In many legends of Italian folklore the mandrake inhabits the waters and is interchangeably described in its triple plant, zoomorphic, anthropomorphic aspect. Here we will describe some particular convergences between the "monster-mandrake", some mythological and non-mythological reptiles (salamanders, basilisks, snakes, dragons, reptiles and amphibians in general, winged creatures) and some subterranean and liminal creatures of the various legends such as spirits, goblins, premature deaths, damned souls.

di Gianfranco Mele

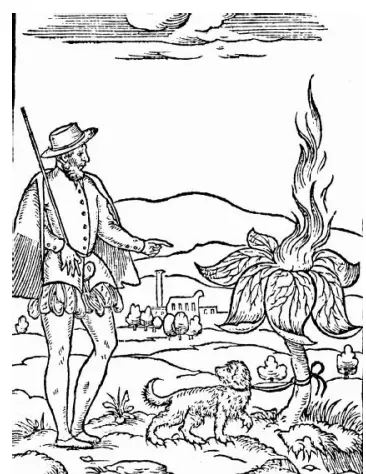

cover: Salamander crowned in the flames, 1548,

trademark of a printing house

I draw part of these lines from my work from the title Storm Solanaceae published in Elsewhere (SISSC yearbook) n ° 21 [1]. In that case, however, I had focused my attention on the fame of stormy plants, attributed by myths and legends of various cultures, to a series of Solanaceae tropanics (Giusquiamo, Datura, Belladonna, Solandra, and finally the Mandrake on which I return in this article) [2]. In many of these legends, even the mandrake inhabits the waters, and is interchangeably described in the triple plant, zoomorphic, anthropomorphic aspect. Here, we will return not only to these characteristics attributed to mandrake and on the curious definition of "Water monster", but also and above all we will describe some particular convergences between the "Monster-mandrake", some mythological and non-mythological reptiles (salamanders, basilisks, snakes, dragons, reptiles and amphibians in general, winged creatures), and some subterranean and liminal creatures of various legends such as spirits, goblins, premature deaths, damned souls. I owe much of this latest information to the extensive research conducted by Alberto Borghini, which I will quote often.

But let's start with the beliefs about the mandrake as an “aquatic monster” and therefore about its interchangeable plant and animal aspect. Remo Bracchi informs us that in Bormio, in the province of Sondrio, to prevent children from getting too close to the waterways with the risk of being dragged away by the whirlpools, it was warned that in the noisy sinkholes the mandràgola, a frightening monster that would leap from the waters and devour them. Likewise, in Morignone, where the mandrake is described as "a river dragon", The elderly recite the nursery rhyme to the children:

«a l'Ada, marcina, as mai dir atórn, che l vegn la Madrágula, cu cresc'ta turchina, cu bóca de fórn, che la ve inguìda ghió».

("Little girls, you must never go near the Adda, because the Mandrake lies in ambush among the whirlpools, ready to suck you into its jaws in a single bite")

[3]

The monster-Mandrake was also believed to be present in the water of the fountain in the center of the town, and one could be captured by it by climbing the banks. Also in Trepalle (fraction of Livigno, also in the province of Sondrio), it is believed that the Mandragola hides near the point where the stream becomes more impetuous [4]. Also in those neighborhoods, in Frontale, the mandràgola is a monster "that lives in the eddies of the stream", a sort of dragon that feeds on the flesh of children [5]. In Grosio a similar representation is designated with the name of marantula (other variant, maramantula), imaginary animal "present in fountains and waterways, evoked to warn children against putting themselves in danger on the embankments of the pebbles" [6]. In a legend of Lake Garda, the mandrake is a female figure who kidnaps young people and hides them at the bottom of the well [7].

The mandrake-water monster shares traits common to a series of imaginary creatures of popular tradition and mythology. In a series of Italian legends, in fact, water monsters are found mostly linked to female personifications and united by similar characteristics (they live in wells, they are greedy for the flesh and blood of the children who suck into their aquatic lairs), from names similar: in the south, in Campania Maria Catena, Maria Catena, Maria Crocca, Maria Scissors, Maria Longa [8]; in Sicily Marrabecca, Mother Rhebecca, Mamadraga. In Veneto the Marantega is identified in the Befana but also in one "scarecrow for children"That"it is said to be in the well and in the ditches" [9]. This figure has been identified with the ancestor of the Lares (Larunda) [10], and would derive in any case from the Latin Mater Antiqua, corrupt in the dialect Sea Antiga [11]. One cannot fail to notice the affinity of these figures, and even of the names (especially in the case of the "Maria Catena"Bell), with Marica, ancient goddess of waters and swamps, and with the term of pre-Indo-European origin mara = waters, marshes, swamps [12]. With the Mammadraga Sicilian (also described in the Tales of Pitre) we are even at the correspondences / mergers between female water monsters, the cited “Mater Antiqua”, and the “dragon”.

In Livigno (another municipality in the province of Sondrio) they are used to define the monster that inhabits streams, both the name mandrake is salamandra [13]. Also in Friuli, the salamander is designated by the term mandraule, and it is believed that "when the salamanders rise towards each other, the rain will come; if they descend, the clear sky returns or lasts» [14]. The salamander-mandraule it seems to have here (and in various areas) prerogatives in common with the mandrake-plant. The overlap between the mandrake-salamander and the mandrake-plant is recurrent in various localities and is characterized in terms both of a fusion between the characteristics and the appearance (or transformations) of the plant and of the animal, and of the merging of properties and common magical uses: for example both are attributed magical-aphrodisiac properties (which were also attributed to them in ancient times), both have the power to unearth hidden treasures, and both are linked to rain, even where there is distinction between the animal and the vegetable creature [15].

