From the analysis of the two mythological figures of Puer Aeternus and Kore in the demetric mysteries of Eleusis, in the studies of the Hungarian historian of religions Károly Kerényi and in the comments on these by Carl Gustav Jung, the importance of the "original" and "founding" character emerges "Of the Greek myth, the enigmatic link between being and non-being, the one between life, love and death that allow us to express through symbolic relationships a cosmic process in which man's existence is close to reality.

di David Simonato

taken from the thesis "The image of man in the works of Walter F. Otto, Károly Kerényi and Mircea Eliade", 2014-15

cover: Frederick Leighton, "The Return of Persephone"

The problem of non-being according to the religious vision of the Greeks was the theme of the essay placed as an epilogue to Ancient Religion, in which Karoly Kerenyi he pushed himself to confront some of the most interesting positions of contemporary philosophy. The nihilistic idea of death understood as a null void was contrasted with that of antiquity, according to which it was instead included within the vital horizon, as limit that in the darkness guards the principle of life [1].

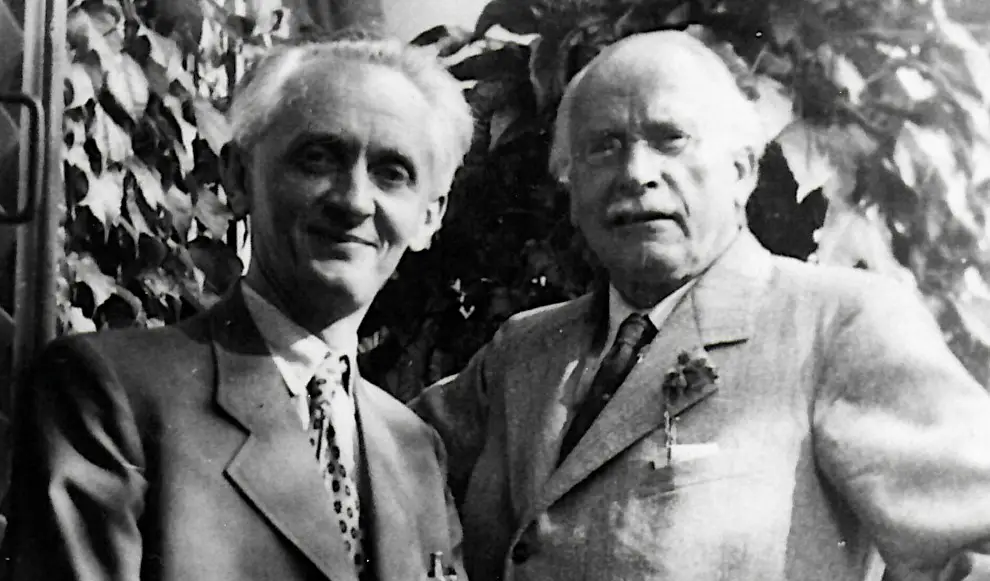

It is difficult then not to read Kerényi's subsequent two essays as the logical continuation of a discourse which, after that symbolic conclusion, did not seem destined to continue. Focused on the mythological figure respectively of the divine child and divine maiden, these writings will become famous thanks to their subsequent volume collection, which includes two extensive commentaries by Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) [2] on the corresponding psychological archetypes. At the heart of the studies contained in the book, which do not in any way accord with the high-sounding title, Prolegomena to the scientific study of mythology [3], there is the figure ofUrkind, the original child, analyzed both in its masculine and in the feminine aspect, but above all, as Kerényi states at the end of the first contribution, which "Eternal Indeterminate" [4].

Indeed, the child already born yet still poised between the differentiated and terrestrial form and the eternally indeterminate figure, swaying on the water, is the emblem of the state of transition between being and non-being. Located between the two kingdoms, even closer to the Hereafter than to the Hereafter, it participates in those "models" in which it is not difficult to recognize the primordial symbols, the archetypes [5]. The archetype for Kerényi has the function of integrating the term "human" when the traditional use has made it too vague and generic an expression. The reappears in another form need to recover the vital flow of lived experience and concrete human values, the models of eternal conditions of existence [6].

