In ancient Egypt it was essential to propitiate the forces manifested by the divine incarnations, through religious rituals and those relating to the magical sphere, mainly by correctly exploiting rites and functions, in order to transform the danger of the animal into a powerful protection: precisely for this reason, in fact, the crocodile was invoked in an attempt to safeguard the Egyptian people, in particular from the dangers of the Nile.

di Carlotta Dioguardi

The experience of the divine in the Egyptian world

Since the most ancient period of history the Egyptian religion it stands out from the rest of the Mediterranean world for its composite plurality and its changing character, which makes interpretations and definitive theories equally complex.

As often highlighted by research carried out by modern scholars, a peculiarity of the Egyptian world is a high feeling of individual participation in the sphere of the sacred, which is not isolated in an unattainable ontological category but which on the contrary is an indissoluble part of daily life, taking root in social context and stratifying in history. The Egyptian religion consequently presents itself as a context in constant evolution, in which image and essence alternate, in a complete cyclical dynamism which transforms appearances into substances, reality into appearances, describing an entirely celestial experience within a terrestrial sequence.

Without ignoring historical coordinates and anthropological references, it proves necessary to enter with caution into an attempt to illustrate what the divine was supposed to represent in an absolutely real way, with what criteria was chosen to give shape to the latter and through which symbols, finally arriving at his representations.

One of the fundamental themes that characterizes the Egyptian religion of the ancient world lies in the importance of the word and the role it plays in the context of the creation and manifestation of the divine: in this case the word takes on the function of a real vehicle through which the individual undertakes a profound communication with the otherworldly world and manages to entertain a relationship with divinity. It can be said that in the Egyptian worldview the word is the best means to objectify the divine in terms of a concrete realization, making the very essence of the celestial sphere preachable.

The bond that underlies the principle of identity between name and substance it is of a strictly related nature and is nourished by the correspondence that exists between the two sets; furthermore, knowledge is part of this interdependence, making itself specific to both environments: just as the essence is shown through the word, so the word is made up of the substance itself, alternating a continuous exchange of authority and power.

Consistent with what has just been written, the term "divinity" or "god" is described with a blurred outline. The words of the divine they range in variety and interpretation and it is almost impossible to give a univocal and certain translation: starting from the most neutral definition, indicating "that which is venerated", the meanings alternate a static character, the divine principle itself, and a creative character, as the manifestation of power or the emanation of the extraordinary supernatural.

Trying to maintain a line of research that allows for a fair amount of clarity, we can consider the Egyptian terminology of the divine as a means intimately shared by the community of individuals to represent reality and describe their own human experience, as the possibility of undertaking a growing dialogue with the invisible and as a transposition of the superhuman into the system of the word, within the boundaries of the temporal and the aspectual.

If one of the oldest ways to call god was Sekhem, which seems to refer to a meaning specific to the sphere of authority and power elevated beyond the physical level, manifested in spiritual space through its owner, the more generic terms are equally fundamental, such as the word netjer, concepts relating to belonging to the divine, such asAh and Ba or even deified abstract concepts.

While the word Netjer, refers to the hieroglyph of the fetish in the predynastic era and gradually changes its representation into an anthropomorphic form only after the first half of the Old Kingdom, being traditionally identified as the basic form of determinate for the divinity, other elements perhaps prove to be of greater complexity of the divine who find themselves in a position of subtle demarcation between natural and supernatural. In this last meaning, in fact, we can inscribe theAh and Ba, two concepts whose relationship with the human acquires value and constitutes one of the most important pieces of Egyptian cosmology ancient, as well as potentially defining its entire spiritual orientation. The direct and explicit link that is expressed between the divine world and the individual is reflected in the words Ah, literally attributable to energy and light, and Ba, translated by moderns as "capacity" or "manifestation", as well as in their derivatives, thus opening a horizon that includes all levels of the cosmos [1]. In this way each individual and divine entity is animated by these forces and disposes of them in a multiple way, drawing from similar sources which are nothing other than different nuances of the same principle.

In Egyptian religion one can therefore assume this semantic alternation as a symbolic motif of one cyclical regeneration, in whose arrangement the above-mentioned elements must be understood as non-exclusive energies, which flow in the depths of the universe through earthly creations, involving every phase of human existence, from birth to death.

