A paradigmatic case of pre-modern "micro-history": that of Pellegrina Vitello, the witch who escaped the stake of the Inquisition in Messina in the sixteenth century.

di Nicholas May

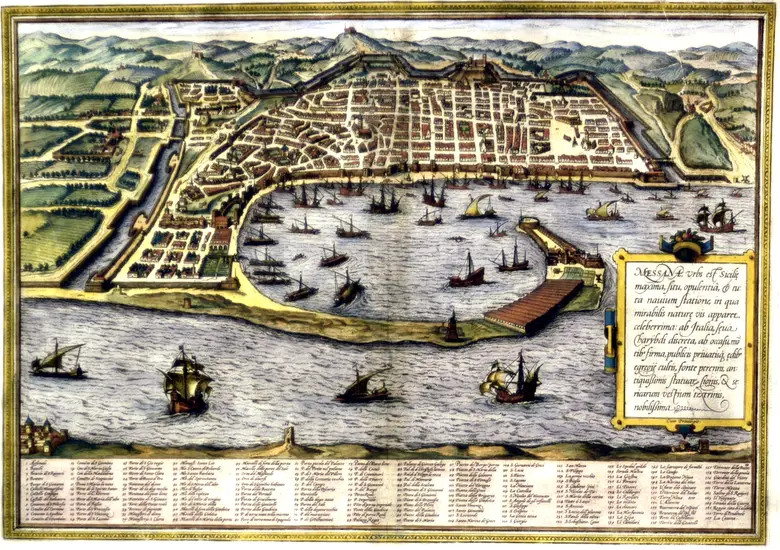

The story of Pellegrina Calf, a woman of Neapolitan origins accused of "maybe"(Or witchcraft) and tried in Messina in May 1555 by the Court of the Inquisition, which fortunately escaped the stake, is the mirror of a singular event and, at the same time, of the ways in which the Sicilian Inquisition, especially in the western area of the island, operated and acted in the sixteenth century with regard to cases of witchcraft, heresy or behaviors considered desecrating and immoral, such as blasphemies, practices of bigamy, incitements to revolt or acts considered destabilizing for Catholic orthodoxy. But it is also evidence of a Messina society in economic and commercial turmoil, gravitating around the thriving free port of the city, in which there are, however, cases of customs, practices, rituals connected to popular traditions, beliefs and superstitions.

The historical fact

Pilgrim arrives in Messina from Naples in the first half of the XNUMXth century, together with her husband Nardo Vitello, a silk worker in search of fortune and better job prospects, who soon abandoned his wife for another woman. Left alone and in financial straits, she Pellegrina tries to make ends meet by organizing, together with some accomplices, some small scam with a magical-esoteric background, boasting divinatory powers, using amulets and peculiar objects commonly considered a vehicle of Magic powers.

In March 1555 the thirty-year-old Pellegrina comes accused by five elderly Messina women, which sources indicate as "pious and Catholic", of maybe, or witchcraft (a term still in use today in the Sicilian / Messina dialect, next to mavaria, to indicate the act of witchcraft or of cursing an object or person, while with mavara the subject carrying out the action is indicated). Presenting himself before the judges of the Saint Tribunal of the Inquisition, the five women accuse Pellegrina of having performed spells of various kinds, jinxes, prepared hexes, invoked demons, as well as to have visions in trance while observing a jug of water in which strange black bodies with demonic shapes would appear - trance during which the woman would be able to predict the future or to become aware of curious details or previously unknown events.

The Court is chaired by Monsignor Bartholomew Sebastian, Bishop of Patti, General Inquisitor of Sicily between 1547 and 1555, known for the modus operandi zealous and harsh stance towards heresies, as well as for having already distinguished himself in his role as inquisitor at the Granada Office, in his condemnation and execution of numerous Jews and Moors. Don Sebastian is sent to the island as a censor of the Kingdom, directly from Charles V, emperor pursuing a violent repressive policy against the Lutherans and the heretics of the Empire, with the aim of fortifying the Catholic faith in Sicily through its most holy mission against heretics, and where the Inquisitor becomes the arm, the direct expression of the Government's policy: the Sicilian Inquisition Tribunal stands out for operating in complete autonomy from the Church of Rome, as an emanation of the Government and the Spanish Inquisition.

