In view of Shirley Jackson's birth anniversary we are publishing this literary retrospective of the main works of the Californian writer, from The Nightmare of Hill House a The lottery, from the meridian a The Witch, concluding with We have always lived in the castle.

di Paul Mathlouthi

It happens more and more often in our area too that the writers who are protagonists of the happy season of weird tales o penny dreadfuls whatever you want to say, that is, the periodical publications which, between the end of the XNUMXth century and the first half of the XNUMXth century, made the fortune of Horror literature in the Anglo-Saxon world, are rediscovered by courageous publishers who are not inclined to the fashions dictated by pre-packaged cultural industry and experience an unexpected second youth.

Se Abraham Merritt (1884-1943), explorer of underground civilizations cleared by the Palermo publishing house Il Palindromo which, thanks to the meritorious work of Andrea Scarabelli, re-proposed in 2018 Ishtar's ship, returns today to show off itself in the Mondadori catalog with two indispensable titles such as Burn witch, burn! e Strip, shadow!, the merit of having recently rescued from oblivion and translated a little jewel of the Gothic genre as The house and the brain di Edward Bulwer Lytton (1803-1873), brought to new life by the Milanese Aspis in a precious edition edited by a high-ranking Lovecraftian like Pietro Guarriello.

A similar fate in many ways, despite the difference in tones and pitches, is that which occurred in the native letters to Shirley jackson (1916-1965). Desperate housewife who in the practice of writing short, explosive and anguished dark stories has found an outlet for chronic depression corroborated by the abuse of alcohol and psychotropic drugs, a necessary substitute for the stormy and tormented love for Stanley Edgar Hyman, university professor and a flamboyant critic who was both tormentor and mentor to his talented wife, for a long time he occupied a marginal, not to say rhapsodic, position in the editorial panorama of our home, although he enjoyed a certain notoriety in his homeland, achieved through assiduous collaboration on the cultural pages of the “New Yorker”.

Marking the change of pace in the reception of his work by Italian readers was, once again, the late Roberto Calasso who, with the proverbial, infallible foresight for which he is famous, republished it in the Adelphi catalog in 2004 The Nightmare of Hill House, inaugurating the rediscovery of a writer otherwise unknown to the general public. It must be said, to be honest (and I hope the many fans of her today will not be mad at her), that the title chosen to inaugurate this successful revival is certainly not among the most representative of Jackson. A perfectly thought-out narrative mechanism from a formal point of view, the novel, which also boasts a couple of famous film adaptations and served as the leitmotif for a renowned television series, proposes the theme again, which has risen to the rank of a real mantra Edgar Allan Poe forward, of cursed abode endowed with a sinister conscience in which the unfortunate guests remain trapped in spite of themselves as in a tomb. The situations described sin, in my humble opinion, of excessive mannerism and the protagonist, the anthropologist John Montague, resembles other famous Occult investigators, his predecessors, such as Martin Hesselius and John Silence, too closely for the reading to be truly enjoyable. convincing to the core and arouse, in those who venture into these pages, a sense of authentic, disturbing apprehension [1].

If pure Horror, that is, understood in a supernatural and metaphysical sense, is not exactly in her style, on the other hand Shirley Jackson is very good at revealing, I would say from direct experience gained in the field, those who Henry David Thoreau he would call the abysses of quiet desperation that hide behind the screen of an apparently anonymous and irreproachable lifestyle, as happens, for example, in the story The lottery. In this case, the backdrop to the narrative is an unspecified location lost in the unfathomable vastness of the immense American province. The protagonist is a community of hardworking and God-fearing farmers who once a year, at the end of June, gather in a public square to draw lots for the name of one of their fellow villagers who is literally stoned to death for apotropaic purposes, because the inhabitants they believe his death could promote the success of the harvest.

It resurfaces, transfigured in the form of an apologue, the archetypal scapegoat which in all likelihood Jackson, who grew up in a rigidly confessional educational context, borrowed from the biblical episode of Isaac, who willingly lent himself to be sacrificed to the Lord at the hands of his father Abraham (Genesis, 22). Second René Girard, who dedicated two essays of capital importance to the topic, especially in pre-modern societies - and the one described by Jackson is undoubtedly so in the underground dynamics that animate it - the ritual killing of an innocent victim like Tessie Hutchinson serves, on a symbolic level , to deflect the violence that governs social relationships by channeling it onto a defenseless target whose death, not claimed because it is considered in some way indispensable for the maintenance of the established order, is aimed at strengthening cohesion between the members of the community and equally has a significant salvific, since the shed blood cleanses the human assembly of its sins. Girard specifies:

Men in groups are subject to sudden changes in their relationships, for better or for worse. If they attribute a complete cycle of variations to the collective victim that facilitates the return to normality, they will necessarily deduce from this double transference the belief in a transcendent power, one and twofold at the same time, which alternately brings them damnation and salvation, punishment and the reward. This power manifests itself through violence of which it is the victim, but even more so the mysterious instigator.

