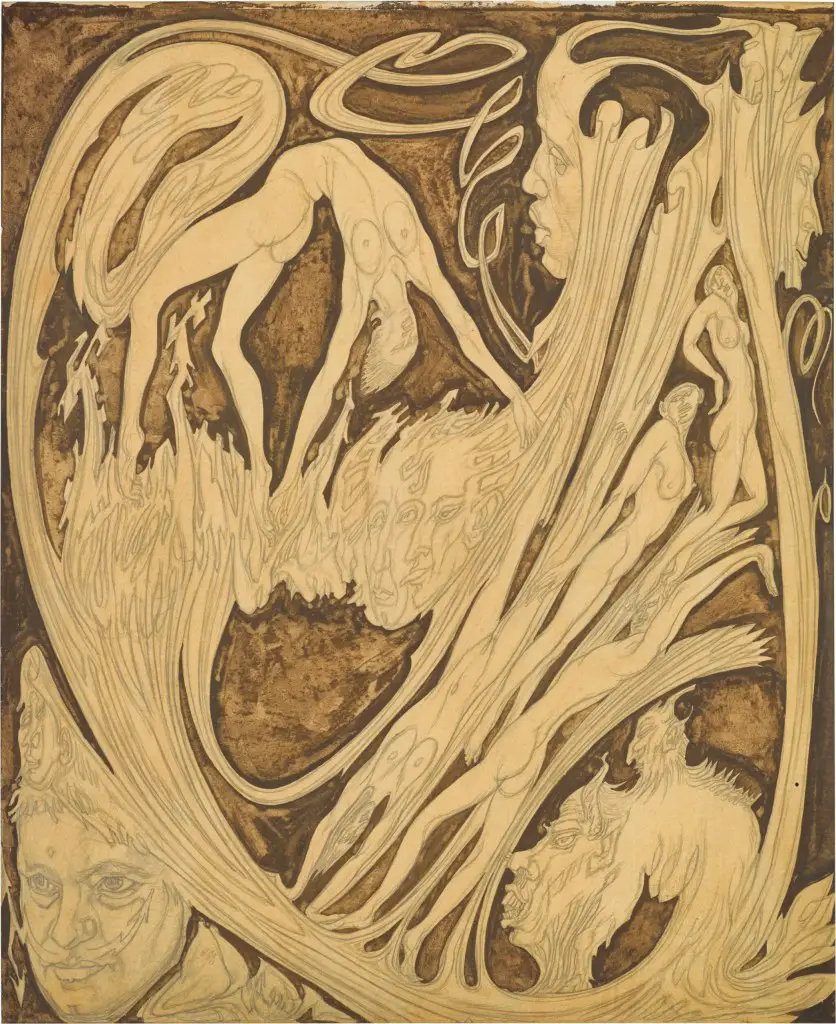

Lexicon and concepts marry in an organic, coherent way and it seems really strange to be able to think of a mere lexical coincidence between AOS and Dalì. To the same extent that the connection between Spareian's theories on automatism in writing and painting and what Breton and André Masson realized and theorized seems truly magical. The Focus of Life, which as we have seen precedes the emergence of the Surrealist movement by almost ten years, was written in a state of semi-trance [16]. Not only; the Spareian pictorial technique overcomes any hesitation and objection that Masson had formulated on the possibility of truly realizing an automatic painting. Remember the journalist and literary critic Hannen Swaffer:

on some occasions, to create automatic paintings, Mr. Spare fixes his gaze for a long time in a mirror inducing a state of self-hypnosis. In this hypnotic trance, he continues to paint for hours and then when he revives from hypnosis he finds pages and pages full of stupendous sketches and drawings.

[17]

According to Masson, the creation of a truly automatic painting would have been almost impossible, unlike automatic writing. The essential junction would have been represented by the psychological difference of the medium technician used [18]. Spare, on the contrary, demonstrated how the difference did not consist in the technical element, but in the medium personal. In other words, it was the individual, the magic operator, who evoked them and made them emerge in an artistic form by connecting with the darkest and most remote areas of his own subconscious. An operation that is neither simple nor linear and to which he should have dedicated himself, at the price of enormous sacrifices, your life, your success and your reputation. Which Spare did and which the Surrealists, on the contrary, were careful not to do.