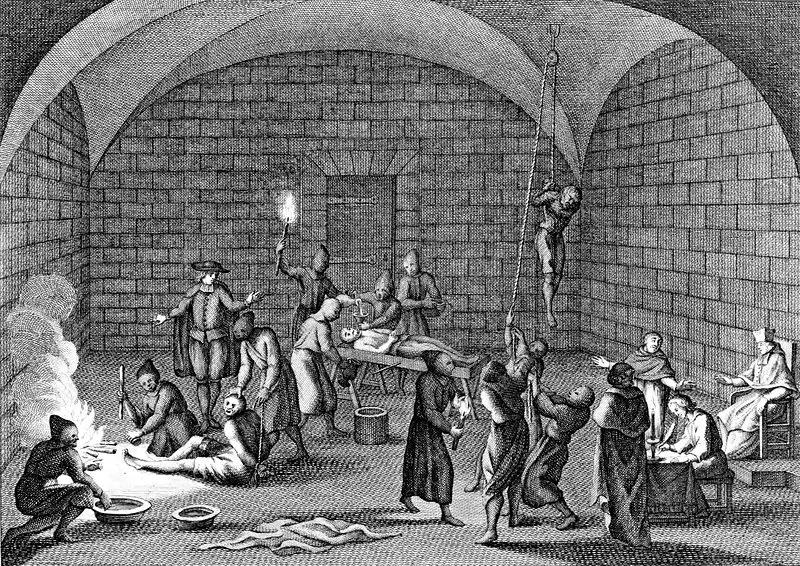

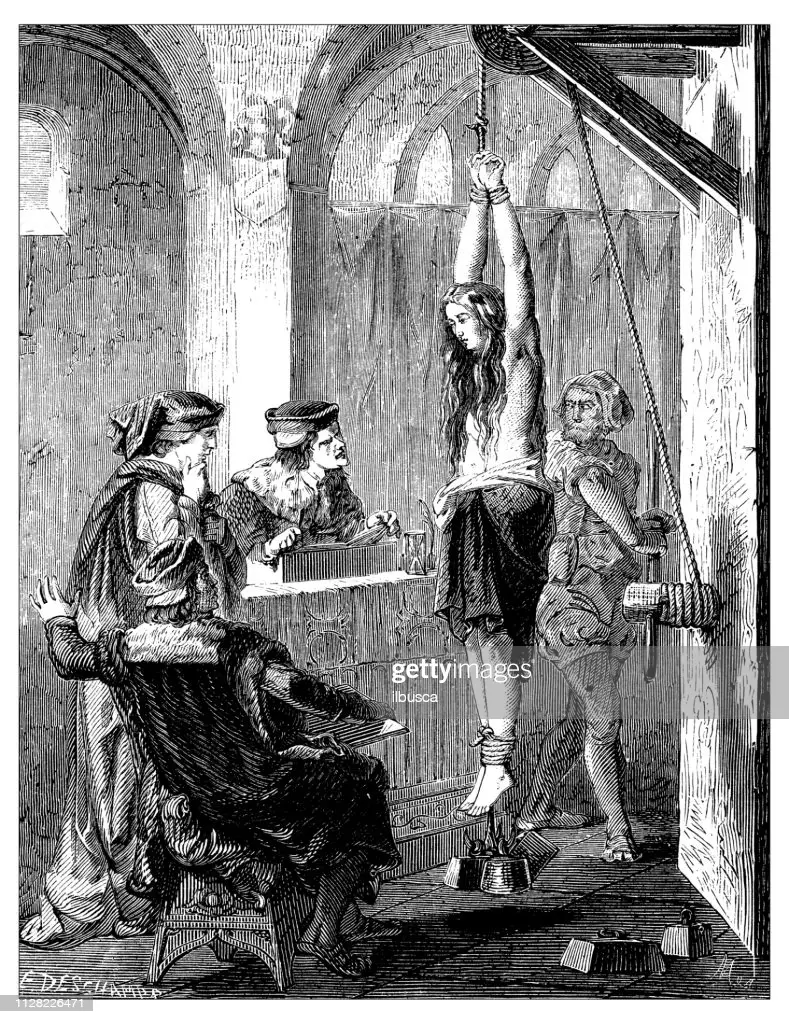

The trial and torture

The process "Super magariam" conducted against Pellegrina (whose documents were collected and analyzed by Charles Alberto Garufi and from Sergio Bertolami) has a duration of forty-two days, relatively short compared to other inquisitorial trials of the time that could last for several years, and begins on April 3, when the woman, summoned by the Court, denies the accusations before the Inquisitor, declaring herself innocent and narrating her arrival in Messina in search of better economic conditions and life with her husband. She cautioned a first time, for having «made asay magarie and invoked them dimonij», the witch is imprisoned due to the statements of the investigators who claim to have evidence on facts that Pellegrina has not confessed, concerning the invocation of demons and the practice of invoices.

A situation that is aggravated by several other testimonies: among others that of having provided a magic bread to a man tortured so that he could not testify, that of falling into a trance while formulating divinations, as well as the preparation of spells of which she is accused by a silk-maker colleague of her husband, who denounces Pellegrina perhaps for his sexual desire towards the woman, which remained unsatisfied. After fourteen days of imprisonment, Pellegrina confesses the scams she committed together with a certain Catherina, who made apparently evil amulets to be placed in the homes of unfortunate citizens (for example wax hearts with pins stuck in) that Pellegrina, informed by her accomplice, found and removed under compensation in money, freeing the houses from the curse with strange prayers and ritual formulas. The accused also mentions a basket seller who approached her to decipher a strange symbol, a sort of "sign of Solomon".

