First part of our translation of the comparative study, hitherto unpublished in Italian, on the ancient religions of Jerusalem and Mecca. Edited by Andrea Casella.

di Hildegard Lewy

«Archiv Orientalàlnì», Prague, vol. 18, folder 3 (Nov. 1, 1950) pp. 330-365.

Translation by Andrea Casella.

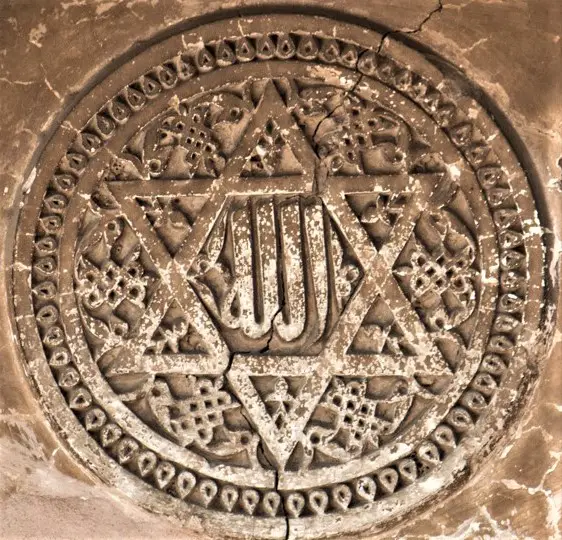

Just as countless mosques in the Near East are surmounted by the Crescent Moon, the most modern synagogues are identified by the six-pointed star, which is usually called Mâgên Dâwîd, “the shield of David”. The original meaning of this symbol, which has been the subject of a great deal of speculation [1], is somewhat clarified by its presence on two Old Assyrian seal impressions found on cuneiform tablets AO.8758 [2] and AO.8781, etc. [3] owned by the Louvre Museum. On the seal impression of the first tablet, the Mâgên Dâwîd appears in front of a character of divine rank who holds in his hands a ceremonial object very similar to a menorah. The co-presence on an ancient Assyrian seal of these two emblems which are generally considered so characteristic of the Jewish faith, clarifies that none of them has its origin in the religion of Yahweh, since, as known, there is no evidence that this religion was ever practiced in Assyria in the ancient Assyrian period.

The sigil image found on tablet AO.8781, etc., provides some important information about the Mâgên Dâwîd. The reason is that therein it is closely associated with two emblems whose meaning is well known, namely the crescent moon and the solar disc. The connection of our six-pointed star with these two symbols of planetary deities, the Moon-god Sîn and the Sun-god Ŝamaŝ, suggests at first glance that it was itself the representation of a planetary god, a conclusion that is the most plausible of all, since five-, six-, seven- and eight-pointed stars were used elsewhere in the ancient Near East to represent the planetary gods. As examples we mention the eight-pointed star that the stone tablet BM 91000 [4] he ascribes, on the relief of his obverse, to the goddess Iŝtar, the divine representative of the planet Venus, and another eight-pointed star which he represents, according to an explanatory legend on the reverse of tablet AO.6448 [5] the god Nabû-Mercury. Since the emblems of four of the seven planetary gods [6] are well identified from cuneiform sources, the Mâgên Dâwîd it can represent only one of the three planets whose symbols remain to be identified, namely the so-called superior planets, Jupiter, Mars and Saturn.

Šalim's relationship with the Davidic Dynasty

Since tradition attributes the six-pointed star to both David and Solomon [7], the decision to assign it to one of the three planets it would symbolize largely depends on the question, if so, of which of these three superior planets played a part in the religion of these two kings. An indirect indication that Yahweh was not the only divine being worshiped by David and Solomon is contained in the statement taken from First Book of Kings, III, 2 that the practice of offering sacrifices in high places (a practice which according to I Kings, III, 4 was followed by Solomon) was not in accord with the religion of Yahweh. It is easy to speculate that the non-Yahwistic cult alluded to here was a planetary religion, since, as we have pointed out elsewhere in great detail [8], the worshipers of the stars believed that the tops of hills or mountains - that is, in the absence of natural relief - the upper clearing of the towers of the temples, were the appropriate place to meet the astral deities, being such places closer to their celestial abode compared to the uninhabited plain. The inference that Solomon worshiped on Gibeon and other high places was a planetary deity is perfectly in line with the episode, immediately following the aforementioned passage from the Book of Kings, according to which his famous wisdom was infused into him in a dream on the summit of Mount Gibeon. Therefore, as we have demonstrated in our aforementioned work, the conception of a king who, in a dream revelation, is gifted with wisdom and knowledge far superior to those of an ordinary man, can be found elsewhere only in relation to rulers who were declared worshipers of the stars [9].

An indication of the planet's identity that appears to have played an important role in Solomon's religion comes from the name of his older brother, 'Amnôn. Since, as evidenced by J. Lewy, this name is derived from the root '-mn- with the addition of the suffix -ô/ân, we are authorized to render it with “He Who Belongs to the Stationary” [10]. Since Saturn was the planet that the peoples of the ancient Near East designated as "The Stationary" (Akkadian Kaimanu, Sumerian SAG.Uš [11]) we come to the conclusion that this was the star deity to whom David had consecrated his firstborn.