It is here in fact the case to return to the question of the influences admitted by the Surrealists. Oswell Blakeston [19] he acknowledged that, apparently scientifically and conveniently, the Surrealists had kept Spare out of the picture of their alleged influences. And for a specific reason. For, Blakeston pointed out, Swift might be an inspiration for black and caustic humour, Lewis Carroll in the nonsense sector, in other words all vampirized influences in a single, relative, limited perspective, but Spare would be a threat to them, because they could not have appropriated it with impunity.

Spare had been a Surrealist among Surrealists long before Surrealism. And in fact by probing the conceptual and pictorial production of the Borough Satyr and comparing it with the creations of the surrealists, it is evident how Blakeston hits the mark. On the other hand, the same English public opinion for a certain period of time showed that Spare was a proto-surrealist.

"The Father of Surrealism is a proletarian”, triumphantly headlined the Daily Sketch of February 25, 1938, with a little pride cockney. In reality, reserved and kind-hearted as he was, Spare never particularly cared about the possible recognition of a birthright title in the Surrealist field and the use of the term he made was always very ironic [20], as in the romantic letters sent to Ada Pain, in which the painter signed himself

Your surrealist, Austin Spare.

[21]

Both Spare and Pain shared a passion for horse bets. There is an aside to open here: of course, what could possibly be esoteric about betting on a sporting horse race? This is not the direct practice of a sport, but a game of chance which at most could be based on knowledge of the conditions of the horses, the jockeys, the racing circuit, the weather conditions, and so on.

Actually, another great radical artistic experimenter, the father of Viennese Actionism Rudolf Schwarzkogler, was also a huge fan of horse racing [22] and bets, seeing in the shadows of that baleful obsession that leads many to financially ruin a gloomy and chthonic ritual: the mingling of an absolute will, obsessively focused in the flaming time span of the race itself, within which illusions, desires and in in which the object of one's will is no longer winning but self-referentially the mere participation in the act of betting, in a reiterated mantra circular that breaks down desire and that precisely with this makes it come true [23].

And the expression mantra is used pour cause; some delightful pages dedicated to horse racing indeed peep through the pages of the volume Aghora – to the left of God [24], dedicated to that peculiar form of radical tantrism which is the doctrine of the Aghori. On the other hand, the matrix of horse racing betting is inherently a oracular act, and precisely this aspect instills an enormous dose of dependence: the mind focused on the details and on the method for finding the potential winning horse overcomes the very idea of economic winnings and sublimates itself into something purely spiritual and erotic.

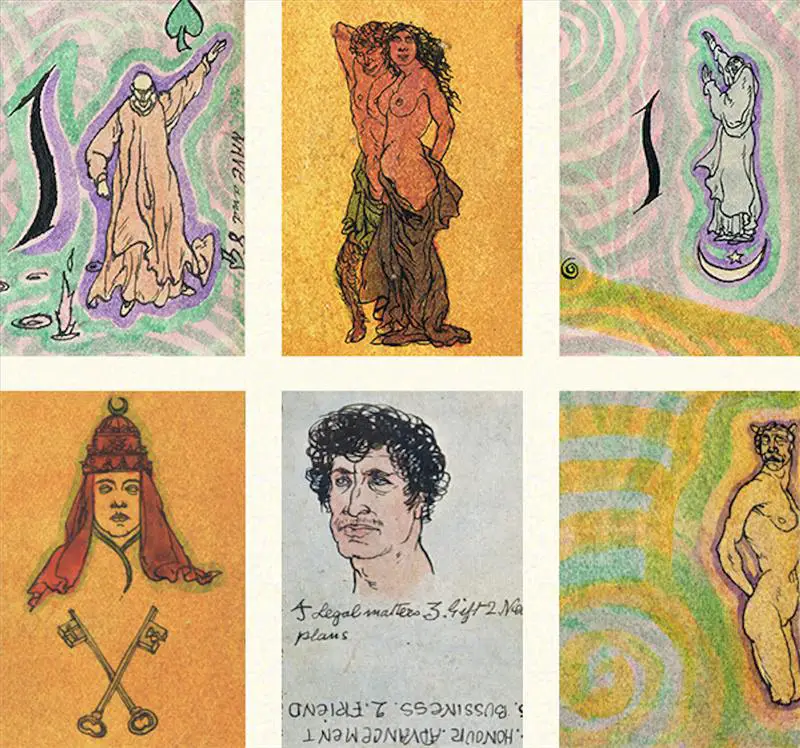

In the same year as the Dali exhibition in London, Spare held his own exhibition at the center of which were carte Obeah [25] made by him to divine the name of the winning horses at the London races. Of these cards there is also an announcement published in the London press with the very evocative title 'Unlucky at gambling?': the cards for this commercial occasion, sponsored by Dennis Bardens who helped Spare to commercialize them, were renamed 'Surrealist cards for horse racing predictions'.