Some of these particular distinctive features of the Egyptian vision of the earthly and otherworldly world, which we have only mentioned here, are able to offer an idea, albeit indefinite, rather explicit of what the divine represented for the community: it is therefore not only of the god but of his own and contemporary representation, together with the mixture of abstract and concrete, real and imaginary characters. We must ignore a linear interpretation of the mythical events and religious conceptual developments since in the Egyptian vision, everything is a phase of a cycle and as in a sort of endless metonymic path, every single part summarizes the entire cyclicality in itself. Finally, as in much of the history of ancient religions, it is necessary to renounce the claim of a complete understanding and a finite interpretation, since much of what we are about to deal with or that we have mentioned so far is the result, exceptional and worthy of centuries of historical research, yet distant in time and space from the Egyptian culture of those centuries.

In the context of a religious system that lives the experience of being not as a reproduction of reality, but as a search for elements in communion with sacredness, new meanings can be read which cover in double alternation the positive and the negative, the divine world and the earthly world, the human and the animal.

Divinity in the Egyptian world:

between zoolatry and anthropomorphism

As we mentioned in the previous paragraph, Egyptian religion has always maintained a component of as a constant of specificity dynamism and multiformity. In this sense, we proceed with a brief description of the representations of the divinity and the physical and symbolic characteristics that characterized it from the most ancient period to that of Roman domination.

In Ancient Egypt the first representations of the divinity are not exactly similar to those imagined by moderns: religious iconography is made up in its first phases of that phenomenon called zoolatry and of which it will be necessary to spend some considerations. In the Egyptian world the cult of sacred animals it was practiced since the Protodynastic period (ca. 3000-2686 BC) and progressively intensified in a decidedly more punctual and determined way until it also reached the New Kingdom (ca. 1550-1069 BC) and its subsequent even more elaborate formulations [2].

The religious practice of zoolatry is therefore to be found in antiquity, more precisely from the XNUMXth millennium BC, a period in which the burials of animals considered sacred, especially wild ones, multiplied considerably and which presents itself as a historical phase of extreme cultural development for Near Eastern societies. It is necessary to specify the extent of the usual burial activity, which occurred for any animal that had some type of interaction with the sacred environment, but was distinguished into two apparently similar forms but with very different meanings: if in fact animal burials were found in honor of the deity, with the function of sacrificial offering, and therefore definable as votive necropolises, were however very different burials of sacred animals, or individual specimens chosen from the vastness of the species present in the area.

As regards the iconography, starting from the instruments for cosmetic use often bearing the shape of a fish, perhaps with the function of an amulet, continuing with the sacred objects decorated with animal figures in relief, we finally reach the votive palettes, which make clear the importance of the animal element in the environment of the divine and its representation. In fact, on the latter several episodes are visible, usually fights and battles with typically human tones, whose protagonists are involved in symbolic transformations and become an emblem of supernatural dispositions and qualities. Only the losers of these clashes maintain the human form, highlighted by the nudity assigned to them by the illustrations, the winners instead take on the appearance of strong and vigorous animals, such as lions and bulls, in the image of that symmetrical analogy typical of the relationship between power and otherworldly world.

This type of figures coming from Egyptian art allow us to imagine more clearly what the real relationship was that the Egyptians lived with the natural and physical environment that surrounded them, whereby elements from the vegetal and animal environment of the territory become a vehicle of social and collective communication as well as a unique opportunity to contact the divine. A manifestation in reality of concepts belonging to the sphere of the cosmos, which are inextricably intertwined with everyday life, thus expressing themselves also at a level of everyday life and which highlights the absence of boundaries between animal and human. In the expressions of Egyptian religion, this conception will be what will allow the consistent presence of deities with fluid features, who manifest themselves with a human head and an animal body and vice versa, or who still present typical characteristics of several animals at the same time, making it difficult to identify them in the physical realm.

Le hybrid figures, which with a good deal of amazement and declared difficulty were first reported to us by the Greek and Roman historians of the ancient period, are tangible proof of the fact that, at least initially, the animal world was certainly considered stronger than man according to common Egyptian thought. Consequently, according to this interpretation, the animal was necessarily linked to the divine world in a more solid way and also retained within itself a power that man would hardly have been able to match.

