The Garden at 19pm (1910) by Edgar Jepson, who lived between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, is presented as a pseudo-sequel to Great God Pan by Arthur Machen, who was a close friend of Jepson: a folk-horror novel set in Edwardian London that was also appreciated by Aleister Crowley, just published in Italy by Dagon Press.

di Marco Maculotti

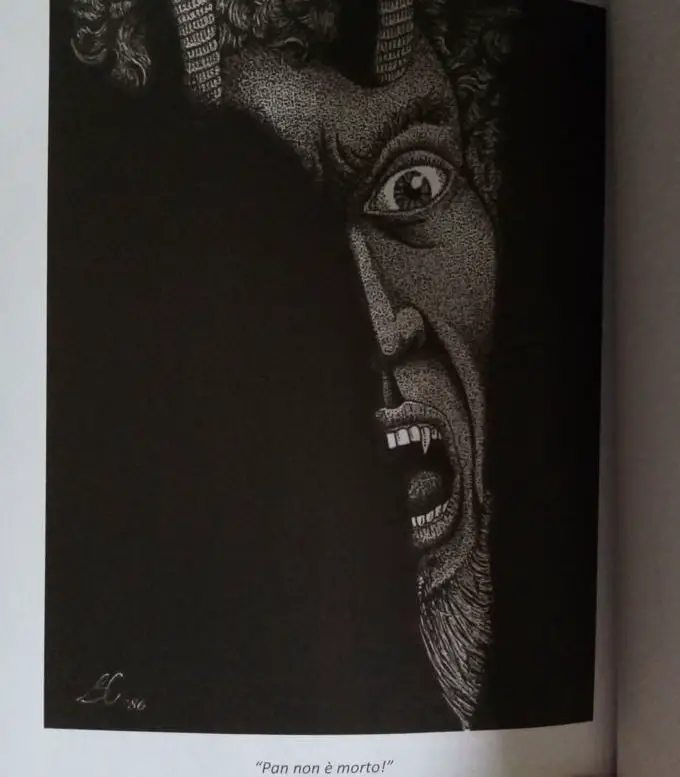

There was a pause; then she cried out in a tone in which triumph mingled strangely with fear: "Pan is not dead!"

He shivered, shuddered, and the room quickly became bright. Her dead face was radiated with triumphant exaltation.- E. Jepson, The Garden at n.19, Postal Code. XXIV

Among the countless recent publications of the small publishing reality Dagon Press - which we have already talked about on our pages and which without a shadow of a doubt we will return to in the future - it is impossible for the writer, given the veneration felt towards the literary work of Arthur Machen, do not welcome the Italian translation of The Garden at 19pm (1910) by Edgar Jepson (1863 - 1938), who was a close friend and great admirer of the Welshman, as well as, above all in this one novel, to some extent imitator. The Garden of n. 19, in fact, it appears right from the start as a tribute to Machen's first folk-horror novel, that Great God Pan (published in installments in 1890, then expanded in '94) of which the critics of the last decades have spoken at length, making it emerge from the abyss of oblivion in which the literary critics of the late nineteenth century had rashly placed it for a long time, judging it a novel immoral and excessive.

Already elsewhere we have analyzed Machen's novel in question as well as the importance that the terrible archetype of the archaic god Pan covered England at the turn of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, between the advent of the second industrial revolution and the outbreak of the first world war (see M. Maculotti, Arthur Machen, prophet of the advent of the Great God Pan, in AaV.v., Arthur Machen: the sorcerer's apprentice, Bietti, Milan 2020). However, we had not mentioned, among the stories and novels of the time dedicated to the terrifying goat-footed god this novel by Jepson, which in hindsight should have entered by right, alongside The Touch of Pan di A. Blackwood, The Music on the Hill by Saki e Story of a Panic by EM Forster. Against the Bread of Machen, The Garden at 19pm is indebted to the point of being able to appear almost like a sequel to the first, enriched by a sort of "cameo" by the Welsh writer in the role of the character named Ambrose Marks, in which Jepson wanted to sympathetically portray his friend, even before the Master.

Jepson had previously paid homage to the god Pan: the novel published in 1904, six years before the one in analysis here had the title The Horned Shepherd, namely «the Horned Shepherd»… A clear reference to the Machenian divinity par excellence, who haunted the whole of British literature from the Victorian period on like a never satiated specter. That was the moment when the ancient benevolent and pastoral divinity that the Romantic poets and the Pre-Raphaelites raised to imago of the blissful existence of the golden Arcadia changed within a generation or two into something very different, so to speak in its dark doppelganger, in its shadow which for millennia had been, in the words of Hillman, removed. It is precisely from the abysses of the psychic repressed of Victorian bourgeois society that the goat-footed god, once again accessible to the psyche of the new writers across the Channel centuries after the abject testimonies of the nocturnal sabbaths and the witch hunt.

