Through the revelation of doctrines such as the eternal return, the death of God and the transvaluation of values, Nietzsche undertakes to show us how only by understanding history as something alive and which constitutes us insofar as we are already always inserted in a historical world, we can have before us a future that is a Future, therefore a future herald of History and not of mere random events.

di Mariachiara Valentini

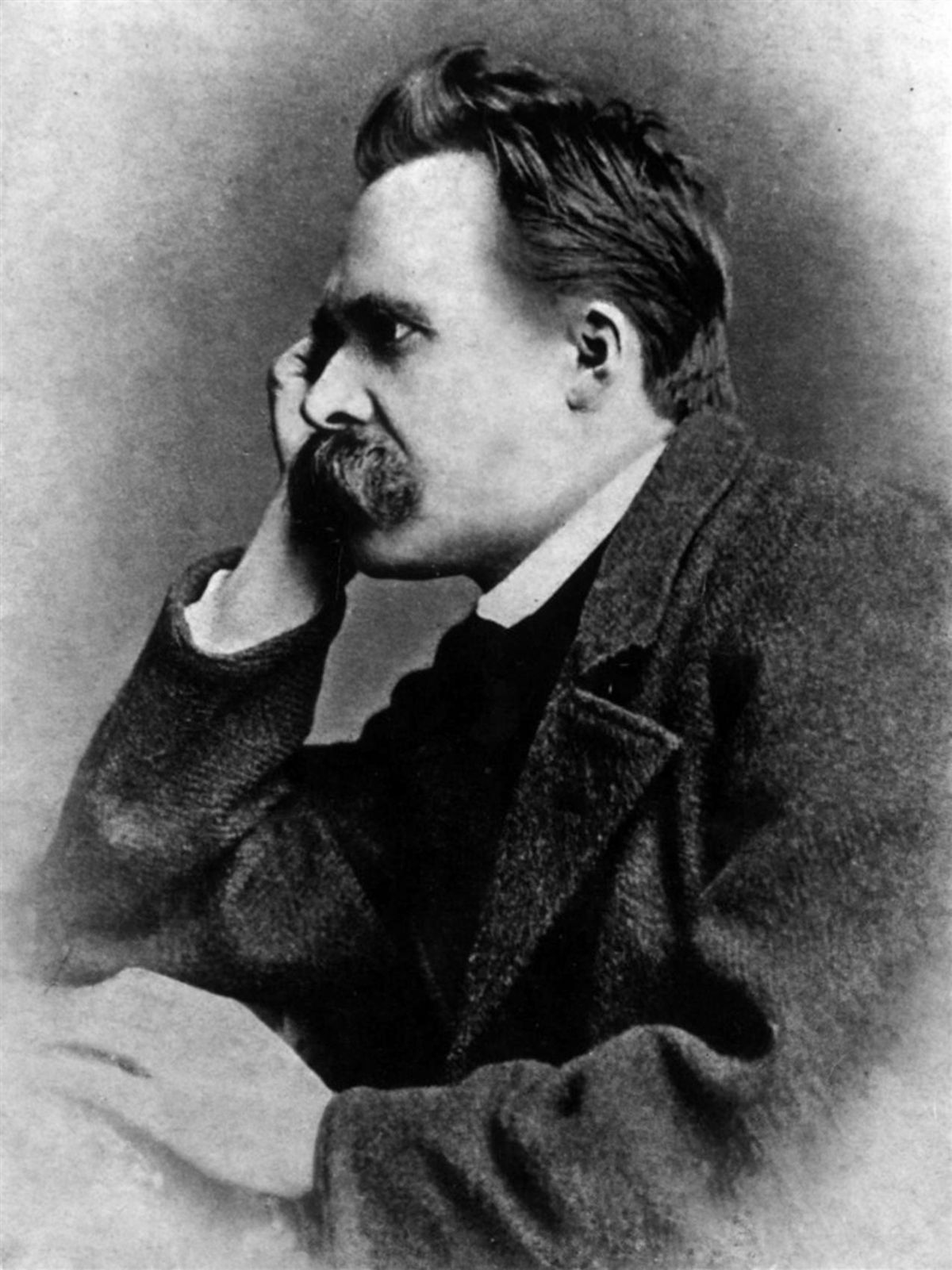

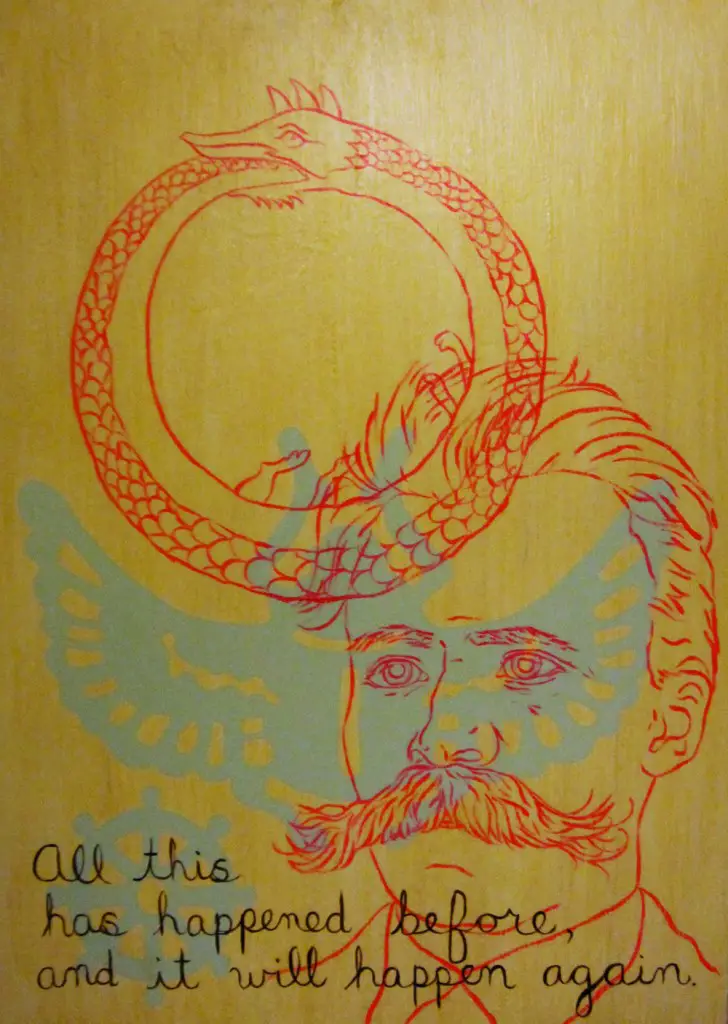

cover: Edward Munch, "portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche"

Fascinating and often elusive to our understanding, the Nietzschean concept of eternal return it still seems to take on an infinite series of interpretations that try to reduce it to the classical categories of metaphysics, trying to refute it by subjecting it to the laws of logic, to deconstruct it and in this way to make it the mark of the insoluble contradiction of Nietzsche's thought.

In order not to get lost in forced interpretations that have already been extensively traveled (we do not intend to adhere, here, to any of the interpretations provided by the critics to date), it is necessary to start our investigation starting from the fact that in the development of the Nietzsche's thought concepts tend to change over the years, sometimes even after a short time (think for example of the concept of the will to power, which undergoes several changes periodically every three or four years).

The fundamental concepts of Nietzschean philosophy (the transvaluation of values, the eternal return, the will to power, the essence of truth, the superman) they are such that they can never be considered in isolation by abstracting them from their whole, but only within the necessary co-belonging that sees them involved, against the background of the original evidence that for Nietzsche is constituted by becoming.

Giorgio Colli, philologist and curator of the Kritische Gesamtausgabe, the edition of Nietzsche's complete works, invites us not to forget that Nietzsche was born as a philologist, and that his philosophical reflection takes shape precisely starting from meditation onGreek essence of the Dionysian and consequently on what led to the birth of the tragedy. Although the Nietzschean interpretation of Heraclitus and of Greek wisdom in general is at times superficial, the influence that the mystery cults and the thinking of what we commonly call i pre-Socratics (a term that actually lends itself well to the context of our investigation, given that Nietzsche sees the origin of morality in the figure of Socrates) have exercised on Nietzsche, when he has ascertained becoming as original evidence.

