Baudelaire's correspondence theory, in its formulation, owes much more to Maistre than to Swedenborg. When Baudelaire sees the world as "a forest of symbols", he introduces us to the Maistrian method of relating the visible to the invisible.

Article originally published in French on MauvaiseNouvelle.fr

Translation by Marco Maculotti.

Modern exegetes and biographers indulge excessively in suspicion, devaluation and even acrimony towards the works with which they are concerned, making it their forte and the outlet of their resentment at being confined to a secondary role. While the traditional commentary is based on a principle of reverence and fidelity that pushes him, through his interpretation of him, to continue on the path opened by the work that distinguishes and to which he is dedicated, the modern commentator generally finds it more "rewarding" to suspect the author and find the speck in the eye of the work unaware of being contemplated by it as much as he examines it. More often than not, the suspicious exegete paints his own portrait, with his own beam.

When Sartre suggests that Baudelaire's reading of Maistre is summary, that he obeys subordinate and superficial reasons, he speaks to us of his own reading of Joseph de Maistre, and at the same time gives us his self-portrait: «an austere and bad faith thinker». Joseph de Maistre can be criticized for everything, except of course for being an "austere" thinker. If there is a work that has resisted Puritanism in all its forms, it is that of Joseph de Maistre: the distrust that moderns feel towards him cannot be explained otherwise. Strict followers of virtue and terror, of a morality devoid of any metaphysical or supernatural perspective, adversaries of aesthetes and dandies (the ultimate guardians of the concordance between the True and the Beautiful), the moderns have made austerity and bad faith the their theoretical and practical weapons to exterminate all theological vestiges, wherever they were.

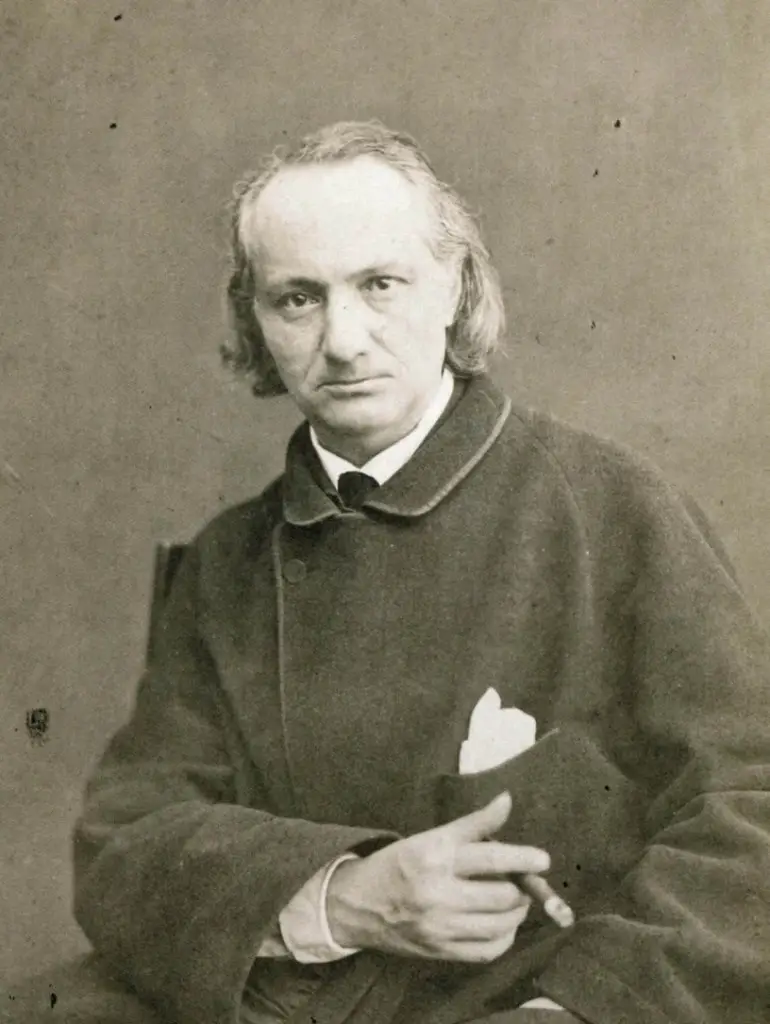

Joseph de Maistre's influence on Baudelaire is one of the most profound a thinker has ever exerted on a poet, although we must not forget that Maistre, in Les Soirées de Saint-Pétersbourg (“The evenings of St. Petersburg” or “Conversations on the temporal government of Providence”), is a poet on an ongoing basis, as well as Baudelaire, in his poetic and critical works, in his aphorisms and in the notes of Mon cœur mis à nu (“My Heart Laid Bare”) never stopped being an astute metaphysician. Baudelaire recognizes himself in Maistre as he owes him the main aesthetic and philosophical principles of his method. Baudelaire would undoubtedly have been a Maistrian without even having to read Joseph de Maistre, so much did his taste and his mysterious and providential affinities match Joseph de Maistre's preferences. But, in the sense in which Valéry speaks of Leonardo da Vinci's method, there is a Baudelairian method, and he owes everything to Joseph de Maistre.