We can also hypothesize why he did it: in the belief of the ancient Semites, a ruler who proposed to conquer a certain city or a certain country had to obtain the favor of the tutelary divinity in order to be chosen to reign there by grace of his divine patron [12]. This conception was a logical consequence of the ideas of divine power widespread in the Near East. Since the patron deity of a famous city (or country) is supposed to be far more powerful than the most powerful king on earth, it was unthinkable that a human being would be in a position to conquer a city or region against the will of his patron god. [13]. It is therefore reasonable to think that David, planning to conquer Jerusalem, should have paid homage to the tutelary deity of that city. Now some information about the god who is thought to have owned the city of Jerusalem before Yahweh can be deduced from the name itself: ירושלם (Neo-Assyrian âlUr-sa-li-im-mu [14]). As J. Lewy first pointed out [15], this name, being composed of an element ירו (to be linked to ירה, “to create”, “to found”) and the divine name Shalim (recurring also in the variants Š/Salim and Šâlôm), means “Creation of Šalim”, a meaning which makes it clear that the god called Šalim was considered the divine creator and protector of Jerusalem. In fact, from a passage – likewise clarified by J. Lewy [16] -, of the letter of Amarna VAT 1646 it follows that âlBît dŠulmâni, “city of the temple of the god Šulmânu”, was one of the names under which the capital city of mâtÚ-ru-sa-lim-ki, “the country of Jerusalem”, was known in the period of the Tell-el-Amarna Letters, i.e. at the beginning of the XNUMXth century BC As the Assyrian name Šulmânu is derived from Šalim or Šâlôm with the addition of the aforementioned suffix ân/ôn in addition to the final Assyrian callsign -u [17] the designation of the city as âlBît dŠulmâni confirms our earlier conclusions that the god Šalim or Šulmânu was the chief deity of pre-Israelite Jerusalem. As to the nature of this divine patron of the famous city, J. Lewy [18] concluded from the Assyrian vocabulary K. 4339 that the Assyrians identified him with their god Ninurta. That this identification, far from being a mere artifice of the learned author of that vocabulary, expressed the general belief of the Assyrians is demonstrated by the fact that an Assyrian king who, choosing as his name Šulmânu-ašarid ("Šulmânu is the Supreme [i.e. among the gods]”), put himself under the special protection of the patron god of Jerusalem, founded the city of Kalḫu, the Assyrian residence of the god Ninurta [19]. Since the latter divinity was the divine personification of the planet Saturn [20], it then becomes clear that the Šulmânu of the Semitic West also personified the planet that Assyrian astronomers and astrologers used to call "The Night Sun". In the light of this evidence, it is difficult to remain any doubt that calling his eldest son 'Amnôn, "He who belongs to Saturn" [21] David had paid honor to the tutelary god of Jerusalem. Because, second II Samuel, III, 2, 'Amnôn was born in Hebron long before David embarked on his campaign to conquer Jerusalem, it is obvious that he had consecrated his firstborn to the planet Saturn so that this god could choose him and his descendants to reign over the holy city. This conclusion is justified by the fact that 'Amnôn was not the only one of David's sons whose name expressed paternal reverence for the planet Saturn. Once it is realized that in his capacity as creator and protector of Jerusalem this deity was called Šalim or Šâlôm, it is clear that David's third son, Ab-Šâlôm, whose name means "The Father is Šalim", also bore a name which placed him under the protection of the divine lord of Jerusalem. The same is obviously true of Solomon whose name means "He who belongs to Šalim". We thus realize that David was perfectly aware of the condition linked to the conquest and possession of Jerusalem: from now on an important place in the pantheon of the royal family would be occupied by Šalim, the divine patron of the capital.

By observing, in the manner described above, the ritual practices customary among the worshipers of the stars, Solomon, son of David and his successor, gave evidence of having accepted the patronage of this planetary deity. The question therefore arises as to the extent to which he attempted to impose the cult of Šalim on his subjects. This question is best resolved by determining whether Solomon's Temple as conceived by David and Solomon was in principle dedicated to Yahweh or to Šalim; since, in the opinion of the ancient Semites, a sanctuary built in honor of a certain god was a powerful means of propaganda of his cult [22].

The main sources of information on the cult of the planet Saturn

Before trying to determine whether the Temple of Solomon and the traditions around it reveal in any way a relationship with the cult of the planet Saturn, we must briefly discuss the main sources from which information about the god and the forms of his cult can derive . Let us say first of all that Saturn was the patron deity of the city of Lagaš, south of Babylon, where he was revered under the name of Ningirsu, "Lord of Girsu" (Girsu being the name of an area of Lagaš [23]). Thus the inscriptions dealing with the later reconstructions of Ningirsu temple, theIt's-ninnû, and in particular the detailed accounts left by Gudea, may represent a number of useful data for our investigation. From these texts we learn above all that Ningirsu was worshiped together with his "beloved consort" [24], the goddess Bau, who (being considered the daughter of Anu, the sky god) is frequently referred to as "the queen, the daughter of the pure sky" [25]. We also learn that Ningirsu was conceived as a mighty warrior equipped with terrible weapons, and that he was frequently styled as "He who stops the raging waters". [26].

The myth where this last epithet is originally found is preserved in a text that the ancients designated as Lugal-e ud me-làm-bi nir-gàl, “King, Storm, whose splendor is heroic” [27]. The poem, which was probably recited or performed during the annual festival celebrated in the city of Nippur, south of Babylon [28], in memory of its supposed foundation by the god Ninurta, narrates that there was a time when a terrible flood threatened all living beings with death and destruction [29]. Ninurta then resolved to hasten to the aid of his creatures, and came in boat to meet the enemy [30]. The deluge was not the only opponent he met on the battlefield, since the stones had sided with the rising waters, and this on the basis of the idea that during a flood many large and small stones fell on the cities and villages with great damage and destruction [31]. Some stones, however, changed sides in the course of the battle and aided Ninurta against the flood. This part of the myth can perhaps be explained by assuming that some rocks had piled up to form a dam against the rising waters. Be that as it may, the battle ended in the complete victory of Ninurta, who "damped in the enemy country" [32] the hostile waters of the flood. Thus we understand that by invoking the planet Saturn as "He who stops the furious waters", the people of Lagaš attributed the end of the destructive deluge to their god.