However Pellegrina is taken back to prison after the second admonition by decision of Don Sebastian who, not satisfied with the testimony, perseveres in underlining the connection between the alleged divinatory powers of the accused and the evil one, a proven link, according to the judgment of the Court, from the testimony of two basket sellers who, having lost a ring, turn to the woman to find it, and this, incredibly, manages to indicate exactly who had stolen it and where it was hidden (the finding of lost objects and the identification of the thief is an exquisitely shamanic power, eg. in Siberia and North America). During the period of imprisonment, the Court collects eleven testimonies, against the average of the six usually considered valid and sufficient to issue the final judgment in the trials of the Inquisition courts, all proving Pellegrina's guilt as maybe. The judges then ordered Pellegrina, for the third and last time, to confess the whole truth, having the possibility of obtaining mercy if she proves sensible.

Pellegrina therefore admits the less serious crimes, but denies the heavier accusations regarding the invocation of demons and the relationship with the evil one, probably in order not to compromise her position, and finally chooses to defer to the judgment of the Court. The judges, however, on 7 May, decided to submit the accused to the rope torture (which consisted in tying the wrists of the offender behind the back with a long rope and then hoisting the body by means of a pulley, causing the tearing of the muscles and the dislocation of the arms at the shoulder joint, due to gravity and weight of the body) in order to extract the confession from her.

Three times in the span of half an hour Pellegrina is dropped violently from the beam amidst torments and groans, but she did not confess, addressing her prayers to the Lord and the Holy Spirit and declaring herself innocent. Like this, despite an incomplete admission, at the behest of the Inquisitor Sebastian and the Vicar General of Messina Bartolomeo Cantella, Pellegrina is condemned to the stake during the solemn autodafe (o I serve generalis, literally "act of faith"; solemn proclamation of the Inquisitor's sentence, followed by the public ceremony of abjuring or condemning the accused witch or heretic to the stake) held in the Cathedral Square of Messina, during which the same sentence is inflicted on a Lutheran and eleven other people, including witches, bigamis and blasphemers.