[2]

A dialectic that, over the centuries, has governed all forms of persecution in history: the myth of Salem is eternally renewed. In fact, violence is ultimately the underlying theme of Jackson's writings. A primordial impulse that smolders under the ashes, harnessed by the constraints and prohibitions of social life, which occasionally resurfaces on the surface, breaks the circle of conventions and deploys all its explosive destructive force, especially where our attention threshold is lowest in when we rationally believe we are safest, that is, within the family context. Flannery O'Connor once said that if you survive childhood, you have writing material for a lifetime. Lesson that Jackson has made her own with subtle mastery of psychological investigation, revealing a domestic microcosm based on the principle of the most sinister oppression which heralds, in substance if not in form, the dark atmospheres evoked, for example, by Truman Capote in In cold blood which, perhaps not surprisingly, was published by its multifaceted author a year after the writer's death.

In Jackson's prose, children are eyewitnesses to an adult world with marked Freudian connotations which, far from being protective and nurturing, looms over them in monstrous forms. If in the novel the meridian it is the very young Fancy Halloran who announces to her astonished relatives, with the disarming candor typical of her tender age, that it was none other than her grandmother who killed her father by throwing him down the stairs, willing to sacrifice the life of the only son and heir of the house so as not to have to share it with her much-hated daughter-in-law, the little protagonist of the story The Witch he is approached on the train by an unknown traveler who, in a completely unexpected and surprising way for the reader, fuels his fervent imagination with a terrifying anecdote:

“Tell me about your sister – said the child – was she a witch?” “Maybe,” the man replied. The boy laughed enthusiastically and the man leaned back and took a drag on his cigar. “A long time ago,” he began, “I had a little sister, just like yours.” The child looked up at him, nodding at every word. “My little sister,” the man continued, “she was so cute and nice that I loved her more than anything in the world. So do you want to know what I did?”. The child nodded more eagerly, and her mother looked up from the book and smiled, listening. “I bought her a rocking horse, a doll and a million lollipops,” the man said. “Then I took hold of her, put my hands around her neck and held her, held her until she died.”

[3]

In one of his famous essays, Bruno Bettelheim has acutely observed that the dominant thought has also eliminated the theme of conflict from literature intended for children, in favor of a horizontal and inclusive narrative, based on a generic philosophy of self-realization, which in no way corresponds to the authentic psychic universe of the child and therefore of the man in progress [4].

Shirley Jackson, on the contrary, driven by the awareness that Evil like Virtue is omnipresent and that only from the osmotic ambivalence between opposite polarities can the resolution of the internal conflicts that tear us apart, has recovered the archaic and therefore authentically formative function of the fairy tale which is traditionally interwoven with shadows. In his writings the Darkness not only exists and therefore one must be adequately prepared to face it, but it releases a magnetic power of seduction which is embodied in despotic, affectless and unequivocally demonic female figures.

Mary Katherine Blackwood and her sister Constance, protagonists of the novel We have always lived in the castle, appear, at a first superficial investigation, like a couple of sour and slightly eccentric spinsters, because the Author never gives up the perverse taste of peppering an otherwise distressing narrative with a few notes of color with a farcical flavour, but by delving into the plot the bucolic context in which the story is inserted progressively gives way to darkness and we discover that our heroines are actually two witches, who spend their time disseminating the perimeter of the estate in which they have chosen to segregate themselves with amulets useful to keep away intruders and the spirits of the deceased. What's more, they share the unhealthy passion for cultivating harmful plants and fungi from which very powerful poisons are distilled, like the one used to exterminate all the members of their family and thus be able to preserve their morbidly incestuous bond from undue interference. The story ends with the inhabitants of the village who, armed with torches and pitchforks, lay siege to the Blackwood sisters' mansion to deliver it to the flames from which the two unfortunates miraculously emerge unharmed, in a scene which, for dramatic emphasis , cannot help but bring to mind i great inquisitorial stakes of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries.

Subverting with baroque wit the canonical narrative structure of our fairy-tale heritage, in an irreverent interweaving of situations suspended between the dazed and the scabrous in which a powerful note of macabre humor, Shirley Jackson embraces Grimilde's point of view and, in outlining the physiognomy of her black ladies, brings an archetype back to the center of the narrative, that of woman who engages in commerce with the supernatural, in which that unsolvable dualism that we know is the foundation of the cosmic order reverberates.