The parts of the poem which relate the events after the Flood (tablets IV to VII) are very fragmentary; the only clear part is contained in tablet V, where it is said (rev., l. 6, Geller, loc. cit., p. 287) that Ninurta "built a wall", probably using the stones that had been dragged away from the flood. On tablet VIII, on the other hand, we still have a complete account [33]. Here it is said that, probably as a result of Ninurta having confined the flood waters to the "enemy country," there was a shortage of fresh water throughout the region, with the result that agricultural activities came to a halt. But again Ninurta came to the aid of his people. In the mountains he gathered huge stones with which he built a city (ll. 15-19 of Langdon's text). Then he collected the waters that had flooded the fields and discharged them into the Tigris River [34]. Then the Tigris swelled and filled with water the network of canals on which the success of every agricultural operation depended. After this work was done, Ninurta appointed his mother, the earth goddess, ruler of the city he had built. [35], for she had valiantly helped him in his fight against the Flood (tablet IX).

Finally, some of the myths and traditions contained in this ancient Sumerian epic of Ninurta recur in the remaining fragments of the History of Phenicia of Sanconiatone [36]. This comparatively late source names a deity Ἠλος or Κρόνος as one of the most important gods worshiped by the Phoenicians [37]. That he was an astral deity follows from our text's statement that Kronos-Elos was revered as the "star of Kronos." Since in the terminology of the Greeks the "star of Kronos" [38] is the planet Saturn, there are few doubts that for the Phoenicians Sanconiatone took care of this planet was El, the god par excellence.

The Phoenician god Saturn, just like his Babylonian counterpart, was believed to be the son of the earth, reported by Philo of Byblos as Gê [39]. He too was involved in a terrible war [40], after which victorious outcome he "surrounded his house with a wall and founded as the first city of all Byblos of Phenicia" [41]. Thus we learn that in Byblos, as in Nippur, the worshipers of Saturn believed that their city had been founded by their god as the first city in the world and that this settlement was built around a sanctuary of Saturn surrounded by a wall. In further agreement with the Babylonian myth the Greek version relates [42] that the newly founded city was given by Saturn to his mother, whose name, Baaltis, undoubtedly has the meaning of "Lady (of Byblos)." On the other hand, Sanchoniathon's account contains information about the god Saturn of which there is no trace in any Babylonian source: if, as a result of wars, pestilence or other general calamity, the faithful of Saturn were threatened with catastrophe, it was customary for the head of the respective community to sacrifice his most beloved son to that planet [43]. This custom, in turn, is explained by the myth that Saturn himself sacrificed his son on the altar when plague threatened his followers. [44]. child sacrifice seems to have been such a typical feature of the cult of the planet Saturn that even in the Middle Ages this star was known as “the planet that devours its children” [45].

Finally, our study of the cult of the planet Saturn must make use of medieval Arab sources, not only because they contain mythical reminiscences of pre-Islamic Arab religion, but also because they describe the cult of planetary deities practiced in the Near East up to the time when the Turks , more intolerant than their predecessors, they did not extinguish the last remnants of the ancient Semitic religions. Ad-Dimišqî, who devotes an entire chapter of his Cosmography to the religious practices of the worshipers of the stars, reports that a temple of Saturn "was built in the shape of a hexagon, black (according to the colour) of the worked stone and the curtains" [46]. While, judging from the ancient temple of Saturn in Lagaš, as elsewhere, the reference to the hexagonal shape must be the result of a confusion [47], the predominance of the color black is well in line with the information provided by the cuneiform sources; since there, no less than in medieval works of astrology, Saturn is frequently called the "black" or "dark" planet [48]. However, an observation by al-Mas'ûdî [49] suggests that the entire temple did not necessarily have to be built of black stone; for when this author reports that, in the opinion of the worshipers of the stars, the Ka'aba of Mecca passed for being a sanctuary of Saturn, he points out that this characterization depended on the presence of a sacred black stone, the famous Ḥağar al-aswad. The correctness of al-Mas'ûdî's information is proved, at least indirectly, by the name of the god who, according to the unanimous testimony of our Islamic sources, was worshiped in the Ka'ba in the period before Muhammad. He was called Hubal (هبل) [50], a name which, derived from the root هبل [lever ed], has the meaning of "He who violently deprives the mother of her child" [51]. The way the divine lord of Mecca was believed to take children from their mothers is illustrated by the well-known legend about Muhammad's grandfather, 'Abd al-Muṭṭalib. It is said that he sacrificed one of his sons to Hubal, in case he was blessed with ten sons. [52]. Thus it is clear that the god worshiped in the Ka'aba used to accept, or perhaps demand, child sacrifices by his worshippers. Since, as we have seen above [53]such sacrifices were considered a highly characteristic trait of the planet Saturn, there remains no doubt that the tradition that the Ka'aba was a shrine to Saturn is more reliable than is generally thought [54]. In fact, when the Koran (III, 96) establishes that the temple located in Bakka (ie the Ka'ba of Mecca) was the first sanctuary built for men, it alludes to a tradition which, as seen above, is characteristic of the places of the cult of Saturn: in each of these cities, the worshipers believed that their sanctuary and their city were the first to be founded [55].