Like the mandrake, the salamander is closely related to thunderstorms and rains [16], and already for Pliny the Elder the salamander is «animal with the appearance of a lizard, spotted, which never appears except together with heavy rains and which disappears when the weather is clear» [17]. In Northern Italy the popular name of the salamander is "rain snake"; in the southern dialects "water lizard"; in Piedmont and Friuli it is also called "rain"; again, in Piedmont the salamander is also called "Barcara"(In reference to the boat); in Maratea (Potenza) "dipper". In Lunigiana and in Garfagnana it is believed that the salamander falls from the clouds along with the rain; in the province of Pistoia it is believed that if you kill the salamander it will rain for 40 days. In the Canavese area, salamandre are associated with the floods of the stream, and in the province of Vercelli they are called "water dog"; according to other testimonies the salamander "it is a kind of lizard that only comes out after summer storms" [18]. Still, in the province of Treviso "the mandrake is a species of lizard about forty-fifty centimeters long, brown and yellow in coloro" [19], in Tuscany "mandrakes ... they are like lizards, yellow and black, ugly" [20].

The salamander is also related to fire and magic. It was thought that she lived in fire, that she had the ability to make flames alive and also to put them out [21]. In some ancient representations is wrapped in fire or breathes fire (like dragons and basilisks). A link with fire is also given by the poisonous properties attributed to the salamander [22]. From a magical-esoteric point of view the salamanders were the elemental spirits of fire, and for the alchemists they are (precisely because of the ability attributed to these animals to resist fire) a symbol of calcination. It was believed that they could rise like the phoenix from their own ashes, that they inhabited the volcanoes emitting cries, that they could speak, reveal secrets, and that they accompanied the witches [23]. Here too we notice affinities with the mandrake, both generically for the great magical qualities attributed to the plant, and with respect to the poisonous properties in common, to a series of elements such as the cries (also the mandrake "screams"), the keeping of secrets, and the association with fire: according to some legends "the plant radiates fire","it looks like fire","and hot”, And“fire and “heat”Also refer to the potency of the plant's poison and its effects.

This "fusion" of the mandrake with a reptile and / or with an amphibian often returns: for the mountaineers of the province of Massa Carrara, the mandrake is a reptile resembling a small winged dragon:

«The mandrake up here is a kind of animal; it didn't fly but it had some kind of wings. It might have looked like some kind of dragon but it wasn't big, it was about fifty centimeters. And one said, "Oh my God, I've seen the mandrake!". And they said she was bad but maybe he was more afraid of them».

[24]

Even according to the story of a man from the Trompia Valley (Sarezzo), in the province of Brescia, the mandrake is «an animal, a kind of lizard» [25]. A Venetian woman (from Volpago del Montello, province of Treviso) says that the mandrake "it's a kind of lizard", And links its presence to thunderstorms:

«The mandrake is a species of lizard about forty to fifty centimeters long, brown and yellow in color, and comes out only after summer storms. Never seen in winter; in summer, during the day, but only after thunderstorms. It also sucked to see him».

[26]

Borghini dwells a lot on the theme of transposition of the term "mandrake" to animals (salamander / basilisk / flying dragon) It is on transfer of typical prerogatives of the mandrake-plant to the mandrake-animal (reptile) and vice versa. Also in Val Trompia, another informer from Sarezzo states that the mandrake is an animal, but "a kind of bat"[27]: here we are far, notes Borghini, from the attribution of reptilian characteristics to the "mandrake", but we still remain as part of the "winged": that is, in the "surrounding" of basilisk / flying dragon [28]. In Friuli, as well as mandraule, salamandra it is called mazaròc. The latter is also the name of a goblin-ogre (devil) of Venetian folklore [29].

Borghini sees various connections in the beliefs on mandrake-salamander-goblins-basilisk. See also my contribution in which I focus attention on a series of common characteristics between elves and the mandrake plant. [30]. Moreover, i cunfinacc of Valcamonica, the people confined and buried in a liminal area (in which mandrakes grow), are the restless spirits, the damned and the prematurely dead, not comparable to the deceased "domestic" [31], which recur to the living in hallucinatory forms and are characterized by malevolence and by works of damage and destruction towards the community. In other words, they are similar to larvae Roman, to a series of spirits that re-manifest themselves in the guise of little monsters-goblins in popular tradition (eg. the "Laùru"Salento), and with the mandrake-anime or animated they share a whole series of traits.

In Monno, a particular story is told. The mandrakes come alive, in the guise of carnival masks. These beings enter the stable of a family's house, do some caciara, then go away but one of them remains there as if lifeless. She is taken and buried in a field, which becomes her grave and the field of the mandrake, "the grass that calls water"

«In the stable of poor Fraine (a deceased man), a company of foreign masks arrived on the last evening of Carnival. Three held each other by the arm and the others followed. The three sat down. They made four jumps and two antics and then they all disappeared closing the barn bolt from the outside. Those inside noticed that they had forgotten a seated mask, but could not chase them right away because they were locked up. Then the swiftest ran after them through the hole in the barn. But he couldn't reach them. The mask was buried in Pridicc, the Melotti meadow, and when they mow over her grave it always rains. It is the mandrake, a bad herb that calls water. And when they mow in Pridicc, and then they have to dry the hay, it rots for sure».

[32]

Another similar story, always coming from Momo:

«Once, at Carnival, in the stable (of the Fraine family) they found a dead mask, they buried it in Pridicc and made a plaque with the painting of a mowing mask (symbol of death) and there was the date of when they found her dead. When they mow it rains and the mask is called mandrake».

[33]

The "mask" is buried in one area extra lemon [34]; in fact, the creature is part of those confined souls, not deserving of receiving ordinary sacraments and burials. Here, the long-standing theme of the mandrake seen as a damned soul or expiant or awaiting redemption reappears: in the commentary on the Song of Songs, written by Philo of Carpasia (between the end of the XNUMXth century AD and the beginning of V), the mandrakes mentioned in the Canticle itself are "the dead buried in Hades awaiting the resurrection". Even Matteo Cantacuzeno, commenting on the Canticle, says that the mandrakes "they mean the souls of Limbo and Purgatory, because these souls lie like the Mandrakes buried in the bowels of the earth» [35]. Same thing claim a number of later commentators [36]. The mountaineers of the Parma Apennines say that the Mandrake «has a soul","it has the shape of a baby in swaddling clothes, and is produced by an infanticide committed on the spot» [37]. Moreover, since ancient times the mandrake has been represented as an anthropomorphic underground being, endowed with a soul, capable of emitting sounds (the mythological "scream" of the eradicated mandrake), and even animable, in the condition of homunculus, once unearthed by magical procedures.