In the context of historiography, a finding of impressive beauty, the interpretation of which allows us to carry out an analysis of the evolution of Egyptian thought in relation to divinity, the relationship with power and with the animal world, is represented by Narmer votive tablet, probably dating back to the end of the Predynastic period and whose depictions show a change in perspective.

On the famous paddle it is possible to observe some animals typical of Egyptian symbolism linked to power, protection and strength, such as the heads of cow with human features in the highest part, the bull in the lower part intent on breaking down the walls of a city and trampling on an opponent and finally the falcon which, holding a noose in its claws, tightens the neck of an enemy. The interpretation that identifies the bull and the hawk is now considered certain symbolism of the pharaoh, in Ancient Egypt considered as a divinity and in some way an undisputed and privileged intermediary between the otherworldly world and the human world.

However, what makes the study of the Narmer tablet even more interesting is the presence of a depiction of the pharaoh also in anthropomorphic form and from whose kilt hangs a bull's tail, the last trace of an outdated zoolatry and of a heterogeneous and new vision of divine, in which anthropomorphism and zoomorphism complement each other. The elements and forms typical of the animal context thus become traditionally recognized tools for affirming the authority of the pharaonic role, as well as its belonging to the divine world.

It should not be surprising that all the characteristics just described can be found in Egyptian religious iconography, where it is possible to find divinities with hybrid features present at the same time, or sometimes represented in human form, other times in animal form. Likewise the statue, which in the Egyptian world is nothing other than a real Ba of the god, or rather his real manifestation, presents the same traits and the ritual was carried out, as supported by various scholars, by wearing animal masks by the priests who impersonated the god of mythology.

The role of animals was absolutely primary in Ancient Egypt, occupying an inviolable space worthy of unconditional consideration: it can be said that man's relationship with the animal kingdom was one of the most frequent occasions for investigating the boundaries of the sacred , within the limits of a complex and articulated relationship.

In the case of some animals, the attestation of the cult together with the burials are found starting from the most ancient dynasties, but it is essential to remember that in Ancient Egypt the veneration of animals was something more than a simple visual similarity or a mere sacrifice to the celestial divinity: the animal form was a real intermediary between human and divine and represented divinity on earth. The god incarnated himself in an animal that was not his property but the incarnation of his active strength and his grandeur: for this reason, the animals venerated in Egypt never included the entire species, but were only a few selected specimens that presented specific characteristics, in accordance with the image of the deity and the evident manifestation of his power.

Through this continuous and cyclical exchange of communication and representation, starting from veneration and reaching sacred iconography, the zoological and otherworldly garden served as an intermediary and deployed through its officials, first of all the pharaoh followed by the priests who specialized in the sacred, the interminable powers, regenerated forces, overwhelming fertility and all that, as previously mentioned, swung like a pendulum between the sphere of man and the sphere of god.

The crocodile in Ancient Egypt:

divine animal or god incarnate?

Il crocodile it is one of the most frequent animals whose cult is already found in the ancient period of Egyptian religious iconography. Described as a fearsome reptile and a dangerous predator, often considered a symbol of strength and fertility, in the Egyptian divine imagination the crocodile inspires feelings of profound magic and is intertwined with mythology, covering monstrous roles with undisputed power: its movement between the aquatic and terrestrial environments with dexterity places it in a changing and dual dimension interpretation, representing a potentially lethal creature but at the same time connected to the world of fertility and abundance.

In ancient Egypt it was fundamental propitiate the forces manifested by the divine incarnations, through religious rituals and those relating to the magical sphere, mainly by correctly exploiting rites and functions, in order to transform the dangerousness of the animal into a powerful protection: precisely for this reason, in fact, the crocodile was invoked in an attempt to safeguard the Egyptian people, in particular from the dangers of the Nile.

An excellent example of the symbolic function assumed by the crocodile, even in its simple animal form, is visible in the famous Cippus of Horus on crocodiles, a small basalt stele used for magical-medical purposes, probably dating back to the period of domination of the last Egyptian dynasty (Late Period ca. 664-332 BC), covered with formulas and inscriptions on all its sides.