NOTE:

[1] Regarding some of these speculations about the possible meaning of the Mâgên Dâwîd you see Jahrbuch für Judische Volkskunde I, Berlin-Vienna 1923, pp. 391 et seq. and p. 392, note 1.

[2] A reproduction of the seal impression in question is found in J. Lewy, Cappadocian tablets, third series, third lot (Louvre Museum, Department of Oriental Antiquities, Cuneiform Texts, vol. XXI), Paris 1937, pl. CCXXXV, no. 74.

[3] For a reproduction of the seal impression on this last fragment see J. Lewy, op. cit., pl. CCXXXIII, no. 48. - Professor Herbert G. May has kindly called my attention to the fact that the Mâgên Dâwîd it is engraved on the wall of a shrine in Megiddo; see his work Material remains of the cult of Megiddo, Chicago 1935, p. 6 and fig. 1 on p. 7. According to archaeologists, the wall in question dates back to the XNUMXth-XNUMXth century BC

[4] See LW King, Babylonian boundary stones e Memorial tablets in the British Museum, London 1912 pl. XCVIII, and cf. Thureau-Dangin, Journal of Assyriology XVI, 1919, p. 139.

[5] See Thureau-Dangin, loc. cit., p. 135 and cf. Orientalia 18, 1949, p. 168, note 1.

[6] That is Sîn, Ŝamaŝ, Iŝtar and Nabû.

[7] While Jewish tradition refers to our symbol as "David's shield", Islamic sources rather designate it as "Solomon's seal".

[8] See Archiv Orientalàlni XVII (Symbolae Hrozný, vol. II), Prague 1949, pp. 87 ff.

[9] See loc. cit., p. 87, where, with reference to tablet BM 38299 (the so-called Verse report), Nabû-na'id is reported to have been chosen as the recipient of divine wisdom by the Moon-god. With regard to letter K. 2701a it further appears that Sîn-ahhê-erîba was believed to have received the same gift from the Assyrian national god, Aššûr. That, in the conception of the Neo-Assyrians, Aššûr was an astral deity results from passages such as BM 81, 7 – 1,4 (for this text see below, note 111) l. 1, where the divine patron of Assyria is identified with kakkabApin, “the plow-star”. On this constellation, which roughly overlaps what is now called the Triangle, see Schaumberger, Starnkunde und Sterndienst in Babel, 3. Ergänzungsheft, Münster 1935, pp. 328 ff.

[10] See the Sun-God of the ancient Semitic West, Hammu, Hebrew Union College Annual XVIII, 1944, p. 456, notes 146 and 147; see ibid., pp. 469 ff. On the suffix ân/ôn, expressive of the idea of belonging see Noldeke, Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenl. Jesus XV, 1861, p. 806, and H. and J. Lewy, Hebrew Union College Annual XVII, 1943, p. 136 ff. with footnote 500. See now also the observations of Thureau-Dangin, Rev. of Ass. XXXVII, 1940, p. 100; regarding the identity of suffixes expressing either membership or diminutives, see Brockelmann, Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der semitischen Sprachen, Berlin 1908, vol. I, pp. 400 ff., § 221.

[11] As established by Schaumberger, op. cit., p. 318, names like this allude to the slowness of the revolution of the planet Saturn.

[12] For some attestations of this, taken from both biblical and cuneiform sources, see J. Lewy, Revue de l'Histoire des Religions CX, 1934, p. 59 ff.

[13] It would take us too far from our topic to analyze here how this belief was abandoned when the conception of a universal god became generally accepted. Suffice it to say here that it can be traced back to the sixth century BC In the text BM 90920, the so-called Proclamation of Cyrus to the Babylonians, the Persian conqueror of Babylon is depicted as a devoted worshiper of Marduk. The very national god of the Babylonians, so it is reported, guided Cyrus to his sacred city after choosing him to reign over his country. Such a belief can be found in the Book of Jeremiah where the prophet quotes Yahweh speaking of the conqueror of Jerusalem as "Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, my servant" (Jer. XLIII, 10) into whose hands He intended to place the city of Jerusalem (Jer. XXXII, 3). Here again it is assumed that the conqueror who has been called by the patron deity to govern his city is a "servant", that is, a devoted worshiper of this same god.

[14] See, eg, col. III, l. 8 of Sennacherib prism.

[15] See Revue de l'Histoire des Religions CX, 1934, p. 61.

[16] See Journal of Biblical Literature LIX, 1940, p. 519 ff.

[17] On the relationship of the form Šulmânu with the form Šalim see in particular J. Lewy, Nāh et Rušpān, Mélanges Syriens offered to M. René Dussaud, vol. I, Paris 1939, pp. 274 ff., and p. 454 of the text cited above, p. 332., note 10.

[18] See the quote above, note 16.

[19] See col. III, l. 132 of the Annals of Aššûr-naṣir-pal (Budge and King, Annals of the Kings of Assyria, vol. I, London 1902, p. 386): âlKalḫu maḫ-ra šà m dŠulmânu ma-nu-ašarid šar mât Aš-šûr rubû a-lik pa-ni-a êpušuš “the ancient city of Kalḫu, which Šulmânu-ašarid, king of Assyria, a prince who preceded me , built”; see the parallel passage ibidem, p. 184, ll. 6 – 7; p. 219, ll. 14 ff.; p. 244, col. V, ll. 1 et seq.

[20] See p. 63, note 148 of the work cited above, note 8.

[21] See above, p. 332.