The idea of devising a magical-artistic method to be successful in the game was clearly also typical of the Surrealists who, with Marcel Duchamp and its Monte Carlo roulette bond (1924) detailed a numerological-oracular way to win at casinos, specifically at roulette [26]. The Duchampian theoretical assumption of transforming roulette into a logical game like a game of chess presupposes a transmutation of the Ego very similar to that postulated by Spare: a clear deflagration of Freudian psychic subjectivity which leaves room for an alveolar inter-subjectivity within which the phenomenal reality of the will is shaped by connections and relational weaves.

And precisely the mystical-oracular effect leads to a further point of conjunction between surrealism and Spare: i tarot.

Tarot Deck: the cards of Zos

In 2017, a deck of Tarot cards painted one by one by Leonora Carrington was found in Mexico City; an exceptional discovery, honored by the luxurious publication in a box set and in a volume edited a short time later by Fulgur Press [27]. And Breton's interest in tarot cards is known, of which he, together with other surrealists, revisited it in the early years of the Second World War, replacing the mystical and medieval figures with topos literary works dear to Surrealism itself, and to which he would later dedicate the lyric poem Arcanum 17, written in the 1944.

Austin Osman Spare also had a deep predilection for cartomancy and for divination by means of the Tarot and like the Surrealists, but 34 years early, he replaced some of the classical figures with images from his vivid and intense esoteric imagery. On the other hand, the same reminiscences of the deep and intense relationship with Mrs. Paterson [28], who at a young age would have initiated him into the mysteries of witchcraft, were nourished by the purest essence of the divination of which Paterson would have been a practitioner. AOS used various divination techniques throughout its existence. One is the one mentioned supra. Another was a peculiar system of tarot cards, entirely personal, which had disappeared for a long time and which have recently been rediscovered and the object of a new publication [29].

The founding assumption of the Spareian theorization linked to the techniques of divination, reminiscent over the years of the post-Kantian theories of the German philosopher Hans Vaihinger whose thinking was introduced to Spare by Kenneth Grant after the end of World War II, is that of a ontological relativity of the phenomenal world. Already in Book of Pleasure this idea, translatable into a philosophy of 'As if', had been fully illustrated, but Spare will return to it in many other episodes and writings. The eradication of the retentions made by the conscience and by the rules provided by a given system represents the most perfected form of what Surrealism would have liked to represent but instead, for various reasons, it failed to be entirely.

According to Spare, the world is nothing but a flow of thought, and science itself is grossly mistaken by inverting the polarity of the responses to the formation of cause/reaction links: it is not the body, the nerves, the cells that produce thought, but it is thought itself to shape and modulate their own vehicles. This also explains the substantial difference between the limit observed by Masson and Spare's reduction of that same limit.

For Masson, at most there can be a suspension of consciousness during the creative act; for Spare, on the contrary, the flow of thought dominates and triumphs over a reality subjectively made theater of flesh and desires, to the point of infusing it with the weight of one's own vital breath emerging from the shady cavities of one's Ego. Spareian divination, like artistic creation, does not foresee but ground. Simply put: create your own reality, making it happen.

Sidereal: Spare's answer to surrealism?

A completely peculiar pictorial technique used by Spare, deeply connected to the relativized ontology of the world and of the sensible reality that was his own, was that of the Sideralism. Starting in the thirties, the English painter-magician began to focus his attention on iconography and on pop portraiture, focusing on portraits of famous Hollywood stars, actually becoming a historical-conceptual antecedent of pop-art and Andy Warhol: the technical peculiarity of these portraits, based on an anamorphic translation of the salient features of the morphology of the immortalized subject, is the dysmorphia of size and proportions, which are altered by stretching, compressing, distorted perspectives. The salient characterization of this technique is that the configuration of the pictorial result varies according to the observation angle adopted by the viewer.