On the same day, however, despite the adverse testimony gathered by the judges, the sentence to the stake is commuted by the Court and Pellegrina is forced to be "publicly whipped for the extras of quista citàWhile he moves in procession along the streets of Messina, with a candle in his hand and a miter on his head, together with other penitents, so that his punishment was a warning for the entire population of Messina: a strong sign of the power of the Inquisition to prevent future acts of maybe and heresies of any kind.

Here is an extract from the chronicle of the trial, taken from the documents and sources collected by Carlo Alberto Garufi in the Archives of the city of Simancas, in Spain. During the interrogations and the torture of the rope, Pellegrina will always declare herself innocent, deferring to the judgment of the Court and, during the torture, addressing her prayers to the Lord and to the Holy Spirit. "And the day of torture came, the XNUMXth of May, without Pellegrina Vitello modifying the protest of those who don't know anything else about who has a finger: - Who knows, who knows pio dirria! - The inquisitor Sebastian and the Vicar General of Messana Bartolomeo Centella still judged it negative in telling the truth and accepting the votes of the ducturi they commanded both to torture the fine line in the meantime whoever tells the truth". The chronicle describes the methods of torture and the Pilgrim's prayers:

Stripped that she was and attached to the rope, she was reprimanded. - Here I am not sacho what to say - The inquisitors ordered her to begin, attaching her to the beam. She crying, she said: - she knew she would tell - she no longer answered the invitations to confess, but she complained. - Ayme, ayme, ha Spiritu Santo mio, ayutami chi non ayo fato nienti, oy Spiritu Santo como non ayo fato nienti, ayutami! - The inquisitor and the Vicar, disappointed by the failure to find amulets and other devilry hidden under their robes, expected him to call his evil Beelzebubs hidden in some clay pot in the house in the San Giovanni district, but the notary Argisto Giuffredi nothing other he could note if not the many times he complained proffering the said invocations.

As confirmed by those who witness Pellegrina's torture, the accused, despite the pain and the pain suffered, continues to declare herself innocent, in fact "witnesses to torture heard her call the Holy Spirit - My Holy Spirit, ayutami chi non ayo fato nienti!"And Pellegrina herself, repeatedly questioned will declare:"The traitors accused me wrongly», Invoking the grace of the Royal Inquisitor and the Vicar present.

To the invocations to the Holy Spirit, he added that to Saint Catherine of Alexandria who had passed through the torture of the easel. She relieved, she hung from the rope and left suspended, she was silent between the inquisitor's invitations to tell the truth ... And she touched and not touched, she said - Spiritu Sancto! She - she was let go, always saying: - Non sacho nienti - Her torture of her lasted the space of half an hour cum ampolleta, without her making any confession.

Witchcraft, textile art and the magical fishing of swordfish

It is interesting to note how Pellegrina's alleged magical art is confused and mixed with the work and commercial activity of her husband in the Messina of the sixteenth century, textile art. The Clavis Siciliae in fact, it occupies a pre-eminent position within the Spanish Viceroyalty of Sicily, in the imperial context of Charles V: home to a dynamic and active port, but also a thriving center for the production and trade of silk, which reaches the markets from the port city of Northern Europe - activity overseen by the "Consulate of the art of silk" since 1520. The silk production process involves numerous layers of the local population, engaged in the working cycle of the precious raw material (cultivation, spinning, weaving, dyeing and embroidery) which, not infrequently, to ensure the protection and successful completion of the silk processing , makes use of both religious practices and rituals related to witchcraft. In this context, the magic (term used to indicate witches in the Messina of the sixteenth century) and, more rarely, nigomari (male wizards), integrated into the community, are active in pronouncing spells, doing or undoing spells, or their presumed gifts of foresight are required - for example, they are required to perform rites in which they declare to foresee possible outcomes and risks related to economic or commercial negotiations.

The story of the maybe Pellegrina Vitello inspired, among others, Leonardo Sciascia for his two novels (one investigative, the other historical), Death of the Inquisitor e The Witch and the Captain, while, more recently, the Inquisition trial of the young woman from Messina provided the basis for a noir story entitled The Witch of Messina, by Antonino Fiannacca (2020).