Baudelaire's correspondence theory, in its formulation, owes much more to Maistre than to Swedenborg. When Baudelaire sees the world as «a forest of symbols», he introduces us to the Maistrian method of relating the visible to the invisible:

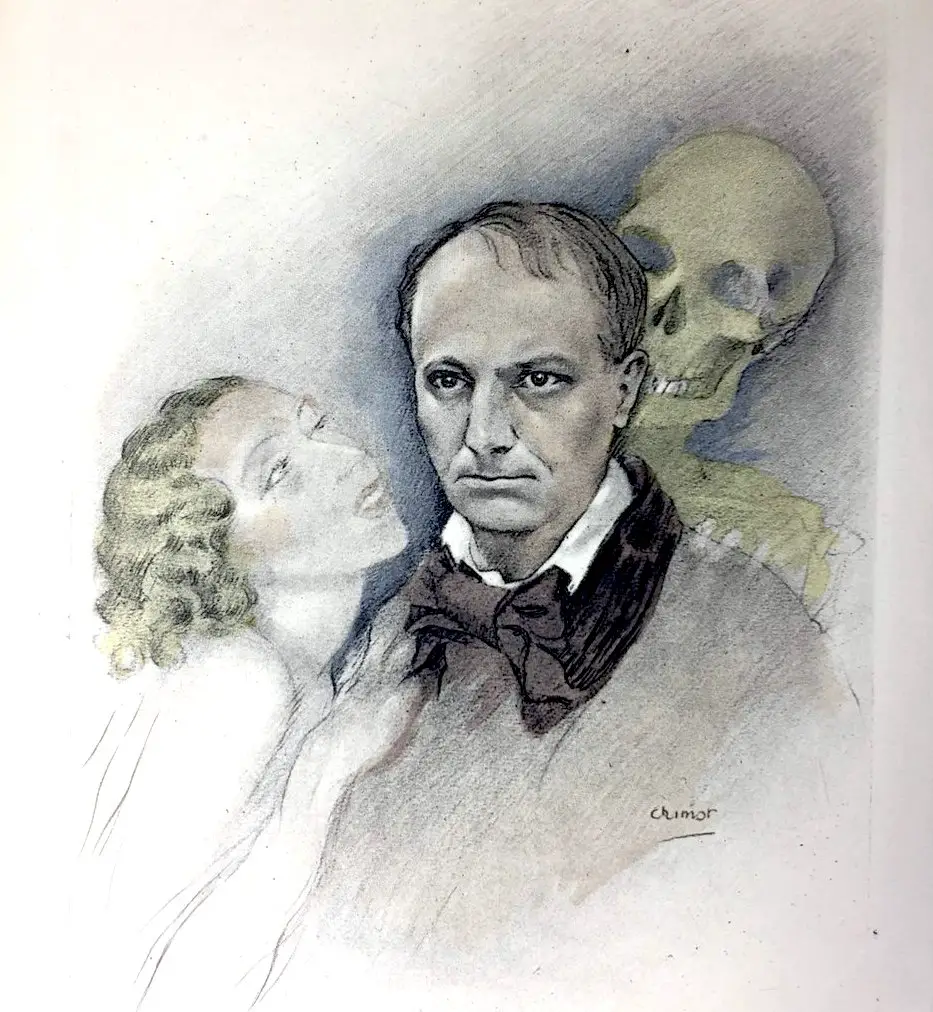

No one can deny the mutual relations of the visible and invisible worlds.

We remember once again that the word Devil comes from diaballein, which means to disunite, while the word Symbol, from the same root, derives from the verb sumballein, meaning to unite or bring together. There is no sentence in all of Baudelaire's work that does not respond to Maistrian's meditation on Evil and the works of Divine Providence. The essential paradox of Baudelaire's work and of human response to it comes from a constant meditation on Saint-Pétersbourg soirées. Evil exists, but it is only the disunity of Good; the Devil is the prince of this world, but he is only a part of the Symbol that unites and saves. The Flowers of Evil are not some cheap, Halloween-style Satanism (Evil really is in the mockery of the cheap), but a retroactive proof of the sumballein. Good does not oppose Evil; it is Evil which, when Good triumphs, returns within Good, to disappear. Raymond Abellio writes:

The abyss of day contains the abyss of night, but the abyss of night does not contain the abyss of day. The fact remains that two forces coexist in us, or more precisely two postulations: «There are in every man, at every hour, two postulations, one towards God, the other towards Satan». No less Maistrian is this corollary consideration: «We observe that those who abolish the death penalty must be more or less interested in abolishing it. They often are guillotiners. It can be summed up like this: I want to be able to cut off your head; but you won't touch mine. Those who abolish the soul (materialists) are necessarily those who abolish hell; they are certainly interested in it; at the very least, they are people who are afraid to live again — lazy people.