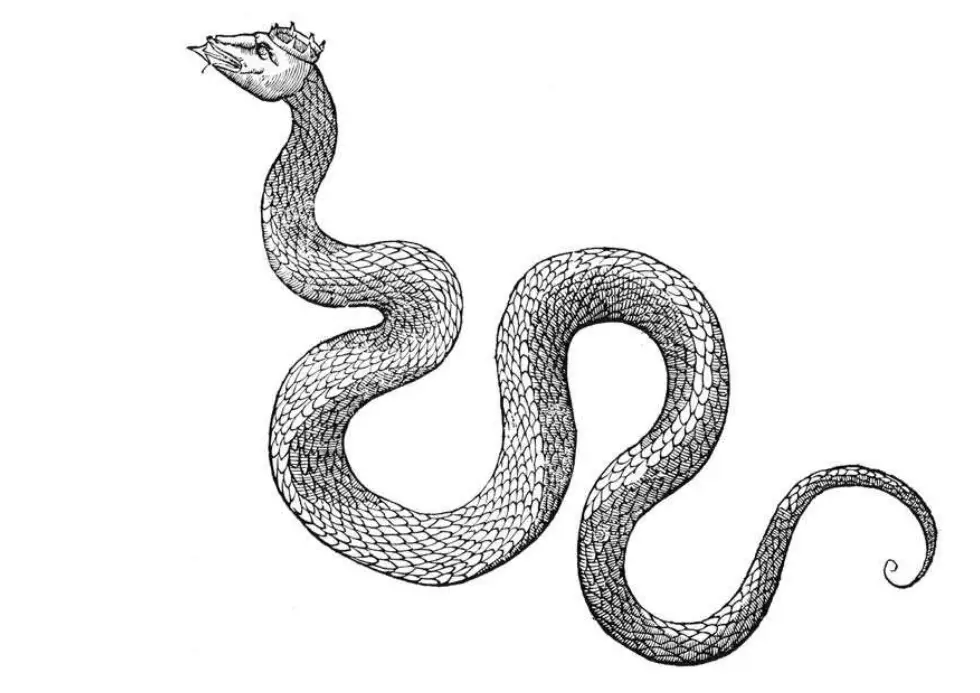

But "a baby in swaddling clothes"Is also the basilisk, in the attestations of various interviews conducted by Borghini [38] : is "something that looks like a baby in swaddling clothes"and "it could have been the Règle"(Serpent Regulus), is"the Biscio Bimbin who was on the ground [...] and they said he had a baby's head" [39], is "a scaly animal such as a large snake, in the lower part, and in the upper part a child"And is also called"biscio basilisk" [40]. Again, a detailed description collected by Borghini in 2002 in Gorfigliano (Lucca), through the voice of a 64-year-old local:

«... they said that there was a biscio, in short, the old people always said it, that it wasn't that long, but it was big. In those days, babies were swaddled with swaddling clothes, and gave the impression of a baby in swaddling clothes, they said he was stocky and big, in short, he wasn't long; they called him the "biscio bimbin". One day a hunter was there, at that time they were cutting the hay, and he saw this snake, he was going to shoot him, there was a woman there, he was around the hay, and he said: "Don't shoot him he is a" bound soul " (relegated). It is a fact that I have always heard. My grandfather told it, my grandfather was from 1882, he counted it, he says he knew what he wanted to shoot».

[41]

In this story, other elements in common between the basilisk and the mandrake appear: the appearance during the haymaking activities [42] and the common feature of "relegated souls". A further element of convergence is in crying: come on the uprooted mandrake screams, cries, so the basilisk was "a little boy crying, it seemed, but he was a snake, a snake" [43]. Here, in the weeping of the mandrake and the basilisk, there is also a convergence with the weeping of the elf: the “laùru"Salento, for example, cries bitterly if his hat is torn off (a recurring story in every folk tale about the creature), but above all, and in more elaborate and detailed" testimonies ", it is a restless and restless soul that manifests itself ( with the likeness of a child) crying continuously with pain for having left this world too prematurely and / or without having received the sacraments: in the case of Lattanzi's story, for example, the elf who manifests himself to a family from Bari is none other than the restless and tormented spirit of "uncle Ettore", who died suddenly due to a bad illness and buried without the family having had time to assure him the sacraments [44].

In the Alpine area the basilisk is "a crested viper with the head of a child", And this crested viper"flies, it is a kind of dragon with a red crest, flying from top to top", and "there is also this fear of finding her at home when they bring hay" [45]. In Val di Susa we talk about "vipers, snakes as big as a child, a swaddled baby", And in Friuli the magna (local name of the basilisk) has the face like a child and is also linked to atmospheric change [46]. In France, in the Poitou region, the mandrake is a snake, and represents the devil; he procures wealth, doubles the number of coins placed next to him, and he is an infernal and cursed being: whoever is his friend or has him will be happy in this world, but unhappy in the next [47]. More generally, it is widely believed that whoever owns and keeps a root of the mandrake plant will be lucky, and the mandrake will be able to provide him with wealth, prosperity, and fulfill any desire of her.