[22] For some passages attesting this belief in cuneiform sources see p. 85 with note 243 of the work cited above, note 8.

[23] The fact that Ningirsu, the divine patron of Lagaš, identified himself with the planet Saturn was first highlighted by Morris Jastrow, Jr., Rev. D'Ass. VII, 1910, p. 173.

[24] So in the so-called Statue G of Gudea (col. II, l. 6). For a transliteration and translation see Thureau-Dangin, Die Sumerischen und Akkadischen Konigsinschriften, Vorderasiatische Bibliothek, vol. I, Leipzig 1907, pp. 84 et seq.

[25] See, eg, Gudea cylinder B (Thureau-Dangin, op. cit., pp. 122 ff.), col. V, l. 15.

26 A-ḫuš-gi4-a; see, eg, A cylinder (Thureau-Dangin, op. cit., pp. 88 ss), col. VIII, l. 15; with the. IX, l. 20.

[26] A-ḫuš-gi4-a; see, eg, A cylinder (Thureau-Dangin, op. cit., pp. 88 ss), col. VIII, l. 15; with the. IX, l. 20.

[27] As always, the name of the work is taken from the first verse of the first tablet. The first to draw attention to its importance was Hroznӯ, MV AG VIII, 5, 1903.

[28] As we learn from the New Year ritual celebrated in the city of Babylon in honor of its patron-god, Marduk (see Thureau-Dangin, Akkadian rituals, Paris 1921, p. 136, ll. 280 - 283), according to which during this feast the priest-urigallu recited theEnûma Elish, the story of Marduk's victory over Tiâmat and the consequent creation of the world, we will not fail to hypothesize that in Nippur, where Ninurta enjoyed a high rank among the local deities, the epic which recounts his heroic deeds and the subsequent creation of the first city after the flood was recited during a festival celebrated in his honour. This conclusion is the most well-founded of all, since theEpic of Ninurta itself, in tablet I, ll. 35–36, mentions Ninurta merrily celebrating a festival instituted in his honor. (We count the lines according to the numbering established by S. Geller, Die Sumerisch-Assyrische Serie LUGAL-E UD ME-LAM-BI NIR-GÁL, Altorientalische Texte und Untersuchungen I, 4, Leiden 1917, where the relevant passage is found on p. 279. In Kemal Balkan's most recent commentary and translation of tablets I, X, XI, and XII, [Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakültesi, Sumeroloji Enstitüsü Neṣriyati no. 1, Istanbul 1941, pp. 881-912], the line in question, on p. 907, bears the number 18).

[29] See in particular the fragment K. 5983 (Geller, loc. cit., p. 316) and tablets II and III, where it is said that Ninurta's devotees did not know where to go when the walls collapsed (?) under the pressure of the raging deluge; the birds were knocked to the ground, probably by a severe storm (cf. the mention of Adad, the god of the atmosphere, in tablet III, ll. 7 – 8), and the other animals were also threatened with extermination. Ninurta himself was forced to use a raft to reach the battlefield.

[30] See previous note.

[31] That this is the idea behind the intervention of the stones in the battle becomes particularly clear by reading ll. 7 – 14 of tablet X (according to the numbering of Geller, loc. cit., p. 295; ll. 4 – 7 (p. 908) in Balkan's translation), where it is reported that Ninurta cursed the stones-šAmmu for they had risen up against him in the mountains and menaced him in his lofty abode. A rock, carried away from a nearby mountain, had apparently crashed into Ninurta's temple.

[32] See tablet III, ll. 13 - 14 (Geller, loc. cit., p. 284). We read the corrupted word at the end of line 14 i[k]-si-ir-šu, since the verb kasaru it is used elsewhere in reference to damming rivers and streams.

[33] Tablet VIII was reconstructed from various fragments by Langdon, Babylonian liturgies, Paris 1913, No. II, pp. 7 – 11. Although not identified by the usual colophon, the signature line at the end of the piece makes certain its place in the whole series.

[34] See ll. 23 – 24, of the text as reconstructed by Langdon, and cf. Landsberger, Journal of Near Eastern Studies VIII, 1949, p. 276, note 91.

[35] Landsberger (Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakültesi Dergisi, vol. III, no. 2, 1945, p. 152 ff.) thinks that "he (ie Ninurta) piles up the stones taken from a mountain, gives them to his mother Ninlil and gives her the name 'Mistress of the Mountains'". There is no element, however, in the remaining portions of the poem, which supports such a claim. On the contrary, various passages of our text make it clear that, when speaking of gu-ru-ni što ag-ru-nu or similar (see, eg, tablet IX, ll. 38 - 39 [Geller, loc. cit., p. 292]) the author of the work refers to the walls and buildings of the new city and not to a mountain, assuming that the existence of mountains and plains, of course, predates the first post-Flood settlement. We are referring not only to the aforementioned lines of tablet VIII (Langdon, op. cit., pp. 8 – 9) which clearly speak of Ninurta heaping stones for the building of a city, but also to tablet XIII, ll. 24 – 25 (Geller, loc. cit., p. 312) where the poet speaks of the “new city built” as the kingdom of Ninurta's mother, Ninḫursag, the goddess of the earth. – It is not without interest to recall in this context Gen. X, 8 - 12, where Ninurta (Nimrod) is represented as a builder of cities, including Kalḫu, the holy city of Saturn in the Assyrian territory (cf. above, p. 333 with note 19).