It has been observed how Spare's anamorphic choice could have meant the full will to highlight an intrinsically magical aspect of the portrayed subject, an interiority that can only be observed by resorting to different perspectives [30]. However, this magical-critical reconstruction was rejected by who, how Frank Letchford [31], considers the sidereal-anamorphic experiments a modulation based on the relativity of the idea placed at the foundation of creation, rather than a direct connection with the Spareian magical theory.

In reality, a median interpretation appears possible: it is certainly true that the anamorphic technique was well known in the history of art, so much so that it appeared in the famous painting The Ambassadors (1533) by Hans Holbein the Younger, in which a skull appears at the feet of the two portrayed ambassadors which can only be seen by adopting a certain perspective, but it is equally certain that Spare's magical reflection was exactly linked to the ontological relativity of reality and to the breaking down of the conventions of space and time. Not by chance a series of these particular paintings were ascribed by Spare himself to the series 'Experiments in Relativity' [32].

There is no doubt the power exercised by the physical theory of relativity formulated by Einstein also on the fields of art and literature, and it is equally undoubted that relativity was a concept which became the prerogative of a vast series of individuals whose reflections and creations could intersect each other without apparently no other influence than that of the direct or indirect connection with Einsteinian thought. To mention the fact that in the same years, Salvador Dalì with his famous 'The persistence of memory' (1931) had reached similar anamorphic and conceptual conclusions.

The most evident aspect of this connection is not given so much by the commonality of technique used, given that as mentioned anamorphism belongs to the history of art, but by the underlying conceptual conception. Both Dalì and Spare demonstrate to some extent that they believe in asidereal truth', a concept that appears to have been borrowed from astrological semantics rather than from that typical of physics. Neither The Logomachy of Zos, Spare is very precise in outlining the foundations of this sidereal truth:

Truth is all that is past, present, and potential in conception — so truth is relative. What is true for me may not be true for you, and what is true now may not be true later, or in other times and places, so truth has a chronology in space and a "spatio-temporal" truth. There are truths that we create from our "as if" realities—environment, character, temperament, learning, etc. … Truth can be induced by obsession, faith or something committed: these are "personal truths", the "as if truths". I affirm that all lies are true when accurately reoriented to time and place, and may be called "sidereal truths."

[33]

In this perspective, the Spareian concept of 'Anon', a future-in-potential, a future created by our personal reality, makes it even more evident how much divination, Tarot and anamorphic painting are nothing more than forms of engraving of the inner will on reality, not to influence it but to create it step by step. The conventions of space and time are therefore overcome by the will, and the barriers of reality, taken as objective, demolished.

And just the very concept of overcoming the fixity of the horizon, creative, cognitive and perceptive, populated another meeting ground between Spare and the Surrealists: the more radical dynamics of geometry. As is well known, Spare was also an appreciated drawing and art teacher: during his courses he held lessons on his main influences, on the various drawing and painting techniques and above all, an authentic Spareian passion, on geometry [34].

Likewise, the non-Euclidean geometry it was an authentic exercise and battlefield for important exponents of French surrealism, starting from Man Ray [35] e Duchamp. In this sense, the deepening of the fourth dimension, located well beyond the usual coordinates, made itself something further than the mere metaphor of a hyperspace, of a parallel or inner or unexplored reality: it ended up being the eternal possibility of a replica of one's own ego, unstructured with respect to the imprisonment of normative, social, religious conventions.

Good Sorcery, Bad Sourcery: a conclusion

Despite everything, there were some Surrealists familiar with the work of AOS [36]. One of these was the British painter and occultist Ithell Colquhoun. In 1955, Colquhoun, at the express request of Antony Borrow, created for the magazine The London Broadsheet, a biographical and theoretical profile of AOS [37]. In spite of this case, and a few other blocks, however, Spare's absence since pantheon of the references of surrealism continues to be practically total.

Wishing to draw provisional conclusions, we must dwell on some factors which conspire with each other may have generated this partial oblivion. Spare's idiosyncrasy for institutional recognition and limelight, no doubt, facilitated the relative oblivion that fell like a long shadow on the physiognomy of the painter-sorcerer of Snow Hill.

The total absence of propensity to compromise, the search for a rigidly individual path, intertwined between the spiritual sphere and artistic expression, the obsessive focus on some elements deriving always and only from Spare's individuality have, united together, really constituted, wanting to paraphrase the well-known phrase, one 'medicine too strong for the average surrealist'. If only he had wanted, when very young at the Royal Academy, Spare could have enjoyed the powerful echo of the first important awards and the sounding board produced by those exploit. Yet, careless and indifferent, the painter continued on his way.