Underworld creatures that find or guard treasures and riches are also snakes and goblins. The snake in many legends guards treasures, even attributed to it "a kind of bright eye that shines in the night"(A kind of diamond, of"tomato"Etc.) which brings wealth and luck [48]. The same mandrake-plant generates golden apples, and is believed to shine at night like a lamp: "glitters","goes the little light","it's bright”, Several legends state. Even the mandrake in Austria is a winged reptile laying a golden egg. The Serpente Regolo in Alta Garfagnana has in mind "something like a diamond", A"little star", A"yellow crossa "that looks like"to a colored diamond that glitters against people" [49], as for Pliny himself, the basilisk has a spot on its head "like a diadem" [50]. According to some Abruzzo variants, the snakes have on their heads "a magnet”Which brings luck to those who manage to get hold of it, and use it as a ring or pendant. In Friuli this lucky charm is called "the apple of the biscie", While in Verona the powerful talisman is the very skin of snakes, the"shirt of bysso" [51]. Borghini and Toro note another series of common attributions to snakes and mandrakes in popular beliefs, such as the ability to cure sight and stomach ailments and, again, promote menstruation and childbirth. [52].

I will not dwell here on the various and well-known legends that surround the goblins in the folklore of every place, as beings themselves guardians of treasures, and able to ensure wealth, happiness, prosperity and protection to anyone who came into contact with them, is considered worthy and "friend" on the part of these creatures (otherwise, they will manifest themselves with hostility and causing spite, discomfort and misfortune, therefore in the context of an ambivalence, here too, common to mandrakes and snakes). The elf is often also attributed with the power of fascination (also in its assonances or character traits common with satyrs, genii cucullati, in its connotations panic e priapic) [53], another element in common with the basilisk and snakes in general [54], and we will talk about this later, analyzing a singular, ancient painting of the Messapian era.

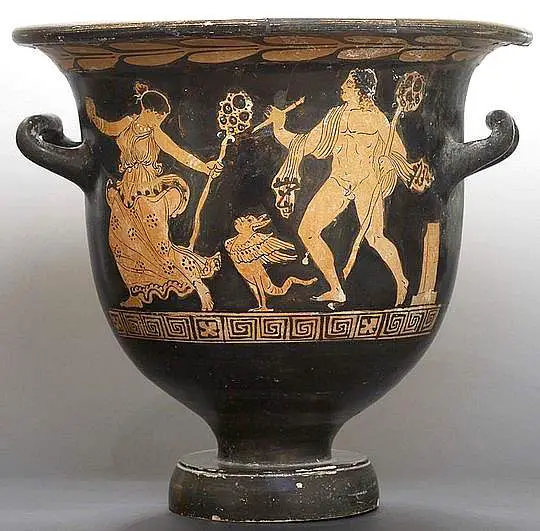

Thanks to a study by my friend Oreste Caroppo, a researcher from Salento, a particular representation leapt to my eyes: in an Apulian red-figure vase (about 350-326 BC), preserved in Lombardy and probably coming from a Messapian tomb in the territory of Squinzano [55], a naked man, a maenad and, in the center of the painting, a monstrous creature are depicted (from the description of the find :) "... bipedal, with reptilian body, long tail, deformed face and feral ears; the monster is without comparison in the iconographic documentation".

In his analysis, Caroppo associates the figure with chameleon-basilisk from Salento: in fact and as per the description in the card, being is a mixed anthropo-zoomorphic with some characteristics of reptile, others of volatile and others human, a sort of little ogre-elf. The being also seems to cross its gaze (almost to "fascinate" it) with that of the maenad, who, according to the interpretation given in the card, runs away or tries to escape. The fascination is a feature attributed to basilisk, in Salento al fasciuliscu (Melli dialect term designating the basilisk, but according to Caroppo it refers precisely to the Salento chameleon [56]) and even to the elf himself.

This is not the place to investigate the controversial presence of the chameleon in Salento: there are those who want it "naturalized" [57] recently, even around 1983, who instead highlights the fact that, and in any case, already in the Salento of the seventeenth century. the Mediterranean Chameleon was portrayed with particular wealth and knowledge of the creature, in some sculptures (Palazzo Lanzilao, Lecce) [58]. The fact is that this animal, presumably imported several times over the centuries, perhaps even millennia, has had to somehow strike the popular imagination. [59].

Returning to the Apulian vase probably of Squinzanese origin [60], I wouldn't swear it really depicts a "chameleon-basilisk". However, what is surprising looking at that representation, described by experts as "without comparison in the iconographic documentation" [61], is the convergence, the fusion of this strange and singular little creature with a whole series of characteristics described by Borghini in his tracings of the correspondences between (at least) basilisk and elf, and more generally a winged monster similar to the various creatures described so far. In a sort of brain-storming carried out against people who did not know the work and who viewed it for the first time, I was able to find various and convergent descriptions (with each other and above all with the monsters described in the researches cited so far): "Basilisk", "goblin", "winged goblin", "bat", "little bat-man", "winged child-animal", "winged dragon", "winged man-mandrake", etc. etc.

Here, in what may be the "syncretism" represented by the little monster in Squinzano's painting, we therefore return to the question of the sharing of characteristics between mandrake, reptiles, amphibians, winged creatures, birds, goblins etc., already described above, and to which I return by citing some other passages of Borghini's research:

"...always for the elf, images of winged wings such as the bat and the tawny owl or the barn owl are evoked; or rather we speak - remaining generally speaking - of a nocturnal bird: all elements which, if compared with the elf-reptile, will appear to be framed in the combination / alternation, in the composition / decomposition (which - we know - is the salient characteristic of the basilisk) of 'reptile' , on the one hand, it is 'winged', on the other.

The claims are quite numerous:

“The Buffardello is like an animal, a bat, but red; goes around at night and enters houses and stables. It makes the braid in the tail of the cows and it must not be untied otherwise it is bad ”(Treschietto).

“The Buffardello is like the locco (ie owl), a nocturnal animal, a bird. But it has the pointed ears of a bat; enters the stable and braids the horses' tails ”(Caprio).

“The Bafardéll is a beast, like the locco or the barn owl, it flies, goes out at night and goes to the animals; however, there are hardly any more ”(Casarola).