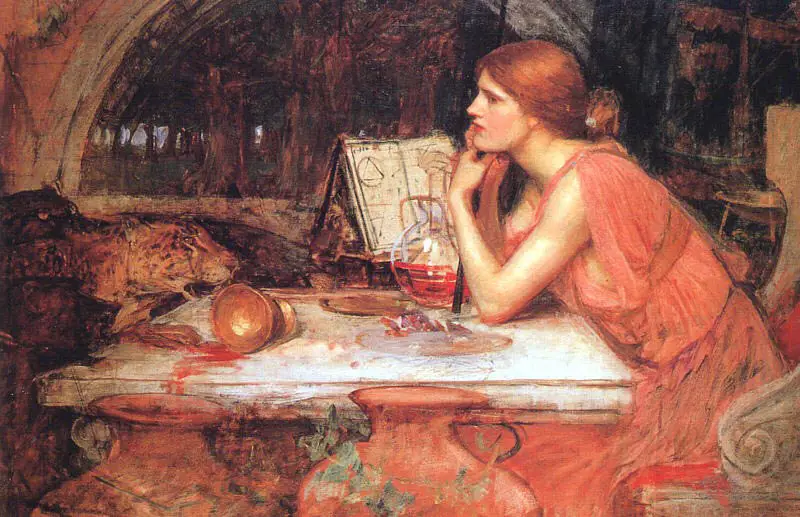

Furthermore, Classicism has handed down to us the memory of the two enchantresses par excellence, Circe and Medea, who, despite being sisters, just like Constance and Mary Katherine, nevertheless embody two antithetical models of femininity. If Circe, whose potions give an oblivion that dampens the pressure of time, is capable of being moved and feeling compassion, to the point of restoring freedom to Ulysses and his companions at the right moment, Medea, on the contrary, orders, subdues , strikes and literally feeds on the blind desire for revenge that fuels her fury as a betrayed lover. Both daughters of Hecate, the triple lunar Goddess who supervises the kingdom of the dead, however it is Medea, according to Ovidio, to invoke the protection of the mother to assist her in her bloody purposes:

O Night, faithful friend of the mysteries and you, who with the Moon succeed the lights of day, golden stars, and you, three-headed Hecate, who respond to my appeal to receive the confidence of my plans and to give them help with which you favor the singing and art of magicians, offer me your support.

[5]

He echoes it Seneca, which condescendingly, almost complicitly, lends itself to giving free rein to the sinister thoughts of its champion, portrays her while talking to herself and appeals to the silent shadows, to the funereal Gods, to the gloomy living room of the dark Pluto and to the souls torn from the edges of Tartarus:

O faithful accomplices of my works, now turn your anger and your divine will against the houses of your enemies [...]; give me an evil more atrocious than death to wish on my husband.

[6]

A dull hatred that turns into iconoclastic violence along the way and leads Medea to sacrifice the lives of her own children in order to deprive Jason of a legitimate lineage, just as happens to the doyenne of the Halloran house.

Again according to Ovid, Medea is also the barbaric poisoner, who reaps terrible plants with her enchanted scythe. In fact, she knows how to use all the herbs of the earth which, if necessary, she mixes with the venom of reptiles, finally adding a drop of her own blood: all iconographic elements which will pass, almost unchanged, into medieval symbolism, to constitute the stereotypical image of the witch as it has come to us, with the only non-negligible exception that, since the voice of the ancient Gods is now indecipherable to our ears, its actions are placed under the auspices of Lucifer. Having escaped the persecutions unscathed, Medea now takes her deserved revenge and is reborn "in new forms above the changed world", as she would have said Novalis, finding shelter in Jackson's pages, hidden just behind the veil of literary fiction.

NOTES

[1] Published in the first edition in 1959, The Nightmare of Hill House It has seen two film adaptations. The first appeared in American theaters in 1963 with the title The possessed, directed by Robert Wise. The second version created by Jan de Bont with the title dates back to 1999 Haunting – Attendance, which stars Liam Neeson as Doctor Montague (aka David Marrow). In 2018, the Netflix production company created a ten-episode television series entitled The Haunting of Hill House, created and directed by Mike Flanagan.

[2] René Girard, The scapegoat, Adelphi, Milan 1987; p. 77. On the same topic, reading the essay is also recommended Violence and the sacred, signed by the same author, also appeared at Adelphi in 1980.

[3] Shirley Jackson, The Witch, Adelphi, Milan 2023; pp. 14-15pm.

[4] Bruno Bettelheim, The enchanted world. Use, importance and psychoanalytic meanings of fairy tales, Feltrinelli, Milan 1984.

[5] Ovid, Metamorphosis, VII, vv. 191-198.

[6] Seneca, Medea, vv. 740-751.