Due to the functioning of the stele and the manifestation of the divinity, the presence of words together with the images was fundamental: the water that flowed over it absorbed the power of the inscriptions and it is probable that whoever drank it could perceive the strength of the god in their body. The scene concerning Horo on the crocodiles is found in the central point of the stele: it is about Horus, falcon god connected to pharaonic power, depicted completely naked with the body of a child, standing on a crocodile, holding two scorpions and two snakes, the tail of a lion and the horns of an antelope in his hands. The invincible strength of the divinity is here made concrete by the iconography, through the choice of dangerous and strong creatures, such as scorpions, lions, antelopes and of course, crocodiles: the latter, unlike the other animals, are however not found in a constrictive, but somehow at the service of the divinity, demonstrating that the relationship with these animals had to be built and potentially exploited as a protection tool.

The Crocodile God: Sobek's Power

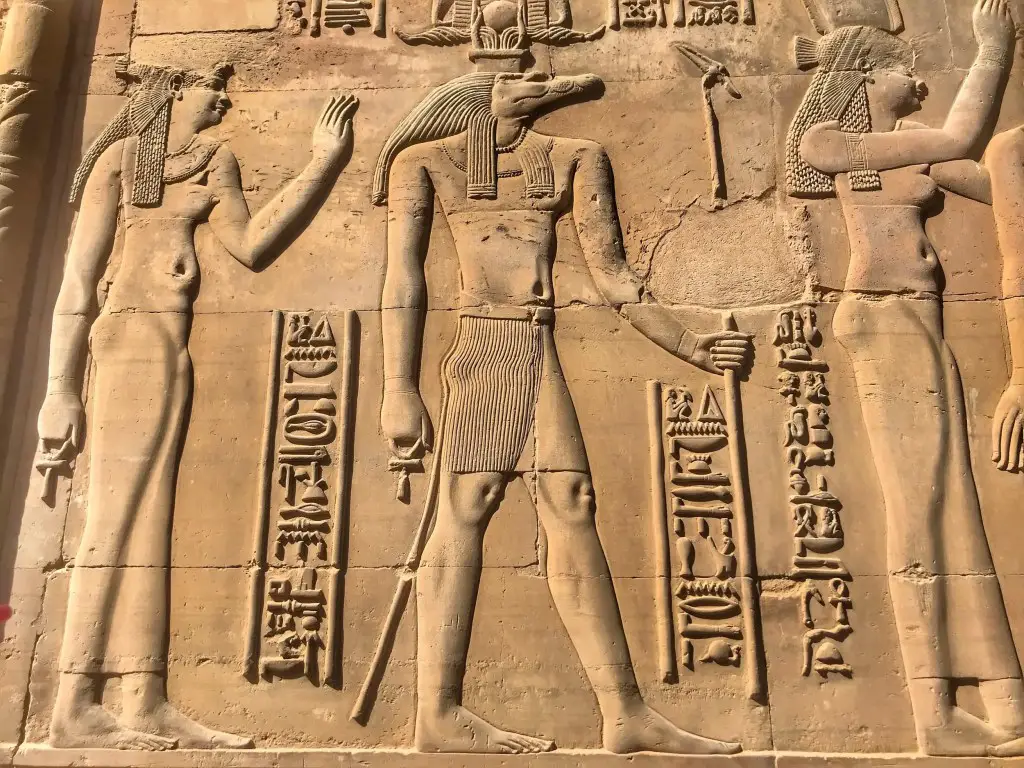

Going beyond animal symbolism, a real crocodile god is worshiped in Ancient Egypt with the name of Sobek: in sacred texts the god is described with tones of magnificence and splendor, and his role is ambiguous and at times provocative. One of the most famous texts reported by the sources and chronicles of the Roman period is the so-called “Book of the Fayum”, an ancient writing in which mythical and celebratory events of the god Sobek are narrated, partly reported on the walls of the temple of Kom Ombo.