[36] In the following pages we quote Sanchoniathon-Philo of Byblos according to the edition of Carl Clemen, Die Phönikische Religion nach Philo von Byblos, Mitteilungen der Vorderas.-.Egyptian Jesus, vol. 42, 3, Leipzig 1939, pp. 16 ff.

[37] Although the name Elos makes it perfectly clear that the entity thus qualified was a superior god, the surviving text represents Elos-Kronos as a human king deified after death. Here we encounter the well-known tendency of Greek authors to depict the ancient gods as human beings who were posthumously paid divine honors. A similar trend can be found in the Bible. As was suggested by J. Lewy (Revue de l'Histoire des Religions CX, 1934, p. 45), the Laban hâarammi of Gen. XXIV ff., half-brother of Isaac and stepfather of Jacob, was none other than the Moon-god, the divine lord of Ḥarrân, who, in the region of Mount Lebanon, was revered under the name of Laban (on the report of this divinity with Mount Lebanon see especially J. Lewy, The Old West Semitic Sun-God ḤAmmu, Hebrew Union College Annual XVIII, 1944, passim). Muslim writers, for their part, frequently portrayed pre-Islamic Arab gods as deified human beings. As an example we report the stories of al-Mas'ûdî (Les prairies d'or, vol. III, Paris 1917, p. 100 ff.) around Isâf and Nâila, the gods worshiped together with Hubal (see below, note 54, sub 1) in the Ka'aba of Mecca. In all these cases, men who, while not believing, or no longer believing, in the existence of these ancient gods, had to deal with the persistence of the mythical legends that remained in popular memory, transformed the ancient gods into human beings and thus preserved the old stories and legends as part of popular folklore.

[38] See Clemen, op. cit., p. 31, sub 44.

[39] See Clemen, op. cit., pp. 25 ff., Sub 16 - 18. However, while in the Babylonian myth his father is the god of winds and atmospheric phenomena Enlil, Saturn, in the Phoenician myth, is the son of Uranus, the god of the sky.

[40] In Phoenician myth, he is the same father of Saturn, Uranus, against whom he fights and from whose throne he finally drives him. The authenticity of this feature is proved by the fact that also an Arab version of the Nimrud myth reports that Nimrud (ie Ninurta; cf. above, note 35 in end) defeated and dethroned his father (see Moritz Weiss, Kiṣṣat lbrāhīm, Dissertation Strassburg 1913, p. 1 - 8). According to this conception whereby, as usual in Arabic literature, the ancient gods are represented as human beings (cf. above, note 37), Ninurta's father is warned in a dream that his son would kill him inheriting the throne. So then he gives orders to kill his son immediately after his birth, but his mother saves him. Ninurta grows up without knowing his parentage and finally defeats and slays his father, seizes the throne, and places all the earth under his rule.

In Nippur where, as aforesaid, theSumerian epic of Ninurta originated, a story like this could go unmentioned, for in this city Ninurta and his cult never supplanted the older cult of his father Enlil, who remained the chief deity of Nippur throughout the period that can be traced of that city's religious history, meaning up to the Seleucid period. It is therefore clear that the epic of Nippur could not recall Ninurta's father, Enlil, as a god defeated and dethroned by his hero. However, the possibility cannot be excluded that the Sumerian version was also adapted to local conditions on the basis of a myth in which Ninurta's enemy was his father. Because we know from the Babylonian flood myth that it was Enlil himself who conceived and carried out the intention of unleashing a flood in order to annihilate all life on earth. Thus the deluge against which he fought in the Nippur epic, in the original version, may also have been caused by the moody storm and weather god Enlil, although, for the reasons outlined, no mention is made in the extant poem of the deity who had sent the flood. In fact, when theEpic of Ninurta (however repeatedly calls his hero "the son of Enlil") speaks of Ninurta as "He who sat not with a nurse" and "the scion of (and the like) - My father whom I do not know -" (see tablet I , rev., ll. 7 - 10, Geller, loc. cit., p. 280; p. 907, ll. 28 - 29 of the Balkan translation), the Arab legend of Nirmrud comes to mind in which Ninurta-Nimrud after having been suckled by a tiger he grew up not knowing who his father and mother were.

[41] See Clemen, op. cit., p. 26, sub 19.

[42] Clement, op. cit., p. 30, sub 35.

[43] See Clemen, op. cit., p. 16, and p. 31, sub 44.

[44] See Clemen, op. cit., p. 29, sub 33, and p. 32, sub 44.

[45] See Bezold and Boll, Sternglaube und Sterndeutung, Aus Natur und Geisteswelt, vol. 638, Leipzig 1919, pp. 60 ff.

[46] See his Kitâb nuḫba al-dahr fî 'agâ'ib al-barr w'al-baḥr, and. Mehren, St. Petersburg 1866, p. 40.

[47] As will be reported in greater detail below, Fr. 343, the characteristic shape of a temple of Saturn was that of a cube.

[48] For references in cuneiform literature see Schaumberger, op. cit., p. 317. As Schaumberger notes, "Saturn is called the black or dark planet because it actually usually appears dimmer or less bright than the other planets." With regard to medieval sources, see, eg, al-Bîrûnî, Kitâb at-tafhîm, and. R. Ramsay Wright, London 1934, p. 240.

[49] Les prairies d'or, vol. IV, Paris 1914, p. 44.

