Tag: Krampus

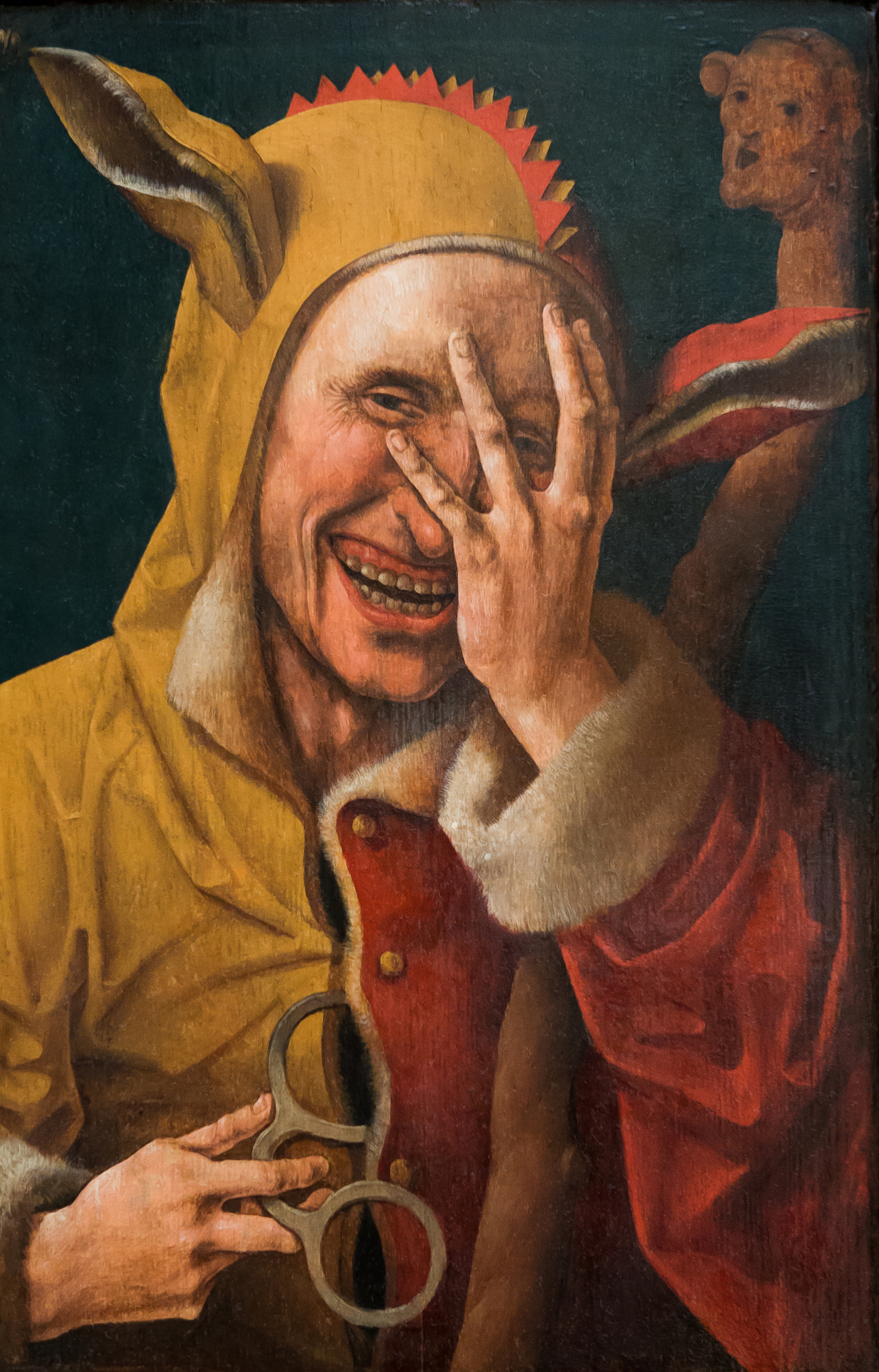

Fools, shamans, goblins: liminality, otherness and ritual inversion

The peripheral location of the Folle / Buffone / Jester of the medieval era links him, as well as to the archaic Shaman, to other liminal characters of myth and folklore, such as the Wild Man, Harlequin, the Genius Cuckold and more generally to all that category of feral entities connected on the one hand to the demons of vegetation and on the other to the functional sphere of dreams and death. With regard to the rite, the Folle is to be seen connected to the so-called "ritual inversion" that was carried out during the Roman Saturnalia and during all those collective walking rituals of the Charivari type from which the "Feste dei Folli" were born in the Middle Ages. and the modern Carnival.