Sartre ignores Maistre's influence on Baudelaire as much out of ignorance of Maistre's work as out of misunderstanding of Baudelaire's work. We therefore allow ourselves the freedom to judge Maistre's work in bad faith and to consider Baudelaire's work with that puritanical austerity which is the characteristic of intellectuals by antiphrases, that is, of "intellectuals" whose only raison d'etre is to fight the Intellect as a theological and metaphysical perspective. Baudelaire refers to Maistre as the author who exercised the decisive influence on him, in terms of thought and style: this is enough for Sartre's bitterness to judge Baudelaire a liar. It is true that the poet has the inalienable right to move away from the relative truths of "realism" and to go in search of a deeper, more essential truth, which will appear first, in its emanation, under the guise of clouds and mysteries, but as soon as we consider Baudelaire's poetic and critical work as a thought, that is, as a "correct weighing", an analogical art in which prosody and metaphysics are ordered to a theory and a method of ratios and proportions, the name of Maistre and the reference to Saint-Pétersbourg soirées they appear as a key.

Baudelaire believed so strongly and so rightly in the relevance and truth of his thought that, far from trying to appear original by hiding his influences and encounters, he never stopped trying to support his work with other older or more contemporary works. What is said seems to this dandy more important than who says it — which throws some light on theactive impersonality of Baudelairean dandyism, which is very different from the modern "cult of the ego" — and in this sense he is even more different from Sartre than, under the title of Being and Nothingness ("Being and Nothing"), indulges in more or less persuasive, if not convincing, variations, largely without referring to the author of Time and time.

Baudelaire inserts Maistre in his work as a point of reference, to which the reader is called to refer in order to understand what he is about to read, just as Schopenhauer opens The world as will and representation with a reference to Kant. Human timescales are short; when certain principles have been perfectly stated, when a method stands and proves its effectiveness, it is advisable to cut it short and face it immediately. The distinction between the modern exegete and the traditional exegete that we outlined above is accompanied by the distinction between two types of authors. The former never cease to regret the fact that others have already gone their way before them, while the latter rejoice: they are among those who will go further. The former are jealous and would be ready to reformulate everything in their own way; the latter, who generally cultivate the ancient and aristocratic taste ofotium, they would like to find the work they are thinking about already written by someone else. The others think, as the Hindus say, like the kshatrya: they are honored to to serve an impersonal True, Good and Beautiful. Joseph de Maistre wrote:

Every belief which is consistently universal is true, and whenever, by separating from a belief some articles peculiar to different nations, something common remains, what remains is a truth.

La Sophia perennis or, more precisely, what René Guénon would call the primordial Tradition, is the keystone that unites the work of Baudelaire to that of Maistre. Metaphysical or supernatural truth is universal by definition. This is why for Maistre, as for Baudelaire, the differences between peoples are less important than the differences of caste, which are of an entirely different nature from the differences of class. Baudelaire wrote:

There are only three respectable beings: the priest, the warrior and the poet. Know, kill and create. The other men are tailorable and portable, made for the stable, that is, to exercise what we call professions.

In this way, Baudelaire prolongs Maistre and replies in advance to Sartre, who dares to write: «And just to the extent that Baudelaire wants to be something in the middle of Maistre's world, he dreams of existing in the moral hierarchy with a function and a value, just as the luxury suitcase or the domesticated water in jugs exist in the hierarchy of utensils». Hence Baudelaire's prophetic need to specify:

Being a useful man has always seemed to me to be quite obnoxious.

It should be noted in passing that Sartre, while attaching a completely different meaning to the metaphor, involuntarily recalls the distinction between esotericism and exotericism, «the water and the amphora» of which the Sufi poets speak. If Baudelaire wants to be the water, no doubt Sartre would prefer to be the carafe! Baudelaire is Maistrian precisely because he heroically chooses to escape any exploitation, any utility, any function that predisposes him to recognize, beyond any decantation, the supreme transparency of metaphysical truth:

The only interesting things on earth are religions. […] There is a universal religion, made for alchemists of thought, a religion that emerges from man considered as a divine memory.