[50] See, eg, al-Mas'ûdî, Les prairies d'or, vol. IV, p. 46. aš-Šahrastânî (translated by Th. Haarbrücker, vol. II, Halle 1851, p. 340) reports that Hubal, the greatest of the Arab gods, had his seat on the roof of the Ka'ba. Ṭabari (Annals, and Leiden, vol. I, 3, 1881-1882, p. 1075), on the other hand, reports that Hubal was placed inside the Ka'aba and placed at the mouth of a well. Certainly, our sources are unanimous in qualifying Hubal, in the same way as other Arab idols, as non-Arab, idol worship being, in their view, an institution borrowed from Syria in a relatively late period (see , eg, al-Mas'ûdî, Les prairies d'or, vol. IV, pp. 46 ff., and cf. Wellhausen, Remains arabischen Heidentums, Berlin and Leipzig 1927, p. 102, which declares: "Idols are not properly Arabs, vathan e canam they are imported words and imported things”. However, from cuneiform inscriptions such as, eg, the prism of Aššûr-aḥ-idinna Th. 1929-10-12, 1 (published by Thompson, The Prism of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, London 1931, pl. I - XIII and pp. 9-28), col. IV, ll. 1 – 14, we learn that from his victorious campaigns against Arabia, the father of Aššûr-aḥ-idinna, Sîn-aḥḥê-erîba, brought six Arab deities (among which dA-tar-sa-ma-aa-in, “Ishtar of the Heavens”); at the request of Ḫazâ'il, king of the Arabs, Aššûr-aḥ-idinna restored these gods to his worshippers. Thus it is clear that in the early eighth century BC, the Arabs represented their gods, and more precisely their astral deities, by means of images which could be carried back and forth from Nineveh by the Assyrian kings. That these images were, like those placed in Assyrian and Babylonian temples, anthropomorphic statues and not stones or rocks is particularly clear from the text K. 3405 of Aššûr-bân-apli (transliterated and translated by Streck, Ashurbanipal und die letzten assyrischen Könige bis zum Untergange Niniveh's, vol. II, Leipzig 1916, pp. 222 ff.), according to which the Assyrian king, when he returned for the second time the "Ištar of the Heavens" (reported there under the names of Dilbat and Ištar) to his Arab worshippers, gave her a gold comb set of gems (for mulṭu<mušṭu, “comb”, see Meissner, Archive für Orientforschung V, 1928-29, p. 183 ff., and in particular VI, 1930-31, pp. 22 ff., which duly points out that, according to an Assyrian ritual text, the Assyrian Ištar also received a golden comb as a gift). It is therefore legitimate for us to consider Hubal and the other Arab deities represented by idols as genuinely Arab, all the more so as the legend about the importation of these gods from Syria can easily be explained thus: when the Muslims adopted the belief that the Ka'aba had been built and dedicated by Abraham to his son Ishmael, it became necessary to find an explanation for the fact that, before Muhammad, the worship of the idol of Hubal and not the worship of the aniconic god of Abraham was practiced in the famous ancient sanctuary.

[51] As well known (cf. Brockelmann, Grundriss I, p. 336) the semantic formations qutal they are adjectives which indicate that the action expressed by the relative verb was performed in a violent way. – Manifestly under the influence of the legend mentioned above (see previous note) about the Syrian origin of the idol, Hitti (History of the Arabs, London 1937, p. 100) proposes to derive the name Hubal from Aramaic and to translate it with "vapour", "spirit". However, he is not at all concerned with explaining the semantic form qutal, nor does it explain how, in his vision, an intelligent people would come to attach a name like this to an image made of stone and metal.

[52] See Annals of Ṭabarî, Leiden edition, vol. I, 3, 1881-1882, p. 1074. 53 See p. 339.

[53] See p. 339.

[54] Wellhausen, in his speech on theḤağğ di 'Arafa (op. cit., pp. 79 ss.) never mentions it. Neither he nor he attempted to interpret the "remnants of Arab paganism" preserved in the ritual of that festival in the light of the information provided by cuneiform sources on the most ancient Semitic religions. As it would lead us too far from our subject to discuss here in detail the reason which makes it clear that the pre-Islamic cult of Mecca was one of the astral religions practiced by the Semites throughout the ancient Near East, we mention only those correspondences which may have some bearing on the subject of this writing:

(1) Hubal, the chief deity of Mecca, was not the only god worshiped in the Ka'aba. In addition to several of his daughters, our sources often mention a divine couple, Nâila and Isâf, who, according to aš- Šahrastânî (Haarbrücker, op. cit., II, p. 340) were venerated on the hills of Marwa and Şafa, overlooking the sanctuary. How the Assyrian and Babylonian planetary deities were worshiped together with their divine families (as relevant examples we mention Ningal, Nusku and Sadarnunna, respectively consort, son and stepdaughter of Sîn, who, according to col. II, l. 18 of the cylinder inscription of Nabû-na'id BM 82, 7 – 14, 1025 [transliterated and translated by Langdon, Die Neubabylonischen Königsinschriften, Vorderasiatische Bibliothek, vol. IV, Leipzig 1912, pp. 218 ff.] and col. II, l. 13 of his so-called inscription of Eski-Ḥarrân [ibidem, pp. 288 ff.] were worshiped together with Sîn in theEḫulḫul of Ḥarrân), we will not fail to conclude that Nâila and Isâf were considered close relatives of Hubal. Since in Nippur the planet Saturn was worshiped jointly with his parents, and since, as aforesaid, both in theSumerian epic of Ninurta, both in the mythological legend handed down by Sanchoniatone, the mother of Saturn, the goddess of the earth, played an important role, we can further deduce that the divine couple of Nâila and Isâf were believed to be that of the parents of the deity at the head of Mecca. We can even hazard a guess about Hubal's consort: In cuneiform literature, Ninurta's wife, Gula or Bau, is often referred to as "the great healer" (for references see Tallqvist, Akkadische Götterepitheta, Helsingforsiae 1938, p. 5); since the Muslims attribute to the bitter water of the well of Zemzem, located in the courtyard in front of the Ka'ba, the power to heal all sorts of diseases, we can legitimately conclude that this well represented the healing goddess, the consort of Saturn.