Spareian individualism constitutes one of the cornerstones of the strongest and widest divergence with respect to the structured, hierarchical, codified form of movement of surrealism: if Spare pursues, with his own methodology, a bigger design than the subsumption in the institutional devices of a structured avant-garde, the Surrealists on the contrary produce rules, norms, even processes to anyone who seems to move away from the Surrealist canon.

In this, Spare seems much more akin soul to Antonin Artaud rather than the Surrealist movement: Artaud also approached the Surrealists but withdrew from them in a very short time, so much so as to have created a friction that would later even import armed assaults by the Surrealists against cinemas 'guilty' of showing Artaud's films [38]. Artaud, so oblique, serpentine, shamanic, intoxicated with his own individuality, tended to get much closer to Spare's sensibility than any other exponent of the Surrealist movement could ever have hoped to do.

“This is how a flawed society invented psychiatry to defend itself from the investigations of certain lucid superior minds whose divinatory faculties annoyed it" [39], on closer inspection, a phrase that could be extrapolated fromAnathema of Zos, a defense of the beyond-worldly vision, of lucid madness as a method of seeing-beyond.

Without forgetting, wanting to remain in the theoretical construction that in Spare he saw the features of a proto or post-shamanic attitude, the similarity in be 'on the other side of things which will unite the English painter and the French actor-writer, especially during and after the latter's incredible experience in Mexico and which will be vividly narrated in To the Tarahumara country [40].

The Surrealists could not have appropriated Spare, to the same extent that they could not have broken Artaud: the intransigent irreducibility of both to a system other than that of one's own ego made them virtually and factually incompatible not so much with the conceptual assumptions of the surrealism as much as with the expectations and hierarchy of surrealism as an organized movement.

Some authors have also underlined how Spare's artistic misfortune would have been determined by accusations of plagiarism and artistic fraud that fell upon the young man, which would have prompted the art world to reject him [41] with increasing intensity. Although allegations and evidence give some substance to this accusation, it must be said that it is in any case chronologically placed in a period subsequent to that in which Spare could have exerted a powerful and strong influence on surrealism. Which, incidentally, does not historically appear to be a movement inclined to be frightened by something like 'copyright protection'.

There is then another aspect which, however paradoxical it may appear, overshadowed the importance of the painter Spare. And it is occultism, or rather the exposure and importance of the covert research, as it has been handed down by some of his friends, associates and biographers. It is not a question of denying Spare's mystical and esoteric philosophy but, more prosaically, of not making it prevail, as if it were a separate and parallel body, with respect to the artistic realization that of that 'system', or worse still 'cult', it was an essential and founding part.

Cult Spareian is already basically a theoretical-general gamble: there is no magical cult of Spareian Zos Kia that can ignore the individuality of Spare himself. The unfathomable and abysmal weight of his visceral urgencies, of his abysmal obsessions, has been nourished by symbols, figures, forms that can be used by others, but in modalities and dimensions that will become those who are using them at that given moment.

On the contrary, having often placed the emphasis almost exclusively on the role of sorcerer and source of inspiration for new mystical-sensorial explorations has devalued the importance of painting in Spare's general vision. Which, even in esoteric terms, is a grave perspective error given that art for Spare was an inseparable part of his magical-mysterious essence.

To a certain extent, Spare has also paid for the cumbersome proximity of some figures who have transfigured him, making him something other than his individuality. The most relevant case, in this perspective, is the one represented by Kenneth grant. Grant was a serious friend of Spare, he revived in him some precise occult interests and helped to make his name known in the ambit of the Revival esoteric, has certainly helped him in an organic and non-trivial way but at the same time has condemned him, albeit completely involuntarily, to being a Spare-character filtered through the personality of Grant himself, considerably opacifying the sources at our disposal for an academic analysis of some aspects of AOS's thought and work.

As Robert Ansell critically noted, the partnership between Spare and Grant produced, resorting to a play on words: “good sorcery, bad sorcery” [42] — good magic, bad sources. Because in fact, exactly as for Shaw's most likely apocryphal quotation, Spare's Grantian construction seems more like the desire to erect an organic system, a Spare-Master and precisely for this reason partially alien to Spare's sensibility [43]. We saw this about the 'cult of Zos Kia' [44], of the term itself 'resurgent atavism' [45], in some cases the emphasis on Grant has overwhelmed the figure of his painter friend, especially for Spare [46] he had done and represented before meeting Grant himself [47].