In related inscriptions, the god Sobek is often associated with the solar deity, commonly referred to by the name of Ra, and also takes on the role of powerful original god connected to creation; some of these representations seem to understand Sobek as a true manifestation of the god Ra, who makes his journey along the Nile aboard the solar boat to dive into the Duat (or Lake Moeris) at the end of the daily journey of death and rebirth. Furthermore, as mentioned above, lSobek's assimilation to the primordial god and his connection to the aquatic environment, in addition to the high prolificacy of the crocodile, it also transfers its influence to sphere of sexuality and reproduction:

He created the Nun in his time, a great god from whose eyes came the two stars (the sun and the moon, eyes of the sky), his right eye shining during the day, and his left eye during the night [ …] The Nile flows like its living sweat and fertilizes the fields. He acts with his phallus to flood the Two Lands with what he has created. […] How sweet it is to pray to him, he who listens and comes to those who call him, perfect in sight, rich in ears, who is present at the words of those who need him, strong, victorious, to whom no one resembles. He is the most prestigious of the gods in his strength, Sobek-Ra lord of Kom Ombo, who loves clemency after wrath.

[3]

Its body is described as large and powerful, covered in green feathers and metallic shades and whose eyes are always alert [4]. Although Sobek keeps his animal form almost completely unchanged, the god manifests a powerful divinity, often described alternating a disruptive sexual charge with an attitude of power that borders on violence: in the same way through which he can take possession of the throne and begin the solar and pharaonic cycle of birth, death and rebirth, he can mate with the women he desires, without worrying about their partners.

Especially in relation to Sobek's connection with the sexual sphere, the relationship between the female universe and the crocodile will be interpreted in the Egyptian imagination as problematic and potentially dangerous, in fact as reported in some papyri, women who dreamed of sexually uniting with a crocodile were close to death. The god Sobek represents one of the most changeable and versatile divinities of the Egyptian world as his role, which has always been linked to water, is transformed in his representations into a god participating in the celestial sphere and personification of the solar god, as well as a possible incarnation or vicar of Osiris, taking on his funerary function.

The iconographic representations of Sobek are therefore of different types: often depicted in the form of a simple crocodile or mummified crocodile, he also had a hybrid form, composed of a human body and a crocodile head. According to some texts, Sobek's mother was Neith [5], creator and warrior deity, associated with the primordial waters of the Nun, often defined neutrally by the epithets of “Mother of mothers”, “Father of fathers”: one of the oldest deities of Egyptian religion, the iconography of the less archaic periods depicts Neith in anthropomorphic form and bearer of the red crown of Lower Egypt.

The territory most involved in the cult of the crocodile was certainly the area corresponding to the Fayyum, an originally marshy area, subsequently reclaimed and transformed into a cultivated plain, and in whose capital Shedet, or Krokodilopolis (literally “City of the Crocodile”, according to the Greek authors who describe it), its largest sanctuary was built. The Fayyum area, and in particular its capital, are located in the central area of the region and consequently the cult of the crocodile represents a fundamental element that takes on a role that is not only geographically strategic but also ideological and religious.

The historian of the XNUMXst century BC Diodorus Siculus tells us how the cult of Sobek dates back to the period in which the sovereign reigned menes, perhaps a legendary version of the pharaoh Narmer, who, chased by a pack of dogs, was saved by a crocodile that made him climb onto its back: once he landed on the shore, the sovereign had a sanctuary and the city built, and ordered his inhabitants to venerate the crocodile. Naturally, there were many other sacred places in Sobek in all the cities located throughout the Egyptian territory, such as those identified in the cities of Euhemeria, Karanis and Kom Ombo, within which there must have been an incarnation of the god.

The description of what happened inside the temples dedicated to the crocodile deity can be an excellent opportunity to understand the practical dimension that the Egyptian cult took on in its daily forms and how fundamentally unitary the spiritual and material experience was:

Crocodiles are sacred to some Egyptians [...] Those who live around the city of Thebes and Lake Meris consider them absolutely sacred: in both these regions they provide for the maintenance of a crocodile chosen from all the others, trained and domesticated: they decorate its ears with pendants of enamel and gold, and with rings on the front legs, they feed him with chosen foods and victims of sacrifices, in short, treating him in the best way while he is alive. When he dies they embalm him and bury him in sacred niches.