La aquatic symbology, a peculiar characteristic of the mythologem of the child, also constantly returns in the pages ofIntroduction by Kerényi, entitled Origin and foundation of mythology, an important moment of theoretical reflection. It should be taken and drink pure spring water so that this penetrates us and strengthens our latent mythological ambitions.

Yet, here too there is still much that separates the mouth from the rim of the chalice. [...] We have lost immediate access to the realities of the spiritual world - and to this belongs all that is authentically mythological - also because of our scientific spirit which is too ready to help us and too rich in subsidiary means. It had explained the drink in the chalice to us, so that we, better than good old drinkers, knew in advance what was inside. [...] We must ask ourselves whether the immediacy of experience and pleasure in the face of mythology is still possible in general [7].

As he wrote, quoting a verse from The sonnets to Orpheus by Rilke, "He who spreads like a spring is known by knowledge " [8]. Although the declared purpose is precisely that of finding access to the realities of mythology, where is this source located? The Rilkian passage quoted continued as follows: "e entranced him to the serene work / where the beginning is often an end, and the end is the beginning " [9]. Kerényi it shows itself confident of possibility of grasping the meanings of the work, in this case mythological, thanks to the interpenetration between the knowing subject and the object:'the only way seems to be to let the mythologems speak - not being able to live them anymore - and simply listen to them. Indeed "Mythology, like Orpheus' severed head, continues to sing even after his death, even long after the time of his death" [10]. Just as the life of ancient man rediscovered its own expression and meaning by immersing itself in the models of the past,

Mythology clarifies itself and everything in the world not because it was invented to explain, but because it has the power to clarify [11].

Myths would explain nothing, in any sense, and never: they set a precedent that is ideal and a guarantee of continuation [12].

The purpose of the mythologems would be precisely to justify the world by bringing it back to its foundation, to ἀρχαί, the primordial, vital and inexhaustible elements. Mythology always tells about the origins and what is original: for the narrator of myths this was equivalent to the truth. In what foundation does man find himself, his mythical identity par excellence, the point of unity around which and from which he builds his own future?

The two mythologems [...] they serve to show us through the images of human and vegetal becoming the road on which the "foundation" takes place as a path to ἀρχαί to then redo with us the path of its unfolding in those images. Figuratively we can speak of an immersion in ourselves, which leads to the living germ of our totality. [...]

The mythological "founding" [...] has this paradoxical: whoever withdraws into himself in this way opens up. Or vice versa: being open to the world, characteristic of ancient man, places this on its own foundation and makes it recognized in its own origin. [...] the origin par excellence. In the image of a divine child, of the firstborn of the origins in which an "origin" occurred for the first time, the mythologies do not speak of the production of a human being, but of that of the divine universe or of a god universal. [...] It is the world that speaks of the origin in the images that arise. He who in that submersion has reached his own foundation, "founds" his world [13].

In fact, an act of equally religious and spiritual value corresponds to the myth of the origins: the foundation. Living the myth is like going back to one's “origins”, to one's constituent elements and always reorganizing them anew. As Jung wrote about the mandala, in a passage reported by Kerényi at the end of a brief examination of the foundation myths,

"Things of this kind are not invented: they must always resurface from the depths of oblivion to express the extreme glimpses of consciousness and the highest intuitions of the spirit, and in this way to merge the uniqueness of the consciousness of the present with the primordial past of life» [14].

The search for the origin can only be resolved in recounting the ways of appearance of the same mythological idea. Through a review of the many myths concerning the great figures of the divine child of various mythologies - Apollo, Hermes, Dionysus, Jupiter, the god of the Voguli, the Kullervo of the Kalevala - with a vast knowledge of analogies and parallels in the ethnological field, the first essay [15] aims to show how these present traits so profoundly common as to result as variations of a single motif: the infantile and timeless form of the young as fullness of life and meaning [16].