"Santa Claus executed", or the eternal return of an immortal rite

With an essay with a provocative title, "Santa Claus executed", Claude Lévi-Strauss is inspired by a bizarre news event at his time - the hanging and holocaust of a puppet of Santa Claus by the Dijonese clergy - to arrive to the understanding of the "true meaning of Christmas", based on the reciprocal relationship between the world of children and that of the dead. The method used for this purpose is a synchronic and confrontational approach with non-European societies.

Cernunno, Odin, Dionysus and other deities of the 'Winter Sun'

di Marco Maculotti

cover: Hermann Hendrich, "Wotan", 1913

[follows from: Cosmic cycles and time regeneration: immolation rites of the 'King of the Old Year'].

In the previous publication we had the opportunity to analyze the ritual complex, recognizable everywhere among the ancient Indo-European populations, centered on theimmolation (real or symbolic) of the "King of the Old Year" (eg. Roman Saturnalia), as a symbolic representation of the "Dying Year" that must be sacrificed to ensure that the Cosmos (= the order of things), reinvigorated by this ceremonial action, grants the regeneration of Time and of the 'World' (in the Pythagorean meaning of Kosmos like interconnected unit) in the new year to come; year which, in this sense, becomes a micro-representation of the Aeon and, therefore, of the entire cyclical nature of the Cosmos. Let's now proceed toanalysis of some divinities intimately connected with the "solstitial crisis", to the point of rising to mythical representatives of the "Winter Sun" and, in full, of the "King of the Waning Year": Cernunno, the 'horned god' par excellence, as far as the Celtic area is concerned; Odin and the 'wild hunt' for the Scandinavian one and Dionysus for the Mediterranean area.

The Friulian benandanti and the ancient European fertility cults

di Marco Maculotti

cover: Luis Ricardo Falero, “Witches going to their Sabbath", 1878).

Carlo Ginzburg (born 1939), a renowned scholar of religious folklore and medieval popular beliefs, published in 1966 as his first work The Benandanti, a research on the Friulian peasant society of the sixteenth century. The author, thanks to a remarkable work on a conspicuous documentary material relating to the trials of the courts of the Inquisition, reconstructed the complex system of beliefs widespread up to a relatively recent era in the peasant world of northern Italy and other countries, of Germanic area, Central Europe.

According to Ginzburg, the beliefs concerning the company of the benandanti and their ritual battles against witches and sorcerers on the Thursday nights of the four tempora (Her hand, imbol, Beltain, Lughnasad), were to be interpreted as a natural evolution, which took place far from the city centers and from the influence of the various Christian Churches, of an ancient agrarian cult with shamanic characteristics, widespread throughout Europe since the Archaic age, before the spread of the Jewish religion - Christian. Ginzburg's analysis of the interpretation proposed at the time by the inquisitors is also of considerable interest, who, often displaced by what they heard during interrogation by the benandanti defendants, mostly limited themselves to equating the complex experience of the latter with the nefarious practices of witchcraft. Although with the passing of the centuries the tales of the benandanti became more and more similar to those concerning the witchcraft sabbath, the author noted that this concordance was not absolute:

"If, in fact, the witches and sorcerers who meet on Thursday night to give themselves to" jumps "," fun "," weddings "and banquets, immediately evoke the image of the sabb - that sabb that the demonologists had meticulously described and codified, and the inquisitors persecuted at least since the mid-400th century - nonetheless exist, among the gatherings described by benandanti and the traditional, vulgate image of the diabolical sabbath, evident differences. In these cEverywhere, apparently, homage is not paid to the devil (in whose presence, indeed, there is no mention of it), faith is not abjured, the cross is not trampled, there is no reproach of the sacraments. At the center of them is a dark ritual: witches and sorcerers armed with sorghum reeds who juggle and fight with benandanti provided with fennel branches. Who are these benandanti? On the one hand, they claim to oppose witches and sorcerers, to hinder their evil designs, to heal the victims of their hexes; on the other hand, not unlike their presumed adversaries, they claim to go to mysterious nocturnal gatherings, of which they cannot speak under pain of being beaten, riding hares, cats and other animals. "

—Carlo Ginzburg, "I benandanti. Witchcraft and agrarian cults between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries», Pp. 7-8