“The Bafardélo is like a nocturnal bird, but there are hardly any more. He is not bad, he goes to the beasts locked in the stables; he is able to manage cows and bring mares to drink "(Comano).

“The Bafardéll hides where it wants and becomes as it wants; we saw him, at times, that he was like a dark scroll that turns, like a vortex that goes strong, very strong, we saw him crossing the street and slipping into the stable; or he could become like a nocturnal bird and even in this form he entered the stable. Then there, at night, he would take the look he has when no one sees him, like a little man, and start combing the mares ”(Monchio delle Corti).

Thus in Garfagnana:

"In Minucciano some also claim (speaking of Buffardello that is) that it is a species of nocturnal bird, with two horns on its head, which sometimes "can be heard breathing" inside the town tower».

[62]

In Borghini's work, to conclude with the correspondences between basilisks-salamanders-reptiles-amphibians-birds-bats-goblins, there are other important elements to underline. In an Alpine area report, magicians-illusionists deceive people by showing non-existent things. For example, the real vision of a hen pulling a thread of grass towards her is transformed into that of a large trunk dragged by the animal; only a woman who had a pannier with her [63] in which he was a viper escapes the illusory vision, because this reptile gives it the power to escape from spells and deceptions. This tale appears to be widespread almost everywhere with slight variations; in some versions the animal "protector" from visions is "a snake", in other "a toad","a frog", in other "a lizard". Among the numerous variations, in an area of the Alta Garfagnana is a winged snake (according to Borghini, with all evidence, the basilisk / ruler). In a French attestation of the La Hague area it is a salamandra. More generally, in some areas of France it is handed down that the salamander "a le pouvoir, pour celui qui le porte, de dissiper toutes les illusionss ” [64]. In an area of the Parma Apennines, the same story as above has a variant the presence of the elf instead of the viper and of the other animals mentioned so far. More, in that area, the elf joker “Can transform in a salamander".

Il joker, as the Laùru Salento and other elves of European folklore, lives in the stables, makes braids for horses, but (its peculiarity) he goes often at the fountain and there, when he hears someone coming, it can turn into a salamander. Also for this, “After midnight, you should never drink at the fountains because spirits enter the body" [65] (and here the theme returns, as well as correspondences and transformations, of the fountains-wells inhabited or frequented by these fairy creatures).

In some areas of the Apuan Alps, the local folletto, the Linchetto, manifests "in different forms, even as a snake". The Samburlet of Pinerolo it can transform into a lizard instead, it's a "lizard"Is also the Sarvanot, "Elf of the woods" of Val Maira in the province of Cuneo. Still, in the area of Cascio di Molazzana (Garfagnana) the Buffardello would have semblance of "foionco", which would then be a "flying snake" [66]. The correspondences between elf and basilisk (also in the galliform representation of the basilisk typical of the Middle Ages), are also reflected in the figure of the Mazzariol (Istrian elf) who has "the body of a small man, with a cockscomb, spurs on his feet and a red cap on his head" [67].

In some areas of the Venetian Pre-Alps the mocking ogre it is confused with the elf-massarol o mazarol, and can assume appearance of basilisk. Moreover, often orcs, fairies, basilisks and goblins not only do they live together in the same habitat, but "cooperate" with each other, as evidenced by a suggestive story reported once again by Borghini [68].

We have already mentioned the similarities between the "luminosity" attributed to the mandrake and the basilisk (the snake / ruler with luminous eyes), and we have also mentioned the power of fascination (through the gaze) attributed to both the basilisk and the elf. He writes about the basilisk Alberto Garobbio:

« It is a little larger than a green lizard, and it also resembles it, although its skin is not green but dark gray and covered with scales. On the head it has a horny crown, along the line of the back and on the tail a very hard saw crest. On the sides, two membranous wings sprout which it opens flying like a bat. Pushing out his bifid tongue, he whistles and draws the attention of men and animals. Whoever looks at his little green eyes is enchanted and remains as if he were a stone. Not a foot can move, nor a hand, nor lower the eyelids to escape the curse, nor scream for help. The venom of the basilisk rooster takes effect immediately and there is no escape; the damned beast, however, waits to bite the victim who cannot escape, stopping to stare at her for hours, enjoying the desperate terror and shortening the torture only if he hears someone approaching him. Whole woods and flourishing farmhouses sometimes catch fire and in the blink of an eye fall prey to flames. It is the basilisk rooster who, flying ominously, dropped a drop of the poison. The horrid beast is said to be born from the egg of a seven-year-old rooster, hatched by the rooster for three weeks».

[69]

In this testimony collected by Garobbio about the power of the basilisk's gaze, references to the bat, as seen. Sempe about the gaze of the basilisk, says Remo Bracchi:

"...it leaps at man with prodigious leaps, spraying poison and chasing those who flee; he blows like a cat and sometimes emits frightening whistles, which drive the cattle on the pasture mad. The fascinating power of his gaze is dangerous and even deadly; the basilisk offends: it stuns the prey, enchants those who see even from a distance; whoever is struck by his gaze loses speech or dies; if he is the first to see others, they die immediately, if instead others see him, it is he who dies».

[70]

Well, a strong fascinating power is also attributed to the goblin's gaze, as per a series of testimonies collected by Borghini (this one, coming from Tavernelle (PG):

«I heard it every night, I heard the hooves of the horse going to the fountain, but I didn't look out because it is better not to be seen by the elf, if you meet his eyes you don't know what can happen».

[71]

In the province of Massa, the moustache with his "keep an eye on"Can cause the same damage typical of people carrying the evil eye towards animals and people, in this case making a cow lose weight and stop making milk. In the case of the tale in question it is not a "traditional" evil eye but something similar:

«The Bafardélo is not bad but if a cow becomes unpleasant for her it is over. When a cow begins to lose weight or no longer gives milk, it is said that the Bafardélo keeps an eye on it. I had a beautiful one, the fattest in the country and she gave so much of that milk that I envied her. Then, she began to lose weight suddenly, and she was not giving any more milk. It will be the evil eye, I thought, and I went to the healer to make the dish. She, if she saw that there was evil eye, she marked with the silver band, made three crosses three times, said the words and then father and glory. But first she had to do the dish to see if the three drops of oil in the water made snakes. She made the dish and nothing, the oil always remained intact. There is no evil eye, she said, you will see that it is the Bafardélo who took it badly.»