Kerényi's writing, highlighting the typical nature of mythologeme, gave Jung the opportunity to confirm its "archetypal" nature, reproduced in its essential structure in such different historical-geographical situations. Jung had indeed named "Archetypes" (Archetypes) the contents of the collective unconscious, the images belonging to the whole of humanity, and the investigation presented by the Hungarian scholar could easily be compared to his conclusions concerning the existence of mythopoetic structural elements [17]. Jung's investigation, enriching itself with suggestions that point decidedly in other directions, nevertheless pursues very different purposes from that of confirming Kerényi's results. [18].

The complementary study dedicated to Kore investigates the feminine aspect of the mythology [19]: the divine maiden of the beginnings contains within herself, in an involuted form, the figures that later will take on the names and forms of Persephone, Hekate and Demeter. This divinity that is birth, birth and death at the same time, lasting and indestructible existence, expresses in his figure both openness to the world and enclosing oneself. In Eleusis, therefore, we return to the allegorical theme of the dividing line that separates being and non-being. Kore and Persephone express the two forms of female existence at their extreme:

in a balance in which one of these forms of existence (the girl with the mother) appears as life, the other (the girl with the man) as death. Here mother and daughter form a unity of life in a borderline situation: a unity of nature that carries within itself, equally by nature, the possibility of breaking apart. [20].

The Kore therefore alternates, considered only under its aspect more human, that is, a being who at the height of inviolate life falls victim to destiny, to Persephone, whom he represents a destiny that in fulfillment means death and royalty in death [21]. After the girl and the bride, the mourning mother Demeter completes the triad of female figures, introducing the key idea of the whole mythologem of the girl: the rebirth.

Entering the figure of Demeter, that is to say being persecuted, robbed, even stolen, not understanding but getting angry and saddened, but then getting back and being reborn: what else does this mean if not to implement the broader idea of being alive, of the fate of mortals? What remains here for the figure of Persephone? Undoubtedly what, in addition to the endless drama of being born and dying, is inherent in the structure of living beings: precisely theuniqueness (uniqueness) of the single being, and its belonging to the non-existence. Uniqueness and non-existence - not philosophically conceived, but seen in figures or, to be more exact, the last seen in the amorphous, in the realm of Hades. That's where he reigns Persephone - the eternal-only fall into non-existence [22].

Once again the extreme topicality of the mythological figures finds its justification in the ability to express through symbolic relations a cosmic process in which man's existence is close to reality. Indeed, the experience of worship is both universal and singular at the same time: the lived event bears the sign of the divine and as such is represented, however much it expresses the enigmatic link between life, love and death. The initiate was not afraid of experiencing this paradox. The relationship is known that i Eleusinian mysteries they entertained with agrarian cults and more generally with the cycle of organic life, and the conclusion of the essay strongly reaffirms this union between individual destiny and the world.

The Greek was aware not so much of the "abyss" - the "abyss of the seed" - which opened up to him, as of the existence into which that abyss flowed. The "infinite series" here meant precisely infinite existence: "existence" simply. This existence was lived almost as a seed of the seed, as one's own experience. The knowledge about this did not become discursive thought or word. [...] Contemplation and contemplated, knowing and being, here as well as elsewhere in the way of thinking and existing of the Greeks, come together in unity [23].

Knowledge without words would most eloquently express awareness of one's destiny, precisely because the aim pursued is not to form an opinion about an object, but to arrive at its own level. To rise to the level of phenomena by accepting to question the established principles is the compromise to know the possibilities of human existence explained in the mythological figures.

Note:

[1] Karl Kerenyi, Ancient Religion, cit., The religious idea of non-being [and. or. Die religiöse Idee des Nichtseins, 1940], pp. 171-191. The latest edition, from which we quote, instead places the essay at the center of the book.

[2] On the relationship with Jung and psychology see Aldo Magris, on. cit., pp. 87 ff. Regarding the story of this joint publication, it is important to point out here how Kerényi's works precede his contacts with Jung. It is also questionable whether the proximity to Jung somehow follows the same necessity as Mann in his confrontation with Freud.