To indicate the real as becoming means to unmask the fact that everything that presents itself to us as something "stable" is a mystification (or rather, a crystallization) carried out by man who intends to find an anchor in the flow of all becoming, in order not to be overwhelmed by it - or, to put it expressly in Nietzschean terms, a "condition of survival and growth".

We immediately see how in itself the concept of becoming implies such unmasking, as it is only through unmasking (which takes place through an accurate anthropological, psychological, philological, metaphysical, biological investigation - such as to extend to everything that man calls "The real") that Nietzsche can come to see what is the ultimate foundation of the whole, covered by the centuries-old calcareous stratifications made by the man who tried to to appropriate tooth and nail of a "place in the world": becoming.

Nietzsche thus realizes that the concept of subject is a fiction (which is also foreign to Greece), which found its most meaningful formulation in the modern age with the thought of Descartes, and that consequently thought (precisely starting from its being conceived as res cogitans) is likewise a fiction based on an interpretation that man has given on the basis of "elements whose connection, whose causality is completely hidden from us" (fragments 1887): and therefore also the object, this we call what (das Ding), is an arbitrary schematization. The pinnacle of this attempt by man to secure reality is the concept of truth, for Nietzsche "a kind of error without which man could not live": once again it is the arbitrary creation of a stable point of reference to which to refer all that is and what happens. On these conceptual concretions man has built logic, and with it the various laws of thought, including the principle of non-contradiction and the principle of individuation.

This spasmodic search for stability, a sort of vocation originating from a state of necessity, already starting from Plato leads to the formulation of a stable and true world as opposed to the fleeting mutability of what surrounds us and to the identification of a first and absolute principle (absolutus, thus freed from any link with what appears) that constitutes the foundation of the whole. And Plato himself will be seen by Nietzsche as the proponent of the first step that leads to the concept of the Christian God, who is nothing other than the stabilization, the definitive schematization of the first cause as Summum Ens, the foundation of Being and of all entities.

But if this is the case for Nietzsche, this means that Being too (as dialectically opposed to Becoming) is a schematization: man's radical attempt to abstract from the mutability of becoming what remains, indicating it as reality (and condemning the becoming to the rank of mere appearance) precisely inasmuch as it does not change. The transvaluation of all values is thus completed: with the death of God, the veil of all appearances has been torn off. It does not automatically follow from this that man is ready to grasp the Truth (this time understood in a genuine sense, and therefore as a recognition of becoming): Nietzsche has strong doubts on this front - he expects to remain the only one to dwell in this recognition for a long time - and it will not be surprising if our philosopher never tired of calling himself a loner (a metaphysically lonely) and an outdated.

Recognizing Becoming as original evidence does not, however, mean having definitively closed the accounts with Being: the traditional conception of becoming understands this concept as a "going in and out of nothing" by all things, and in so doing he founds becoming on nothing. For Nietzsche this is obviously unacceptable, since first of all, if becoming is the ultimate foundation of all things, it cannot in turn be founded on anything else, and secondly because this conception continues to maintain firm the distinction between a "real world ”And an“ apparent ”one that had already fallen with the critique of values and the concept of value.

The question, posed in modern terms, could then sound like this: if the whole is becoming, if there is no permanent Being, how to save things from nothing? Nietzsche shows us how the consequential becoming-null implication is also a mystification, since becoming does not exclude persistence, but on the contrary in a certain sense requires it. This request is not a satisfaction of the need for human stability, but resides in the very essence of becoming, and is shown in all its evidence with regard to Time.

It is customary to consider time universally divided into past, present and future, with a finished history that is now behind us, as if dead, an elusive present and an unknown future dominated by chance. However, this triple subdivision, it must be remembered, is the result of a human interpretation aimed at determining the location of events in time: and the chronological subdivision is essentially linear. Precisely starting from the meditation on the problematic nature of considering history as a "dead thing" (delegating it to a mere object of historiography) Nietzsche's youthful reflection on the burning question of relations with the past originates (F. Nietzsche, 1874, On the usefulness and harm of history for life): in the second Inactual Consideration, in fact, Nietzsche undertakes to show us how just meaning the History as something alive and which constitutes us as we are already always inserted in a historical world, we can have before us a future that is a Future, therefore, a future herald of history and not mere chance events.