It is interesting to note how rites and traditions linked to superstitions, knowledge or popular beliefs, albeit of a different nature, they also survive in today's city of Messina, especially in relation to a particular and local work and mercantile activity: fishing for swordfish from the Strait. Once fished with the traditional feluccas, boats that derive from models of the Greek age, the fish is marked with a particular sign called "carded by cruci", consisting of three horizontal and three vertical lines to be marked between the right eye and the gills of the fish as a sign of gratitude towards the animal itself and towards the sea, but also as a sign of prosperity and good omen for future peaches ( but the sign must not be executed by the harpooner). Even the subdivision of the fish takes place in compliance with the functions covered by each member of the crew, from the captain to the harpooner, to the "ferraiolo" who rented the fishing tools, each of which is entitled to a specific part of the catch.

Finally, it is interesting to mention some practices that have fallen into disuse, in vogue until the last century: the use of intoning a chant in Greek (whose terms have survived in today's dialect) during fishing because, according to popular superstition, the fish would be escaped fishing if songs in other languages were used; the custom of having a priest bless the boat due to unproductive peaches that had lasted for some time, when not specific rituals often carried out by the crew members themselves, which provided "magic" formulas and use of potions of various kinds. In the Tyrrhenian belt of Calabria, a Scilla, on the other hand, the curious practice of rung, consisting in making children urinate on nets used for fishing, as a sign of good omen.

“Magare” and “magarìa” in the Sicily of the sixteenth century

In the Messina of the '500 the "real" witches were called magic and they mainly dealt with making or putting on or taking off jets and evil eyes, using in their rituals amulets or fabric puppets to be filled with pins, or peculiar objects such as hearts or symbols in wax, to be hidden in houses to be cursed, such as the heart with stuck pins used by Pellegrina and her accomplice Catherina. To these objects were added mirrors and jugs of water or oil, candles, as well as knots and designs rituals, such as the sign of Solomon or the Tetragrammaton, both referring to the archetype of the Pentacle and the five-pointed Star. The ritual prayers included the vulgarized use of Italian, Hebrew, Spanish and Latin terms.