As always when I went to see him, on seeing us he said, with a thick, stammering voice, and laughing his hollow laughter: "Pan is not dead." The alienist spent nearly an hour with him, observing him, studying him, trying to make him talk. He only said twice: "Pan is not dead."

(chap. XXIV)

As he writes Bernardo Cicchetti, curator of the work [Cicchetti was also curator of Cheetah, published by Dagon Press last year with our appendix on Fatal and feral females in fantastic literature], in his preface, already in The Horned Shepherd Jepson gave his readers «forays into the world of pagan esotericism, where the theme of the presence of the gods of former religions and of their circulation in our world in disguise, with the consequent revival of neoclassical rites and impulses, had never ceased to fascinate and ensnare entire groups of artists of the word, music and figurative arts ». All this is obviously to be seen in connection with the flourishing of occult societies and esoteric circles, such as the famous Golden Dawn which included, among others, lovers of Celtic folklore as the same Do e WB Yeats, in addition to other writers such as the aforementioned Blackwood, Rohmer and Stoker, as well as "magic operators" of the caliber of Dion Fortune e Aleister Crowley. Crowley himself was able to read The Garden at 19pm on its release, in 1910, and he liked it so much that he recommended it to his followers as a compulsory reading to develop a realistic and modern vision of witchcraft and the cults of Old Religion Nowadays.

If in the Machenian inspirational novel the celebrations of forbidden rituals are left entirely to the reader's imagination, providing him with only and uniquely a philosophical and esoteric insight into the terrible power of the god Pan in action and some rare mention of the physical consequences of his work in our reality, the Jepson's pseudo-sequel it differs from the first one precisely by virtue of the fact that the hints to the rituals officiated by the participants of the villa at 19 Walden Road are repeated throughout the narration, with very precise indications of an astrological nature and non-trivial hints to type evocative practices goetic. If Machen's knowledge in the occult field was invaluable - having among other things cataloged thousands of hard-to-find titles, in the basement of a well-stocked esoteric bookshop, during his young London years - noteworthy must also have been those of Jepson, who it was not by chance that he caught a glimpse of Crowley himself. The latter, reading The Garden at 19pm in a London afternoon more than a century ago, perhaps he realized that sometimes tales and short stories can convey knowledge that is anything but illusions; as is also the case when reading Machen's most significant works and - perhaps even more so - by Gustav Meyrink.

Consider, among other things, the uncommon mention, in the first chapters, of the rhombus as a ceremonial object: a mention that presupposes a research by the author in the ethnographic field (e.g. the rites of the Australian aborigines or of certain North American tribes) and in that of the history of classical religions (the rhombus was one of the mystery tools par excellence in rituals Orphic, and in the myth also figured as one of the "toys" with which the Titans would have deceived Dionysus as a child to capture and dismember him). In the sixth chapter, in addition to the name of Pan, that of Nodens, the "god of the abyss" already mentioned by Machen in connection with the forbidden rites officiated by the Roman legion stationed at Carleon on Usk, in his Wales: a tremendous god who seems to be a full-blown double of Pan. The awakening of the goat-footed god, the main yearning of the sect that acts in the novel of Jepson, not casually passes through the infamous "Ritual of the Abyss", which includes grueling dances in front of a "terribly alive" statue of the god which is defined as "fascinating" although "terrible", a dichotomous yet not oxymoronic pair of adjectives taken on a par from the Machenian work of reference.

Hooves, hairy legs and heels identified her as a statue of Pan. […] My eyes fell on the face of the statue; and I shivered. The sculptor, a great artist, had set out to carve the face of the Pan of panic terror, of the Pan that drove those who saw it mad with fear; and he hadn't failed. An unspeakable, malignant pride shone in a plausible way from the sculpted features. Even in the cold stone it was awful beyond words.