Having a historical vision means knowing how to accept chance, and not simply enduring it, suffering it while remaining helpless and at the mercy of necessity. But if the past, as history, is something that always surrounds the essence of man, it cannot be downgraded to a mere calculation and account of what has happened, which no longer exerts any influence on what is and what is to come. . Understanding it in this way, that is in a historiographical sense, once again means making a schematization, fixing what happened once and for all, and transforming it into a dead thing. At this point we can realize that Nietzsche's transvaluation of values also includes the concept of the past, and consequently the concept of time in general: this means first of all freeing the essence of time from the chronological-linear schematization.

This delicate move is made very slowly by Nietzsche, unlike all the others: it looks timidly as a hypothesis The Gaia Science (published in 1882), together with the character of Zarathustra, only to find its development in the work dedicated to the prophet (1883-1885). In the famous aphorism 348 Nietzsche presents us with a very peculiar possibility, through the mouth of a demon who stealthily crawls and whispers in the ear (a demon that is too reminiscent of the Socratic δαίμων):

“This life, as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live it again and again countless times, and there will never be anything new in it, but every pain and pleasure and every thought and sigh […]. "

We are faced with the first explicit formulation of the eternal return. And in response to this hypothesis, Nietzsche asks man a capital question:

“If that thought took you into its power, to you, as you are now, it would undergo a metamorphosis, and perhaps it would crush you; the question you would ask yourself every time and in every case: «Do you want this again and again countless times?» it would weigh on your acting as the greatest burden! Or, how much you should love yourself and life, not to to desire more anything other than this last eternal sanction, this seal? "

Here we will leave out Nietzsche's interesting literary expedient (which here presents the eternal return as a personal matter, in which one's own being, one's life is at stake - starting therefore from the consequence to arrive at the cause), to focus on what Nietzsche himself considered his fundamental intuition, and at the same time his most abysmal thought. Contrary to what this single aphorism leads us to suppose, Nietzsche repeatedly in subsequent works and in all esoteric writings relating to this period (the posthumous fragments 1883-1887) states that the concept of eternal return cannot be understood in an exclusively private sense, but in a universal one: every action performed by every man in every moment of history is destined, sooner or later, to repeat itself.

We have said that the eternal return was for Nietzsche an intuition, a sort of dazzling illumination: and unlike the other constitutive concepts of his thought, Nietzsche presents it to us as a real doctrine (and the very choice of this term makes us perceive it as something necessary and ineluctable), whose explanation will be precisely the task entrusted to Zarathustra. And for Zarathustra himself, the eternal return will be something problematic: it is a vision and an enigma - "the vision of the most solitary of men". In this evocative passage of Thus spoke zarathustra, Nietzsche introduces us to the prophet accompanied by spirit of gravity in the form of a dwarf (representing all the "stable" and "immutable" created by man, which "pull down" Zarathustra on his way up the mountain), which suddenly stops in front of a scenario unusual - such as to leave him unable to utter a word for several days: the two stop in front of one driveway door, and precisely at this point the spirit of gravity descends from the shoulders of Zarathustra, who finally claims to feel lighter:

“Two paths converge here: no one has ever walked them to the end.

This long way to the door and back: it lasts an eternity. And that long way out the door and on - it's another eternity.

These paths contradict each other […]: and here, at this carriage gate, they converge. At the top is written the name of the door: 'moment'. "

Two eternal paths, which seem to go in the opposite direction (and therefore contradict each other) but which converge inmoment (Augenblick): the past and the future. They they seem contradict themselves, as well as they seem continue in a straight line into the unknown, but things are not really that way - and it is not Zarathustra who realizes it, as we might expect, but the dwarf, who enigmatically states that "Every truth is curved, time itself is a circle". To these words Zarathustra at first reacts horrified, but continuing to observe the scenario that surrounds him begins to wonder:

“Any of the things that can walking, must he not have already traveled this path once? You won't have to each of the things that can happen, have already happened, done, passed once? [...] And all things are perhaps not tied tightly to each other, in such a way that this moment draws behind it all things in the future? Therefore - - even himself? "

Zarathustra's long monologue is nothing more than an argument made aloud, a reasoning that stumbles from question to question until it reaches intuition. The eternal return is therefore told by Nietzsche in the same way in which he presented himself to him for the first time.