It should also be acknowledged that Spare's language itself was difficult to understand and in some cases an excess of theoretical-superstructural complication more than from Spare's exotic taste could have simply derived from the hermeneutical difficulty of Spare's speeches and writings, together with the notorious verbose-baroque literary taste that distinguishes Grant's prose. After years of intense work on the notes and writings of AOS, a disconsolate Grant admitted that many of those words put together, often apparently jumbled, seemed to him poorly decipherable [48].

There is one last aspect, closely connected to the difficulty of interpreting Spare's thought, which should be underlined: Spare's unclassifiability. In a world that requires labels, definitions and categories for ready consumption, unclassifiability has certainly not helped. It is undoubtedly true that from the point of view of the graphic trait and the general aesthetic Spare has more in common with the Symbolists [49] than with what years later would become surrealism.

Some paintings by Gustav Adolf Mossa, for example, appear decidedly similar to some Spareian creations. And even conceptually the symbolism betrayed a research not alien to that dear to AOS. But without any doubt and without certain similarities, the Spareian theorization in its final results completely transcended the symbolist sphere, innervating itself in devices much more akin to what would become surrealism. Which paradoxically prevented him from being considered a symbolist and a surrealist at the same time.

NOTE:

[1] V. Fincati (edited by), The Belle Epoque of esotericism – magicians, sorcerers and alchemists in fin de siècle Paris, Thesis study, Rome, 2018.

[2] A. Breton, Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), in Id., Manifestos of Surrealism, Einaudi, Turin, 1987, p. 33.

[3] K. Seligmann, The Mirror of Magic (1965), Gherardo Casini Editore, Florence, 2019.

[4] V. Jenkins, Visions of the Occult – an Untold Story of Art and Magic, Tate publishing, London, 2022.

[5] On the role of authentic logical-conceptual antecedent of Spare on Surrealism, especially on automatic writing and on the stream of consciousness, N. Choucha, Surrealism and the Occult, Mandrake, London, 1992, especially pp. 47 et seq.

[6] Which does not mean in any way wanting to forcibly force Spare into the cauldron of the surrealist movement or inferring some Spareian displeasure in not having been considered the father or inspirer of surrealism, but simply wanting to uncover salient, non-trivial, completely substantial that present in the work of Spare were then used by surrealism itself. Or, in other words, to conceive Spare as a necessary antecedent of surrealism.

[7] R. Ansell, The Bookplate Designs of Austin Osman Spare, Keriwden press, London, 1988, p. 5.

[8] R. Ansell, The Bookplate Designs of Austin Osman Spare, cit., p. 1.

[9] N. Drury, Stealing Fire from Heaven – the Rise of Modern Western Magic, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011, p. 135.

[10] K. Grant, Images and Oracles of Austin Osman Spare, Fulgur, Lopen, 2003, p. 16; the assertion has been hotly contested by Robert Ansell according to whom there is no evidence to support such a challenging and important claim.

[11] Even if, paradoxically, Spare would have become authentic proletarian painter whose livelihood was linked to performances in pubs.

[12] W. Wallace, The Early Works of Austin Osman Spare, Catalpa Press, Stroud, 1987, p. 20.

[13] F. Vasarri, Surrealism and French tradition, in Rhesis - International Journal of Linguistics, Philology and Literature, 2, 2016, p. 34.

[14] It is only necessary to recall that Spare coined the conceptualization of Atavism, but the definition of 'resurgent atavism' is by Kenneth Grant. Just as there has never existed, in Spare's lexicon, a Cult of Zos Kia, which is also quite logical considering the British painter's idiosyncrasy for organized and institutional forms of religiosity and mysticism.

[15] G. Semple, Zos Kia: an Introductory Essay on the Art and Sorcery of Austin Osman Spare, Fulgur press, Lopen, 1995, p. 26.

[16] Austin Osman Spare, The Book of Automatic Drawing, IHO books, Thame, 2005, p. 4.

[17] F. Letchford, Michelangelo in a Teacup: Austin Osman Spare, IHO books, Thame, 2005, p. 12.

[18] N. Choucha, Surrealism and the Occult, cit. p. 48-49.