[72]

In Mossale, in the province of Parma, a feature of the elf is its gaze: "I've heard about it from many, there was also someone who claimed to have seen the goblin, red, and with the bright eyes of a spirit» [73]. In another area of Parma, in Rigoso, the Linchetto has "eyes as bright as burning coals"

«She saw it one night, she heard some noises in the kitchen and she went to see because my mom was a brave woman, she took an iron and went slowly to see. He opened the kitchen door and, near the stove, he saw the Linchetto, it must have been forty centimeters tall, with pointed ears and eyes bright like burning coals, he saw it for a moment because then the Linchetto immediately came realizing that he was being spied on and then he quickly ran away from the window, passed through the crack through which the air enters. After her, my mom was afraid that she might hurt her, because she looked at him, and then she called the priest to bless and put a red cloth by the window».

[74]

Once again, therefore, the singular assonance between all these common characteristics attributed to the various beings described up to now, and the representation present in the Apulian red-figure vase of the fourth century BC, that kind of winged goblin with reptilian tail that stands between the maenad and the crowned young man, and seems to want to fascinate the maenad.

Before stopping, I will briefly point out additional associative elements among a series of figures described in this article.

In some areas of Valtellina the "basalsk" is a dragon with bat wings and a rooster's head [75]. In Val Gerola it is said of a terrible power in whistle of the basilisk, capable of killing [76] (so that you have to get away, flee by covering your ears well to avoid the deadly consequence): which is more than evidently reminiscent of the deadly powers attributed to the scream of the extirpated mandrake, and the part of the ritual consequent to the extraction which consists precisely in moving away by covering one's ears, and also the powers of the cry of the salamander described above ). The basilisk is sometimes identified as a species of toad ("sciatt basalisk"), A" big toad with a long tail "or" a snake with a toad's head ", emitting a terrible sound and poses a serious threat to children [77].

Summarizing the main correspondences:

- MANDRAKE :

- It is also called salamandra.

- It is related to rains and temporal.

- It is a aquatic monster.

- It is a dragon.

- It is a reptile or amphibian.

- È winged.

- He cries.

- Urla if eradicated e you have to plug your ears in order not to die.

- Fa find treasures, keeps secrets.

- È poisonous.

- È flaming.

- It has properties aphrodisiacs.

- È a baby in swaddling clothes.

- It's a'damned soul or the spirit of a dead man without sacraments.

- Appears during haymaking activities.

- SALAMANDER :

- It is also called mandrake.

- It is related to rains and temporal.

- It is a aquatic monster.

- It is a dragon.

- He cries.

- Urla.

- Fa find treasures, keeps secrets.

- It is poisonous.

- È flaming (breathes fire).

- It has properties aphrodisiacs.

- DRAGON :

- It is a salamandra or a mandrake or serpente.

- It is a aquatic monster.

- It holds secrets.

- È poisonous.

- Spit fire.

- È winged.

- Ha the cresta.

- GOBLET :

- He cries.

- Fa find treasures.

- È a child.

- It's a'damned soul or the spirit of a dead man without sacraments.

- With the look fascinates.

- È a kind of bat.

- È a basilisk.

- È a nocturnal bird.

- It can turn into a lizard, snake, flying snake.

- Ha the body of a little man, With the cockscomb, foot spurs.

- BASILISK :

- It is related towater and rains.

- Whistle and you have to plug your ears in order not to die.

- Fa find treasures.

- È poisonous.

- È flaming.

- È a baby in swaddling clothes.

- With the look fascinates.

- Born from a rooster egg.

- È winged.

- It is a serpente.

- It is a dragon.

- It is a toad.

- Ha the cresta.

- Ha small membranous bat-like wings.

- It's a'soul relegated.

- Appears during haymaking activities.

I must conclude with a consideration: what is explicitly and recurrently highlighted in Borghini's writings is (his words) "complex series of relationships”Among all these beings described up to now. I confess that several times, scrolling through the writings of both Borghini and my friend Caroppo, and not least this mine with my further additions and digressions, I thought that such correspondences and such complexity cannot be other than the fruit of an enthusiastic visionary transport in search of such intricate convergences. I would not mind it equally, if it were so, indeed, this effect would only be the confirmation of the burlesque, fascinating and fascinating, suggestive, bewitching powers of this series of creatures in our imagination.

Footnotes:

[1] Gianfranco Mele, Storm Solanaceae, in "Elsewhere" n.21, Nautilus Edizioni, 2020, pp. 142-169

[2] The recurring link is that of being defined as plants "that carry water", that "they bring thunderstorms", Which cause"wind, hail, storms”: There is therefore a frequent association with water and atmospheric perturbations.

[3] Remo Bracchi, Names and faces of fear in the Adda and Mera valleys, De Gruyter, 2009, p. 91

[4] Ibidem

[5] Remo Bracchi, op. cit., p. 93

[6] Remo Bracchi, op. cit., pp. 93-94

[7] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, Mandrake, salamander and reptiles: elements of correspondence, in “Lares”, vol. 76, n ° 2 (May-August 2010), p. 130

[8] Also said Longa hand and in this case represented as an enormous, very long and monstrous hand that would have dragged the children who leaned over it to the bottom of the well. Analogous representation ("Manu Longa","Black Hand”) Is in the Apulian tradition.