[3] Carl G. Jung - Károly Kerényi, Prolegomena to the scientific study of mythology, Turin, Bollati Boringhieri, 1972 [ed. or. Einführung in das Wesen der Mythologie, 1941]. The Italian title also clashes with what he writes Kerényi in the first lines ofIntroduction (see infra): a more correct translation would be Introduction to the essence of mythology.

[4] See. Ivi, P. 106.

[5] See. Furio Jesi, Literature and myth, Turin, Einaudi, 1981, P. 149.

[6] See Aldo Magris, op. cit, pp. 112-113.

[7] Carl G Jung - Karoly Kerényi, op. cit., Introduction, pp. 13-14. The writing extends to pp. 11-43.

[8] See. Ivi, p. 17. "Wer sich alsQuelle ergießt, den erkennt die Erkennung. "

[9] "Und sie fuhrt ihn entzückt durch das heiter Geschaffne, / das mit Anfang oft schließt und mit Ende beginnt. "Die Sonette an Orpheus, Zweiter Teil, XII, in Rainer Maria Rilke, Poems (1907-1926), edited by Andreina Lavagetto, Turin, Einaudi, 2000, pp. 376-379.

[10] Carl G. Jung - Károly Kerényi, op. cit., P. 17.

[11] Ivi, P. 18.

[12] Ivi, P. 20

[13] Ivi, pp. 23-24.

[14] Ivi, p. 30. His italics.

[15] Ivi, The divine child, pp. 45-106 [ed. or. Zum Urkind-Mythologem, 1938].

[16] See also Angelo Brelich, Review a CG Jung - K. Kerényi, Einfürung in das Wesen der Mythologie, «Studies and Materials of the History of Religions, XVIII, 1942, pp. 115-116.

[17] I clarify the concept of here with a note archetype according to Jung's conception. Starting from the analysis of the dreams and psychoses of his patients, Jung found that certain images, concepts and situations presented innumerable connections, which could not be compared except in the associations of mythological ideas. Excluding the hypothesis that these were forgotten cognitions, Jung came to the supposition that these were indigenous revivals independent of tradition. Unlike Freud, who considered the unconscious to be an empty container at birth, gradually filled with psychic material unacceptable to consciousness, for Jung the personal unconscious already contains "a priori forms", which are part of the so-called "collective unconscious" , and which allow us to transcend ourselves, through the symbolic function. Some symbols have a universal recurrence, which refers to the existence of those that Jung calls archetypes, that is, literally models (as Jung himself underlines the expression archetype is the explanatory paraphrase ofeidos Platonic and is already found in Philo of Alexandria with reference to the image of God in man). The archetypes they are not ideas, but possibilities of representations, that is dispositions to reproduce virtual forms and images, typical of the world and of life, which correspond to the experiences made by humanity in the development of consciousness. They are inherited and represent a sort of memory of humanity, sedimented in the collective unconscious, and therefore present in all peoples, without any distinction of time and place. The archetypes they leave their traces in myths, fables and dreams, which contrary to what Freud thought, are not the fulfillment of purely individual desires linked to infantile sexuality, but expressions of the collective unconscious. The archetypes they never present themselves to analysis in a pure state, but through their manifestations in symbols: each individual perceives them as needs and can express them in a historically variable way, according to different ethnic, national or family situations. In this way, the collective unconscious, through the archetypes, it can condition and direct the conduct of the individual in his relations with the world, inducing him to repeat collective experiences.

See the studies contained in Carl Gustav Jung, Works, 9. i. Archetypes and the collective unconscious, Turin, Boringhieri, 1980.

[18] Jung interprets the child as a symbol of the infantile and embryonic stage of the development of the collective psyche. In the Kore he instead he will read the figure of the "Self" and the "soul", the female element present also in the male personality.

[19] Carl G. Jung - Károly Kerényi, op. cit., Kore, pp. 149-220 [ed. or. Core. Vom Mythologem des göttlichen Mädchens, 1939].

[20] Ivi, P. 160.

[21] See. Ivi, P. 162.

[22] Ivi, pp. 180-181.

[23] Ivi, pp. 218-219.

.

5 comments on “The Puer and the Kore for Károly Kerényi: uncertainty, origin and foundation"