[19] G. Semple, Two Tracts on Cartomancy, Fulgur press, Lopen, 1997, P. 15.

[20]"Spare had his ironic revenge: the term surrealism which Breton had appropriated, taking it from Apollinaire, was now used with studied sarcasm by Spare", G. Simple, Two Tracts on Cartomancy, cit. p. 12.

[21] G. Semple, Two Tracts on Cartomancy, cit., p. 13

[22] H. Klocker, Wiener Aktionismus; The Shattered Mirror, Ritter Verlag, Klagenfurt, 1989, p. 380.

[23]"As soon as we desire, everything is lost: we are what we desire, therefore we never realize. Desire for nothing, and there will be nothing you will not achieve', so AO Spare, The Book of Pleasure, ed. en. private curated by R. Migliussi, Livorno, 2017, p. 32.

[24] R. Svoboda, Aghora – to the left of God, Edizioni Vidyananda, Assisi (PG), 1995, pp. 133 et seq.

[25] Obeah, or Obi, is a form of witchcraft magic which has become to all intents and purposes the oldest religion of African-Creole slaves, especially practiced in Jamaica. It has rather organic assonances with Voodoo and Santeria and is based on mental and elemental associations which, using the tools of nature, lead to the occurrence of certain events.

[26] S. Chiodi, M. Duchamp, Marcel Duchamp: criticism, biography, myth, Mondadori Electa, Milan, 2009, p. 219.

[27] L. Carrington, The Tarot of Leonora Carrington, Fulgur Press, Lopen, 2021.

[28] D. Cantu, A brief evolution of “Mrs Patterson”, witch mentor to Austin Osman Spare, in Joel Biroco (ed.), Kaos 14, Kaos-Babalon Press, London, 2002, especially p. 38 for some doubts about the real existence of the woman. Doubts are also expressed by F. Letchford, From the Inferno to Zos, First Impressions, Thame, 1993, vol. 3, p. 147, who recalls that his friend Spare told him of the relationship with the woman in very vague and generic terms, without ever going into biographical details of the hypothetical witch. The figure of Paterson has always represented one of the most debated points of fall for the exegetes of Spareian thought and life. One wonders if she really existed, and if so what real influence she exercised on the young Spare, or if on the contrary it was not the vivification of a mental projection of the artist.

[29] J. Allen, Lost Envoy – The Tarot Deck of Austin Osman Spare, Strange Attractor press, London, 2017. The book, which has long been out of print, will be reprinted in 2023 following the success of a crowdfunding project. Spare created his 79 cards in 1906, when he was very young, constituting an innovative model of self-learning through the cards themselves. On the one hand, he hybridized the classic figures of the Tarot with the suits of the card game and on the other, as already noted in the body of the text, he reformulated the imaginary of the Tarot using his own figures and creations.

[30] MM Jungkurth, “Tree of Knowledge – Good and Evil” in G. Beskin, J. Bonner (eds.), Austin Osman Spare: Artist Occultist Sensualist, Beskin press, London, 1999, p. 51.

[31] F. Letchford, Michelangelo in a Teacup: Austin Osman Spare, Mandrake press, Thame, 2005, p.215.

[32] S. Pochin (edited by), Austin Osman Spare, Fallen Visionary: Refractions, Jerusalem press, London, 2012, pp. 70-71.

[33] K. & S. Grant, Zos Speaks – Encounters with Austin Osman Spare, Fulgur, Lopen, 1998, p. 178.

[34] On the passion and competence for geometry applied to artistic creation, widely, AA.VV. 'The Static Aligments: Austin Osman Spare's School of Draughtmanship', Jerusalem press, London, 2021.

[35] L. Dalrymple Henderson, The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art: Conclusion, in Leonardo, 3, 1984, pp. 205 et seq.

[36] Incidentally, it can be noted as the introduction to the second volume of the monumental work From Hell to Zos, was drafted by Professor Roger Cardinal, a distinguished scholar of the history of surrealism as well as a passionate scholar of art brut and outsider art (a term coined by Cardinal himself).

[37] A. Hale, Ithell Colquhoun – Genius of the Fern Loved Gully, Strange Attractor Press, London, 2020, pp. 205 et seq.

[38] On these aspects, as well as on the rigidly orthodox and hierarchical climate within the Surrealist Movement, populated even by processes to decree removals, punishments and expulsions, L. Bunuel, Dei mia sospiri extremi, SE, Milan, 2009.