[6]

In the sanctuaries of Sobek there were actual tanks dedicated to the breeding of sacred crocodiles which, according to the chronicles of Greek and Roman authors, were fed with delicacies of all kinds, unimaginable offerings and adorned with jewels and very precious stones. As per the quote from the Greek historian Herodotus, the sacred crocodiles were obviously also mummified and buried in special designated areas, of which we have various archaeological findings in some sites in Egypt, such as Tell Maharaqa, Tuna el Gebel and Kom Ombo.

A unique case that deserves particular attention is that linked to the site of Medinet Madi, in which during the Middle Kingdom period (ca. 2025-1773 BC) a temple dedicated to the goddess Renenut associated with the serpent, and flanked by another temple dedicated to the cult of Sobek in the Ptolemaic era (ca. 332-30 BC). In this place, during the excavations which took place in the last decades of the 1900s and conducted by a team of archaeologists led by the University of Pisa, the presence of a double shrine was identified, it is hypothesized intended for the veneration of two sacred specimens of crocodile, perhaps a pair. Finally, this site is also linked to the discovery of tanks most likely dedicated to the breeding of small crocodiles and within which some still intact crocodile eggs were found. [7].

Beyond Sobek: the image of the crocodile functional to the deities

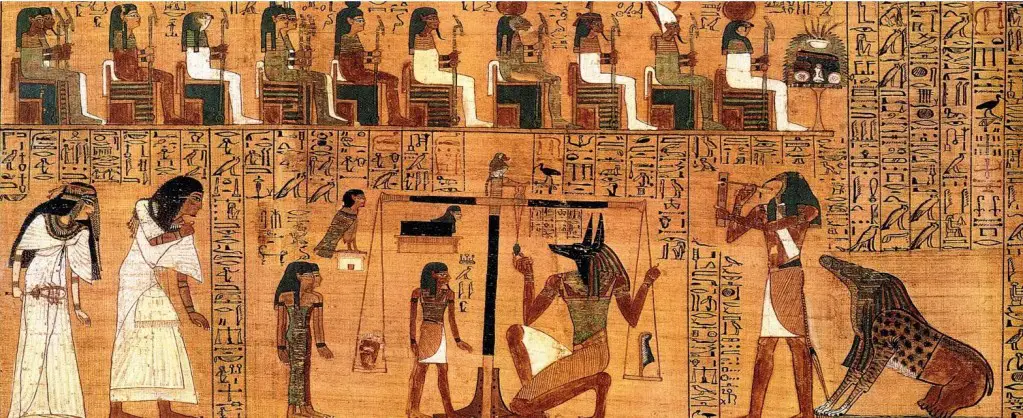

Although Sobek remains the main crocodile god with the clearest iconography, it is out of a desire for exhaustiveness and completeness that we mention other deities who take on physical characteristics typical of this animal in the Egyptian imagination. One of the most famous is certainly Ammet, mythological figure halfway between goddess and monster, also known by the epithets "Devourer of the dead" and "Eater of hearts" and, according to some, divine representative of the lake of fire found in the afterlife: in chapter 125 of Book of the Dead she is represented waiting to devour the heart of the deceased after the ritual of weighing the heart. Ammet is usually depicted as a hybrid deity, with her front body part like that of a lion, her rear body part like that of a hippopotamus, and the head of a crocodile.

Its role is emblematic and as already described previously, strongly characterized by animal symbolism linked to strength and destructive power of ferocious and extremely dangerous creatures: lion, hippopotamus and crocodile are all animals that in ancient Egypt undoubtedly represented one of the greatest and most fearsome dangers in the area.

The ferocious goddess Ammet was the protagonist of the moment of judgment at the end of life: also called “Chapter of the Heart”, was often reported on amulets in the shape of a scarab, a solar and pharaonic symbol, placed near the heart of the deceased at the time of burial, as auspiciousness and protection on the journey to the afterlife. Once he reached his second declaration of innocence, during the trip in the Duat, the afterworld, the deceased was subjected to judgment by a host of deities, including Thot, god of wisdom and guarantor of justice, who ensured the correct conduct of the trial, and the goddess Size, personification of cosmic order and balance, whose head feather placed on the scales had to be lighter than the heart of the deceased.