(2) Accounts by Muslim writers indicate that the Ka'aba housed not only the statue of its tutelary god, Hubal, but also three hundred and sixty idols with it, all destroyed when the prophet conquered Mecca (for some references see Wellhausen, op. cit., p. 72). There is no reason to doubt (with Wellhausen) the correctness of this information, since he recalls a statement by ad-Dimišqî (op. cit., p. 42) according to which the temples dedicated to the cult of the Sun contained numerous statues made of wood, stone, or metal which, placed around the image of the sun-god, were said to represent the ancient kings of the respective cities of the region. That those images were not, however, a characteristic of the temples of the Sun, is proved by the fact that in the archaic temple of Ištar in Mâri, the statue of the goddess represented by the planet Venus was found by archaeologists surrounded by the images of kings and high personages in attitude of devotion (see A. Parrot, Mari, a lost villa, Paris 1936, pp. 89-92). The purpose of these statues is well illustrated by the inscription on an archaic statuette from Lagaš in which the mother of one of the governors of this city states that she placed her image near the ear of her divine lady so that she could address prayers to the goddess (see Thuerau-Dangin, op. cit., pp. 64 ff., sub f). Equally enlightening is the information contained in col. II, ll. 9 ff. and 22 ff., of the Sippar Nabû'na'id cylinder inscription BM 81-4-28, 3 and 4 (transliterated and translated by Langdon, op. cit., pp. 252 ff.), in which the Babylonian king declares that, as a manifest sign of continued devotion to the Sun-god, he placed a portrait of himself (šalam šarrûtiia) in the sanctuary of Šamaš in Sippar; this statue had the manifest purpose of representing him before his god when his official duties prevented him from personally paying homage to the divine lord of Sippar. If therefore kings, queens and other high dignitaries continued for centuries to place their effigies in the temple next to the image of their divine lord or lady, it will not surprise that, as is reported around Mecca, three hundred and sixty statuettes surrounded that of the god. Since Muhammad rejected the idea of representing any living being in an image, whether animal or human, his followers destroyed, together with the statue of Hubal, the effigies with which their previous kings had expressed their devotion to the god. patron saint of Mecca.

(3) The famous pilgrimage of 'Arafa (cf. Wellhausen, op. cit., pp. 79 ff.) bears all the characteristic aspects of the Assyro-Babylonian feast of theakitu. As is well known, these festivities centered on a procession of the statue of the god from its main abode to a peripheral sanctuary, with transfer effected partly by cart, partly by raft. As is known in particular from the ritual ofakitu of Ḥarrân as preserved by an-Nadîm in his Kitab al-fihrist (ed. Flügel, vol. I, Leipzig 1871, p. 325, ll. 23 ff.), the festival culminated when the citizens, both male and female, went out en masse to await the return of the god in their midst (a detailed analysis of the ritual ofakitu of Ḥarrân will be published by the writer in a forthcoming study on the religion of Ḥarrân). A popular procession of this kind, interrupted by repeated "waiting stops", still has a predominant role today in theḤağğ towards Minâ and 'Arafa. Furthermore, just like in Ḥarrân the procession followed the course of the Balîḫ up to the temple of 'akitu in the city of Dahbâna, pilgrims from Mecca proceed along the bed of the stream which connects Minâ and 'Arafa with the valley of Mecca; from which it is reasonable to conclude that in the pre-Islamic period the raft carrying the statue of Hubal traveled up this river as far as 'Arafa (that, at least at certain times of the year, this stream contained enough water to keep a raft, results from the account of its overflowing as reported by TF Keane, Sex Months in Meccah, London 1881, p. 177). Further attention must be drawn to the fact that in Ḥarrân, as well as in other Assyrian and Babylonian communities, one of the main themes of the feast ofakitu it was the mortification and self-punishment of the worshipers followed by a reconciliation with the deity; a theme which, as far as Ḥarrân is concerned, is expressed with particular clarity by the name attributed by medieval sources to the temple of theakitu out of Ḥarrân. As this name, derived from the Akkadian verb salamu, “to reconcile”, has the meaning of “Reconciliation of Sîn” or “Reconciliation with Sîn”. That the same theme played a part in the Meccan festival is evident from the name "Day of Forgiveness" of the ninth day of the month of Du'l Ḥiğğa,the first day of the Pilgrimage (see al-Bîrûnî, Kitâb al-âtâr al-bâqiya and. Sachau, Leipzig 1878, p. 334) and by the custom of today's Muslims to confess and forgive all past sins after their arrival in Minâ (see Keane, op. cit., pp. 143 ff., according to which the second day of the Pilgrimage was the day on which the pilgrims "were to be absolved of all their past sins").

[55] D'Herbelot (Bibliothèque Orientale, ou Dictionnaire Universel, vol. I, La Haye 1777, p. 433) reports a tradition according to which "the mystical doctors" among Muslim scholars define the Ka'ba as "the first which God built". It will be noted that this tradition is even closer to the aforementioned legends from Nippur and Byblos of Syria than the usual Arab story which mentions Adam and Abraham as the two consecutive builders of the Ka'ba.

A comment on "Origin and meaning of Mâgên Dâwîd – Hildegard Lewy (part I)"