Probably the doctrine of the eternal return was really conceived by Nietzsche as something that 'awakens', as it was instantly understood by him: let's turn again towards the demon de The Gaia Science, which suddenly reaches the ear, or to Zarathustra (the awakened one!), who bestows his teachings as an old man, or to his disciples, who are indeed men in the middle of their own life, ready to accept the teachings of the prophet.

Only if I already know, I have tried on my skin, what a "so it was" is, can I transform it into a "so." I wanted it to be ". Man must already have experienced the error and the sufferings that derive from it, in order to be able to decide to free his will as a will to power, and therefore as a creator, to ensure that at least from the moment in which awareness takes place the coincidence between 'so it was' and 'so I wanted it to be' may be perfect (and already ne The Gaia Science Nietzsche asked: “What makes heroic? Moving towards one's supreme pain and one's supreme hope "). However, this does not mean that the acceptance of the past is a stretch - it must be really wanted because we must want its repetition: will to power in fact means wanting to become what one is; but everything that has been, however much it has been lived in the blindness and illusion given by metaphysical-moral thought, has made us exactly what we are now, and not wanting this "so it was" would therefore mean not wanting ourselves, not wanting a part of that whole that we are.

Nietzsche's can be configured as an invitation to transform oneself and one's life, but it cannot be understood in a moral sense: the sense is always metaphysical. One wonders how the metaphysical sense can be founded if the eternal return is something learned and not already-always-known by man. First of all, 'not knowing' does not and cannot imply the 'not being' of something. Indeed, the fundamental problem that moves Nietzsche's thinking is connected to these questions. The transvaluation of values, the destruction of the true world, the death of God are processes that liberate man precisely from what was already-always-known, from eternal and immutable truths., and this liberation, which leads to the doctrine of eternal return, necessarily leads to liberation from that eternal and immutable constituted by all that man thought he knew.

We could venture the hypothesis that the destruction of eternal and immutable truths must also happen again and again, and this in every single man, because if this destruction and together with the doctrine of the eternal return became 'always-already-known' by the man, with this they would themselves be eternal and immutable truths, they would be transformed into new assimilation schemes as conditions of survival and growth. For the same reason we believe that one cannot "be born a superman", but only become one. You "become what you are" (Ecce Homo, 1888). It is in fact the learning of the eternal return that implies the transformation of man in the case in which the doctrine is recognized and accepted, and it is this choice between the disavowal and the recognition of the doctrine that leads to remain one of the "last men"Or to become superman. Übermensch, superman, is not an ultra-powerful man, but rather a man set free from its chains that it can finally unfold its essence.

It could also be considered as a sort of myth, an ideal to strive for in the ancient (Greek) sense of the term, an invitation so that humanity can finally get out of the state of decadence in which it has been raging for decades, and which nevertheless must live. on himself to the end, an exhortation that man transforms himself in the same way as Dionysus. It is certain that the superman cannot be understood in a "technical" sense (as Martin Heidegger argued for example), just as it is not technically understood that which continually founds (creates) the superman, that is, the will to power. Nietzsche's will to power, in fact, it is not conceived to be expressed in 'things' and in calculation (we recall how Nietzsche's intent is precisely to oppose the calculating tendency, in favor of a man who is a creator and not a calculator). It it is the foundation that man perpetually gives himself, as becoming, within the whole that is becoming.

With the thought of the eternal return Nietzsche therefore saves things from nothing, guaranteeing the permanence of becoming. And this perpetual self-foundation of man makes it possible to reconcile the need for stability with the original evidence, without the need to resort to the old tendency to schematize, to crystallize, despite the fact that the "supreme will to power" coincides with a sort of survival instinct and conservation, a conatus essendi Spinozian whose sole purpose is to "To impress the character of being on becoming" - this character, precisely because it cannot be simplistically eradicated, goes transformed (and in the transformation maintained as a dialectical element): and indeed "That everything returns, it is the extreme approach of the world of becoming to that of being" [1887]. The extreme approach, which can never be resolved in a coincidence, as it would be an attempt similar to squaring the circle.

8 comments on “Abyssal Thought: Friedrich Nietzsche and the Eternal Return"