If judged innocent, once the ritual was finished, the deceased could continue his journey in the funerary afterlife to reach the body of Osiris, to which he would have joined thus completing the solar daily cycle and participating in Ra's journey on the solar boat. If the deceased's heart had been too heavy, as a result of bad actions committed by the condemned man while alive, he would have been swallowed up by the monstrous goddess Ammet and his soul would have been destined to a condition of eternal restlessness and oblivion. It can be said that the goddess Ammet is the embodiment of punishment, inflicted indiscriminately on the individual who has not acted in accordance with the principles of Maat, winged female divinity and personification of abstract concepts which, as mentioned, concerned harmony, justice, balance , as well as the rejection of excess and disorder.

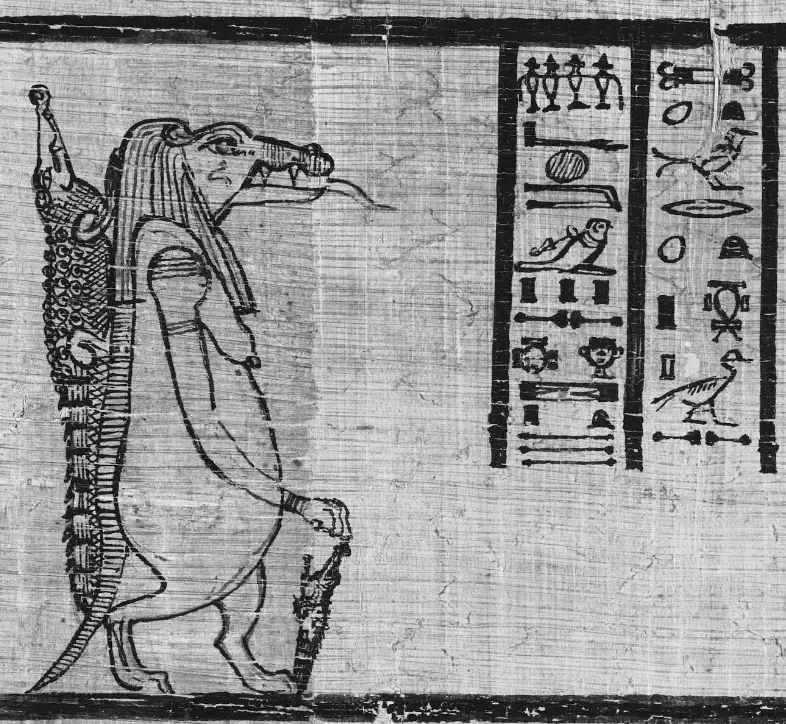

Another female deity with a hybrid body is the goddess Tawereth, whose cult we have evidence of since the Old Kingdom and whose role has often been reinterpreted. Depicted with a hippopotamus body, crocodile crest, lion paws and human arms, the goddess Taweret is a mild goddess, associated with the sphere of fertility and motherhood: her large breasts are evident and her round belly, demonstrating her role as protector of women giving birth as well as mothers, his name is also found in numerous magical-medical formulas to ensure the health of the newborn.

The goddess Taweret was often invoked during childbirth so that the latter could take place easily, avoiding complications and difficulties, also symbolically uniting the moment of birth with the divine environment: as a maternal divinity, Taweret was always present at the rise of the solar god Ra East, a moment considered as a true rebirth from the primordial ocean of Nun. Her symbol was the amulet named Sa, whose meaning was that of “protection”, and which was graphically represented as a set of papyrus canes held at the ends by a lace. We are not yet certain what the actual use of this instrument was, but it was certainly associated with the function of an effective instrument against evil and dangers: often the goddess Taweret, as in the statue above, rests her paws on the amulet as an image strengthening her power.

Some figures similar in appearance to Taweret and often unified under the same iconography or name are the hippopotamus goddess Ipet, known by other names such as Ipy, also associated with the feminine sphere and represented while breastfeeding the pharaoh from her breast and the aforementioned Neith, mother of Sobek, connected to creation and consequently to motherhood.

Some stars and other divinities have links with the image of the crocodile, always in relation to the sphere of power and strength: the constellation that we know today by the name of Great Bear, mentioned several times in Egyptian sacred texts, was considered imperishable and perpetual, in fact their Egyptian name literally means "those that do not fade”. The stars of the Big Dipper were represented in a deified form with the entire spinal column composed of a crocodile, probably a hybrid between the god Sobek and Ra, and ensured the rebirth of the pharaoh through the journey made between earth and sky.