[9] Dante Bertini, Singing and cantàri. Poems in Venetian dialect with a glossary added, Quaderni di Poesia Ed., 1931, p. XIV

[10] AA.VV Tridentum vol. 3-4, Bimonthly Journal of Scientific Studies, Stabil. Tip. Zippel, 1900, p. 135

[11] Various correspondences with the Germanic and Slavic folklore monster called Sea. Also in this case it is a (originally) female mythological figure whose main characteristic is riding the chest of sleepers: it is also a figure associated with horses, whose manes are also woven. Here, the correspondence is above all towards the goblins we are talking about in the course of this article, while from an etymological point of view one could glimpse a similarity with the aforementioned female monster-figures to which we have already attributed derivation from the proto-Indo-European mara. However, in the case of the Seaside- nightmare we are referring to here, the etymology is controversial: there are those who attribute it to a proto-Indo-European sea (crushing, oppression), some in Greek Μόρος (destiny).

[12] Claudia Giontella, Marica and the Palici: a comparison between “terrible” entities cultured in a beneficial sense, in “Usus Venerationem Fontium, Proceedings of the International Study Conference on“ Fruition and Cult of Healthy Waters in Italy ”, edited by Lidio Gasperini, Rome-Viterbo 29-31 October 1993, Tipigraf Editrice, 2006, pag. 235

[13] Remo Bracchi, op. cit., pp. 91-92

[14] Valentine Osterman, Life in Friuli. Customs, customs, popular beliefs, Institute of Academic Editions, Vidossi, Udine, 1940, p. 213

[15] Alberto Borghini, Mandraule, the salamander, in: «Varia Historia. Narration, territory, landscape: folklore as mythology », Aracne Editrice, Rome, 2005, pp. 217-228

[16] For further information on the rain-mandrake link, see my article Storm Solanaceae, quoted in the first note of this work

[17] Pliny, Naturalis Historia, X, 188

[18] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, op. cit., pp. 132-133

[19] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, op. cit., p. 127

[20] Ibidem

[21] Pliny states that the salamander "it is so cold that on contact the fire is extinguished not differently from the effect produced by the ice"(Pliny, Naturalis Historia, book X, chap. LXXXVI)

[22] In fact, the salamander's skin glands secrete a substance that irritates the mucous membranes. For Pliny even the salamander drool had the power to cause whitish spots on the body of anyone who came into contact with it (power also attributed to the gecko in the popular tradition of the South).

[23] Paracelsus, Free from nymphis, sylphis, pygmaeis and salamandris (1566)

[24] Alberto Borghini, op. cit. (2005), p. 120

[25] Alberto Borghini, op. cit., 2005, p. 220

[26] Ibidem

[27] Ibidem

[28] Ibidem

[29] Ibid, p. 223

[30] Gianfranco Mele, Laùri and mandrake, in: "The mandrake in Puglia and in the land of Otranto", Terra d'Otranto Foundation, website, January 2018 http://www.fondazioneterradotranto.it/2018/01/05/la-mandragora-puglia-terra-dotranto/

[31] Salvatore Lentini, Carlo Cominelli, Angelo Giorgi, Pier Paolo Merlin Petroglyphs of historical age in Valcamonica (Central Italian Alps): comparison of iconographic documents and oral memory, in: «Post-medieval archeology, society, environment, production» n. 10, In the sign of the lily, 2006, p. 183

[32] Salvatore Lentini et al., Op. cit., p. 189

[33] Ibidem

[34] Ibid, pp. 189-90

[35] Matthew Cantacuzeno, Canticum Canticorum salomonis, Byzantine Commentary sec. XIV

[36] Jerome Coppola The Marial or Mary always Virgin Mother of the Incarnate verb, and Lady of the Universe, Crowned with privileges. Predictable speeches by Fr Girolamo Coppola, Regular Cleric, Venice, 1754, pp. 174-75; Marc'Antonio Sanseverino, Lent of the PD Marc'Antonio Sanseverino, Naples, 1664, p. 12

[37] Vittorio Rugarli, The "city of Umbria" and the Mandrake, in: "Magazine of Italian popular traditions", edited by Angelo De Gubernatis, Year I, Issue I, Forni Editore, Bologna, 1893

[38] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, op. cit., p. 138

[39] Ibidem

[40] Ibidem

[41] Ibid, p. 138

[42] Numerous testimonies around the Mandrake are linked to its discovery during the harvest of hay, which, moreover, are associated with the perturbations following the uprooting

[43] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, op. cit., p. 139

[44] Antonella Lattanzi, The kingdom of the elves, in Legends and folk tales of Puglia, Newton Compton Editori, 2006, pp. 64-74

[45] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, op. cit., p. 139

[46] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, op. cit., p. 140

[47] Ibidem

[48] Ibid, p. 141

[49] Ibid, p. 142

[50] Pliny, Naturalis Historia, Book VIII, par. 78-79

[51] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, op. cit., Toro, p. 143

[52] Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, op. cit., Toro, p. 144-47

[53] Gianfranco Mele, At the origins of Laùru, the nightmare sprite, in La Voce di Maruggio, November 2018, https://www.lavocedimaruggio.it/wp/alle-origini-del-lauru-lo-spiritello-incubo.html

[54] There are many insights into the power of the basilisk's gaze: for a quick summary, see http://www.paesidivaltellina.it/basilisco/index.htm . For further and more detailed notes and descriptions regarding the "powers" of the basilisk and its representations in legend and in time, see Valentina Borniotto, "Rex serpentium": the basilisk in art between natural history, myth and faith, in “Studies in the History of the Arts”, n. 11, years 2004-2010, De Ferrari Ed., Pp. 23-47

[55] The work, attributed to the Painter of Dione, is currently kept in Milan. Here the complete card http://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/reperti-archeologici/schede/G0370-00839/?view=categorie&offset=15&hid=500&sort=sort_int

[56] Oreste Caroppo, The Salento chameleon, in "Naturalization of Italy", website, February 2013, http://naturalizzazioneditalia.altervista.org/il-camaleonte-salentino/

[57] Even in recent times specimens have been observed and photographed in the Salento countryside: at the time of writing I was able to see one in a post spread on a social network, found by chance, picked up and photographed in the countryside of Nardò.