Sartre is completely wrong when he writes, not without a touch of meanness, that «Maistre's influence on Baudelaire is mainly superficial; our author found it 'distinguished' to claim it as his own», but this error, like all errors, is not meaningless: it proves that for Sartre it is the carafe that gives meaning to the water, not the water that gives meaning to the carafe. All of Sartre's subversion, and modern subversion, can be reduced to this inversion, which is also the hallmark of all fundamentalisms, which have the wrong name because they exalt the accessory, the utensil, to the detriment of meaning and its metaphysical universality. Utilitarianism demeans man, hence the need for Baudelaire to formulate a theory of the superior man. In religion, as in politics, utilitarianism reduces everything to bargaining, to the commerce that divides being and appearing. Baudelaire wrote:

Commerce is satanic in its essence. Commerce is the loan repaid, it is the loan with the implication: give me back more than I give you.

Plunged into the quagmire of bourgeois France, Baudelaire must have found in the conversations of the Senator, the Count and the Chevalier a happy refuge and a sort of testimony of that musical intellectuality of which he sought, through his fidelity to Racine, to interpret the discrepancies and the nostalgia in the soul abandoned in the squalid atrocities of the middle classes. Baudelaire had foreseen what Hannah Arendt would call the banality of evil. At the height of his Maistrian demands he wanted to hurl literary modernity against the modern world, just as he ironically implored Satan to have mercy on his long misery. When Maistre, in Les Soirées de Saint-Pétersbourg, makes the Count say «Original sin, which explains everything and without which nothing can be explained, unfortunately repeats itself at all times, albeit in a secondary way», Baudelaire intervenes clarifying his theory of true civilization: «It's not in the gas, nor in the steam, nor in the record players, it's in the diminishing of the traces of original sin».

From the point of view of history, Baudelaire is the point where the discourses have set. The time is ripe for progressivism, the «doctrine of the lazy», which means, for Baudelaire, that the time has come to break with all forms of collectivism and gregariousness. The paradox is only apparent. Indeed, there is a world beyond and above the individual, and the world to which the «doctrine of idleness» is a world which destroys at its very core any transcendence of the individual. The least we can do is have been what we are meant to be. Baudelaire, in whom we tend to see the model of the asocial, remains faithful to the Maistrian idea of society as a civilization, «faithful and perpetual custodian of the sacred deposit of the fundamental truths of the social order, society, considered in general, communicates them to all its children when they enter the large family, reveals to them the secret through the language it teaches them».

Noting the disappearance of the sacred deposit and of the despised, shredded and plundered language, Baudelaire does not give in to the illusion of empty form: the empty carafe does not quench his thirst, the parody of the order that the bourgeoisie imposes with extreme rigor does not seem at all amiable to him, in a word, determined to «dive into the unknown to find something new». Far from the facade of the Maistrian bourgeois reactionaries, Baudelaire invents the praxis of the theory which Maistre formulates as follows: «the re-establishment of the monarchy, which we call a counter-revolution, will not be a contrary revolution but the opposite of a revolution».

Where the revolution mobilizes, plans and exploits, Baudelaire takes charge of demobilizing, of increasing the sense of singularity and of celebrating the useless. A rigorous application of the method he had found in Maistre, his dandyism, so misunderstood, truncates any desire for collective action, appeals to the people, mobilization of troops, referendums or elections:

What do I think about voting and the right to be elected? Of human rights? What's ignoble about a charge? A Dandy does nothing. Can you imagine a Dandy speaking to the people, except to despise them?

Baudelaire's dandyism, his unknown and innovative character, consists in staying where we are, stubbornly. This isn't a bad strategy, by the way; it spares us battles in which we would have inevitably been defeated. For Baudelaire, the dandy is not the effeminate egoist, but the custodian of the sacred deposit, the witness of the Idea:

To be a great man and a saint to yourself. This is the only important thing.

The dandy is his own witness, which suffices to say that for Baudelaire it is not only an ego imprisoned in immanence, but the subtle diplomat of the Idea:

Every idea is, in itself, endowed with an immortal life, like a person. Every form created, even by man, is immortal. Because form is independent of matter.

While the Revolution and the Counterrevolution precipitate the "doing" and the "undoing" into the inane and the vulgar, the «opposed to a revolution» maintains being, during the interregnum, in the fullness of its possibilities. Baudelaire, thinker of the extreme, carries the Maistrian premise to its logical conclusion, rigorously applying it, persisting in a way of being that is also a way of speaking. Baudelaire's lucidity frees his pessimism from the temptation to sin against hope. The Maistrian lesson keeps Baudelaire on guard: «We challenge the people, common sense, heart, inspiration and the obvious».

All revolutionary and counter-revolutionary romanticism, so cumbersome and cacophonous, is thus thwarted in a single sentence. The important thing is to safeguard the music and the space. As Baudelaire writes: «The music gives the idea of space. All the arts, more or less; since I am number and number is a translation of space». The poem reiterates it: «Music digs the sky».

The poet's immobility preserves spaciousness and unity.