[39] A. Artaud, Van Gogh - The suicide of society, Adelphi, Milan, 2000, p. 14.

[40] There is a moment in Artaud's journal of shamanic exploration that seems to echo the Spareian distinction between symbolization and sealing, and it is when Artaud is confronted with trees intentionally burned to symbolize crosses and others'perfectly conscious, intelligent and concerted signs', A. Artaud, In the country of Tarahumara, Adelphi, Milan, 2009, p. 73. At the same instant, Artaud experiences a psycho-historical epiphany which makes him intensely experience the sense of an occult permanence and of a significant irradiation which brings together the mystery of the Rosicrucians, the archaic and ancestral wisdom of Mexican shamans, the mystique of the Grail, in a whirlwind of counter-realities determined by the power of the signs and by the perception of Artaud himself.

[41] ARNaylor, Stealing the Fire from Heaven: Austin Osman Spare, IHO books, Thame, 2002, especially pp. 9-22.

[42] S. Magus, The Fin-de-Siècle Magical Aesthetic of Austin Osman Spare – Siderealism, Atavism, Automatism, Occultism, in Academia.edu, p. 3.

[43] M. Lee, “Memories of a sorcerer': notes on Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, Austin Osman Spare and anomalous sorceries, in Journal for the Academic Study of Magic, 1, 2003, especially p. 124.

[44] Grant argued that the cult of Zos Kia would have been institutionalized by the synergy between himself and Spare according to a methodology that Spare would have shown and taught him in 1948, thus K. Grant, Outside the Circles of Time, Muller, London 1980 , p. 140, note 10. The problem is that, as Grant admits in another book, the meeting with Spare took place only in 1949, thanks to the intercession of his wife Steffi who had met Spare during the same 1949… Thus, K. & S. Grant , Zos Speaks!, cit., p. 29. In 1948 it would seem that the first merely fact-finding correspondence had only begun to grant the benefit of the date by probing other letters. Not satisfied with these contradictions, and perhaps trying to remedy the one contained in the first edition of Outside the Circles of Time, in the new edition of the volume Grant made the date 1952 the most suitable (about, grants Grant), see in this regard the Italian edition edited and translated by Roberto Migliussi, K. Grant, Oltre i Cerchi del Tempo, Psiche2, Turin, 2018, p. 168, no. 10, but also in this case the contradictions did not cease; in fact, in another letter, used by Fulgur for example to draw up the biography of Grant that stands out on their website, the date was transformed into 1954. It should only be noted, in this last case, that Spare spent the last years of the his life in a great state of breathlessness and physical prostration, undermined as he was by a series of non-trivial ailments that would have led him to the grave in 1956 and to imagine that in those conditions he could codify, even if only theoretically, a magical cult is an exercise of pure style.

[45] However, while 'resurgent atavism' is a synthetically effective definition that does not overwhelm Spare's theorization but rather strengthens it, the 'cult of Zos Kia' ends up determining a functional institutionalization of Spare's thought in an occult key. Naturally we do not want to deny that Spare could also be interested in transmitting his own occult knowledge, to the same extent that he exercised the function of art and drawing teacher, which however is something very different from theorizing a 'cult' or a ' I believe', however much the term may aspire to synthesize and systematize a thought which, however, in the case of Spare, anarchist, individualist, focused on his own projections and on his own indecipherable terminology, could in no way be systematized.

[46] In this sense, for example, Jan Fries, Visual Magick, Mandrake, Oxford, 1992, p 42.

[47] Apparently in some cases it was indigestible for Spare himself who addressed a good-natured one reprimand to Grant calling his written language excessively verbose, K. & S. Grant, Zos Speaks!, cit., p. 68. The same Aleister Crowley, criticizing the excessive Byzantinism of the language, both written and spoken, Grantian, addressing the disciple to whom he had asked a question, hearing a torrential and convoluted answer replied 'I asked you to give me an answer, not give me a sermon', K. Grant, Remembering Aleister Crowley, Skoob books, London, 1991, p. 58.

[48] K. & S. Grant, Zos Speaks!, cit., p. 128.

[49] P. Baker believes that a more proper conceptual association is that between Spare and symbolism, P. Baker, Austin Osman Spare, in C. Patridge (ed.), The Occult World, Routledge, Abington, 2015, p . 306.