[58] Oreste Caroppo, What is the "Squinzano monster" that emerges from a profound past? In "Naturalization of Italy", website, February 2021, http://naturalizzazioneditalia.altervista.org/cosa-e-il-mostro-di-squinzano/

[59] Ibidem

[60] Retrieval specifications, from the find sheet: "Perhaps from Squinzano (Lecce); purchased from the Convent of the Oblate Benedictine Sisters of Ostuni (Brindisi); recovery prior to the notification of 11 November 1934; hypothetical association in one or more Messapian funerary objects."

[61] This is the description included in the description of the find with reference to the present figure: "Side A: Crowned satyr, naked, with himation on his shoulders, thyrsus in the left and flute in the right, chasing a draped maenad; this flees to the left, turning her head in the direction of the satyr; in the left he holds a thyrsus. On the right side of the scene a parallelepiped stele is painted. At the center between the two characters is a small bipedal monstrous being, with a reptilian body, long tail, deformed face and feral ears; the monster is without comparison in the iconographic documentation. "

[62] Alberto Borghini, Elf and basilisk sphere: elf-reptile; elf-bird. Some ideas, in Essays from the Italian Museum of Folklore Imaginary, 2006, https://saggi.museoimmaginario.net/index.php/saggi/folletto-e-sfera-del-basilisco-di-a-borghini/

[63] “Cista cibaria”, that is an artisanal basket usually used to transport hay, food and light weights in general

[64] Alberto Borghini, Elf and basilisk sphere: elf-reptile; elf-bird. Some ideas, on. cit.

[65] Ibidem

[66] Ibidem

[67] Ibidem

[68] A young man eager to discover the realm of "fade", famous for their bewitching beauty, meets on their way first an ogre, then a beautiful "fada" (which will turn into a repulsive old woman), then two basilisks, then a little man (elf) keeper of a treasure.

[69] Aurelio Garobbio, Legends of the Lepontine Alps and Grisons, Rocca San Casciano, Cappelli, 1969, p. 51

[70] Remo Bracchi, And the stars are watchingand, in Bulletin of the Historical Society of Valtellinese, n ° 54, 2001

[71] Alberto Borghini, Elf and basilisk sphere: elf-reptile; elf-bird. Some ideas, on. cit.

[72] Ibidem

[73] Ibidem

[74] Ibidem

[75] http://www.paesidivaltellina.it/basilisco/index.htm

[76] Ibidem

[77] Ibidem

REFERENCES:

Matthew Cantacuzeno, Canticum Canticorum salomonis, Byzantine Commentary sec. XIV

Oreste Caroppo, The Salento chameleon, in "Naturalization of Italy", website, February 2013

Oreste Caroppo, What is the "Squinzano monster" that emerges from a profound past? In “Naturalization of Italy”, website, February 2021

Jerome Coppola The Marial or Mary always Virgin Mother of the Incarnate verb, and Lady of the Universe, Crowned with privileges. Predictable speeches by Fr Girolamo Coppola, Regular Cleric, Venice, 1754

Dante Bertini, Singing and cantàri. Poems in Venetian dialect with a glossary added, Notebooks of Poetry Ed., 1931

Alberto Borghini, Mandraule, the salamander, in: «Varia Historia. Narration, territory, landscape: folklore as mythology », Aracne Editrice, Rome, 2005

Alberto Borghini, Elf and basilisk sphere: elf-reptile; elf-bird. Some ideas, in Essays of the Italian Museum of Folklore Imaginary, 2006

Alberto Borghini, Gianluca Toro, Mandrake, salamander and reptiles: elements of correspondence, in “Lares”, vol. 76, n ° 2, May-August 2010

Valentina Borniotto, "Rex serpentium": the basilisk in art between natural history, myth and faith, in “Studies in the History of the Arts”, n. 11, years 2004-2010, De Ferrari Ed

Remo Bracchi, Names and faces of fear in the Adda and Mera valleys, DeGruyter, 2009

Remo Bracchi, And the stars are watching, in Bulletin of the Historical Society of Valtellinese, n ° 54, 2001

Aurelio Garobbio, Legends of the Lepontine Alps and Grisons, Rocca San Casciano, Cappelli, 1969

Claudia Giontella, Marica and the Palici: a comparison between “terrible” entities cultured in a beneficial sense, in "Usus Venerationem Fontium, Proceedings of the International Study Conference on" Use and Cult of Healthy Waters in Italy ", edited by Lidio Gasperini, Rome-Viterbo 29-31 October 1993, Tipigraf Editrice, 2006

Antonella Lattanzi, Legends and folk tales of Puglia, Newton Compton Publishers, 2006

Salvatore Lentini, Carlo Cominelli, Angelo Giorgi, Pier Paolo Merlin Petroglyphs of historical age in Valcamonica (Central Italian Alps): comparison of iconographic documents and oral memory, in: «Post-medieval archeology, society, environment, production» n. 10, Under the banner of the lily, 2006

Gianfranco Mele, Laùri and mandrake, in: "The mandrake in Puglia and in the land of Otranto", Terra d'Otranto Foundation, website, January 2018

Gianfranco Mele, At the origins of Laùru, the nightmare sprite, in La Voce di Maruggio (website), November 2018

Gianfranco Mele, Storm Solanaceae, in "Elsewhere" n.21, Nautilus Edizioni, 2020

Valentine Osterman, Life in Friuli. Customs, customs, popular beliefs, Institute of Academic Editions, Vidossi, Udine, 1940

Paracelsus, Free from nymphis, sylphis, pygmaeis and salamandris, 1566

Pliny, Naturalis Historia, Book X

Vittorio Rugarli, The "city of Umbria" and the Mandrake, in: "Magazine of Italian popular traditions", edited by Angelo De Gubernatis, Year I, Issue I, Forni Editore, Bologna, 1893

Marc'Antonio Sanseverino, Lent of the PD Marc'Antonio Sanseverino, Naples, 1664