Although rarely, the violent and bloodthirsty god khonsu, protector of the pharaoh, is sometimes represented with a human body and crocodile head. The god Khonsu was worshiped mainly in the city of Thebes and was described as a lunar god, of ancient veneration and who nevertheless underwent numerous transformations in the course of Egyptian religious history: this divinity, in fact, transformed from man-eating god, guarantor of the pharaoh's strength, a god of time, with the head of a falcon and a human body, and again in the Middle Kingdom he becomes a child god linked to the Theban triad with Amon and Mut.

Shed, a god connected to the Nile environment and to the activity of a hunter, venerated starting from the New Kingdom as a child, is represented standing on crocodiles; he is assimilated to Horus above all by virtue of the depictions of him holding wild and dangerous animals such as antelopes or snakes in his hands. The god Shed often also carries a bow and arrows with him, demonstrating his role as lord of the hunt and master of the wild animal kingdom.

NOTE:

[1] R. Buongarzone, The Egyptian gods, Carocci Editore, 2007.

[2] For information on the history of Ancient Egypt, see N. Grimal, History of Ancient Egypt, Laterza, 1998.

[3] E. Bresciani, Religious texts from Ancient Egypt, Mondadori, 2001, p. 238.

[4] For complete formulas, see Pyramid Texts, formula 317.

[5] E. Bresciani, Sobek, Lord of the Land of the Lake. In Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt, editor. Salima Ikram, Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005, pp. 199-206.

[6] Herodotus, Stories, book II, Bur Rizzoli, p. 241.

[7] E. Bresciani, Sobek, Lord of the Land of the Lake. In Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt, 2005.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

C. Riggs, Ancient Egyptian magic, Thames & Hudson, 2020.

DB Redford, The Ancient gods speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion, Oxford University Press, 2002.

E. Bresciani, Large illustrated encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Ed. De Agostini, 1998.

E. Bresciani, Sobek, Lord of the Land of the Lake. In Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt, editor. Salima Ikram, Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2005.

E. Bresciani, Religious texts of ancient Egypt, Mondadori, 2001.

Herodotus, Stories, Bur Rizzoli.

G. Filoramo, What is religion Themes, methods, problems, Einaudi, 2004.

G. Filoramo, M. Massenzio, M. Raveri, P. Scarpi, History of Religions Manual, Laterza Publishers, 1998.

J. Assmann, Death as a Cultural Theme – Mortuary Images and Rites in Ancient Egypt, 2000.

JP Allen, The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta, 2005.

M. Verner, The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments, Grove Press, 2002.

M. Zecchi, Religious Geography of the Fayum, La Mandragora Publishing House, 2001.

M. Zecchi, Sobek of Shedet: The Crocodile God in the Fayyum in the Dynastic Period, Umbria: Tau Editrice, 2010.

N. Grimal, History of Ancient Egypt, Laterza, 1998.

R. Buongarzone, The Egyptian gods, Carocci Editore, 2007.

S. Quirke, Exploring Religion in Ancient Egypt, Wiley Blackwell, 2014.

The word Sekhem which identifies the Egyptian god refers to the authoritarian power of the Sachem among the American Indian populations. Very interesting topics to explore in a thoughtful reading

I take the opportunity of this article to share a small suggestion that has been nagging me for some time: I therefore invite you to make an independent reflection on the architrave at the entrance to the Collegiate Church of San Quirico D'Orcia

As usual, the “esoteric” or “occult” websites while interesting for a while, leave me with the feeling of time wasted with myths generated by dualistic mind imaginings entirely within the mirage known as maya, the mundane samsara.

If “civilization” is ever to escape the dark age in this time cycle, instigated by the self-chosen tribe, one must venture beyond the wall, out of the sleep-walking West to the Ancient superior knowledge (vidya is knowledge, not of things or ideas but direct knowledge).. of the East. Thereby slowly re-gaining the former powers of man, held before the Fall (the instigation of Abrahamic Religions – Religare: to hold back, block from progress.