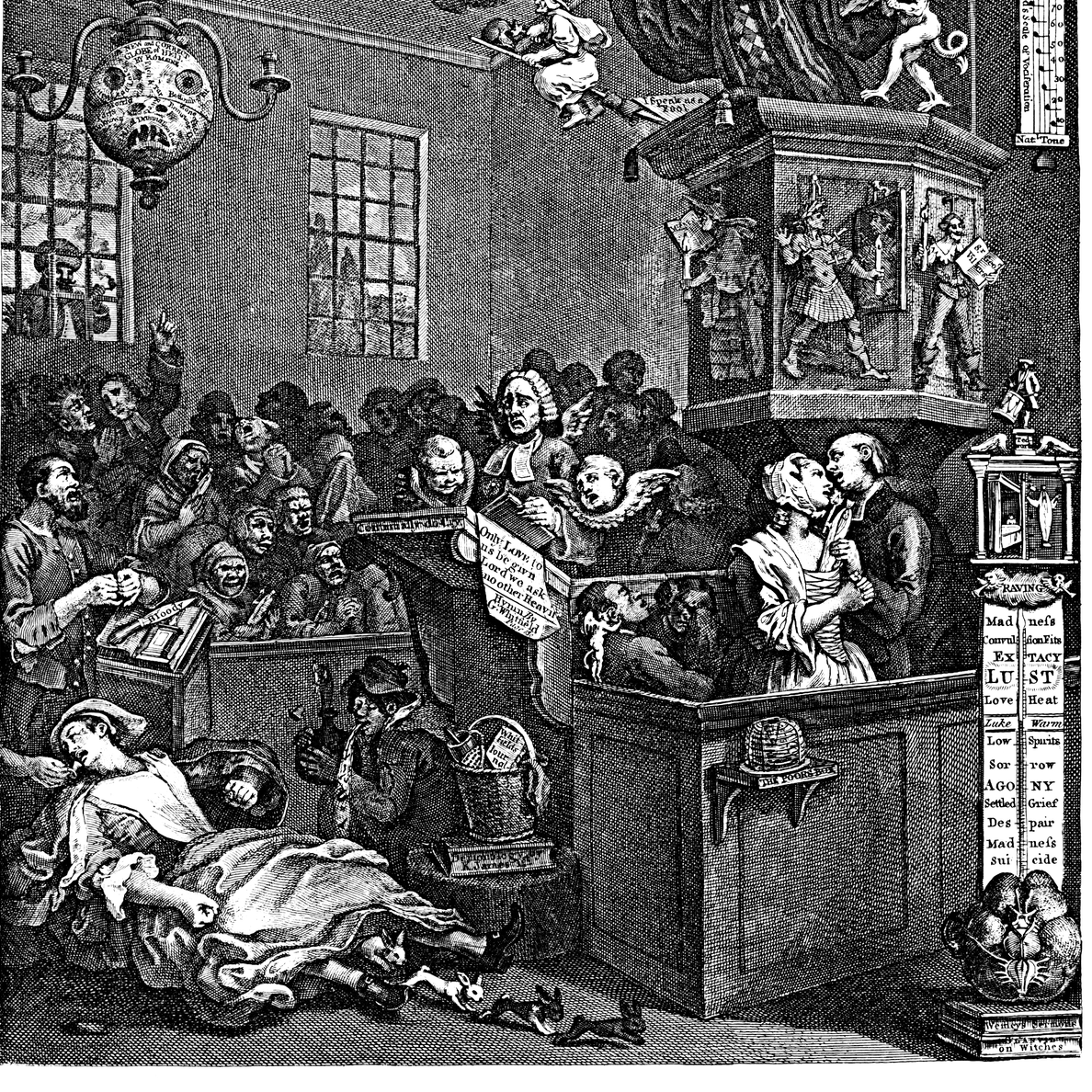

Maybe and sometimes Nigromancers (male magicians), were also consulted to provide love remedies, cures, various medicines, often for contraceptive or abortive use, as well as for find lost items. These women were generally humble, of low social class, slaves, foreigners, however relegated to the margins of the community. Although in most cases the Magare were simple executors of popular traditions or superstitions, the Sicilian Inquisition did not tolerate such practices, especially in the context of the harsh imperial reaction of Charles V, aimed at repressing the heresies and the Lutheran presence of the Empire.

With accusations that often modified and exasperated the reality of the facts, concerning for example the worship of the devil and the invocation of the forces of Evil, the inquisitors proceeded with the incarceration and torture of the denounced Magare. The final sentence of theautodafe it was held in Piazza Duomo and could involve the stake for the accused or an exemplary punishment, such as the barefoot procession or flogging, as happens in the aforementioned case of Pellegrina Vitello. In the event that the witches had been fugitives, the Inquisitors proceeded to burn them in "effigy", or rather to burn a papier-mâché puppet which, symbolically, was to indicate them.

Bibliography:

BERTOLAMI, SERGIO, Domina nocturna. An inquisitorial trial for witchcraft in sixteenth-century Sicily, Experiences, Bologna, 2008.

FIANNACCA, ANTONINO, The witch of Messina, publisher Antonino Fiannacca, Ebook, 2020.

GARUFI, CARLO ALBERTO, Facts and characters of the Inquisition in Sicily, Sellerio, Palermo, 1978.

SCIASCIA, LEONARDO, Death of the inquisitor, Adelphi, Milan, 1992.

ID., The Witch and the Captain, Adelphi, Milan, 1999.

On the traditional swordfish fishing of the Strait of Messina see: https://www.colapisci.it/Cola-Ricerca/Luoghi/Ritualipescespada.htm ; https://culturalimentare.beniculturali.it/sources/pesca-del-pesce-spada-nello-stretto-di-messina ; https://ilcalicediebe.com/2018/08/07/scilla-e-la-tradizione-del-pesce-spada/