The more I reflected on this new fact that I had learned - that there was a statue of Pan under the dome - the more I marveled. Pan did not seem to me the right god to occupy the main place in the ritual of the Abyss. Because, although the first conception of the devil was probably taken from Pan, I could not think that Woodfell and his friends would be influenced by it. I wondered if I shouldn't change my view of the creatures of the Abyss invoked in the rites. Marks had dropped a sentence about the forces of nature. Were these creatures of the Abyss gods of nature and not demons? Yet, among them was Moloch - I had heard him invoked - and surely Moloch was a devil. I was perplexed.

(chap. XXI, IX)

In fact, in addition to Pan and Nodens (his "double" of the "Romanized" Celtic area), other deities are also invoked in the Abyss ritual which is spoken of several times in Jepson's novel: seven in all, like the number of planetary heavens and initiations within the Mithraic Mysteries. In fact, to the rites of Pan and Nodens are added, among others, those of Adonis (thanks to a manuscript found in 1902 in a Tibetan monastery), Shiva e Moloch, the latter terrifying god at whose fiery altar the Canaanites sacrificed their firstborn with abject Carcosa unveiled, Postal Code. I): it is therefore no coincidence that, in the concluding chapter of Garden at 19, the narrator hypothesizes that, in particular at the Moloch ritual, Woodfell "had in mind for some years the human sacrifice instead of the sacrifice of the lamb". All this because Woodfell "he was not certain that there was more than one god of the Abyss, known to the nations and worshiped by them with many names; but he nevertheless he believed in the efficacy of approaching that power or powers through the various ancient paths"(Chap. XXIV).

Each of the rituals is celebrated in a different language and with their own gestures ("They must need a lot of instructions for those rites ... seven or eight foreign languagesAnd"; Postal Code. XX), and the entire ceremonial ends, as we have already mentioned, with the bloody sacrifice of a lamb. To these seven phases of the invocatory ritual, an octave is finally added, destined to definitively open the Abyss in the Walden Road # 19 Garden, which he sees as the protagonist Astaroth, demoness that the historians of religions indicate as the "heir" of the Sumerian-Babylonian Ishtar / Astarte, a deity on which Abraham Merritt centered on one of his best-known literary creations, recently reprinted in Italian by the types of Il Palindromo (Ishtar's ship.

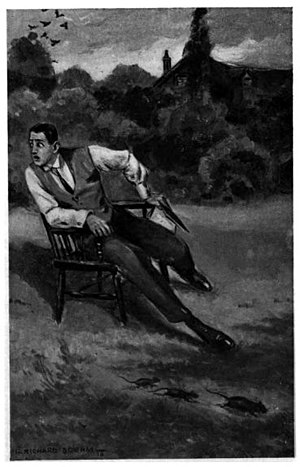

Particularly successful is the description, in the concluding chapters of the novel, of the "subtle" transformations that affect the entire Walden Road following the celebration of the Abyss rituals, a mutation felt by all the participants that naturally finds its center of gravity in the infamous garden of n.19 and that, nevertheless, mysteriously does not interest the house at n. 20 in which John Plowden lives, the narrator of the story; a subtle mutation of the territory that recalls that which HP Lovecraft he will describe in two of his most successful stories: The Color Out of Space (1927) and The Shunned House (1924):

Then the oppression of horror invaded the street itself. At night the menacing silence, deepened, always settled upon it, except when a strong wind blew, and the rustle and creak of the trees in the large garden across the street broke it. […] When I arrived halfway after dark, oppression fell upon me. I felt that I was approaching a horrible and evil presence.

I began to observe the garden of n. 19 at night after Pamela had re-entered it along the eaves. No wonder, with my nerves so tense, it seemed filled with strange sounds, creatures whispering and whispering among themselves under the sycamores. One night I could have sworn I heard a giggle - the only word to describe it is giggle - at the bottom of the garden. As I watched, my conviction grew that the dome was the true center of the expanding horror, that beneath it was the mouth of the Abyss.

(chap. XIII, XIX)

The mention of the terrifying Face evoked by Woodfell to punish one of the participants in the rituals, guilty of too rash advances towards his niece Pamela, instead anticipates The Green Face of the aforementioned Meyrink, published by the Austrian writer six years later of the novel under analysis here (1916):

Face it, Woodfell! Save me from the face! Take her away! […] Take her away! Take her away! Take her away! Face it, Woodfell! The face! The face! Take her away! I give you a thousand pounds to take her away! The face! Woodfell! A thousand pounds! The face! A thousand pounds! A thousand pounds! The face! Mil ...

There was one thing that somehow weighed on my mind: the statue of Pan. I had the feeling that it was a hub of evil influences. I had no doubt that it had been; and I couldn't free my mind from the fantasy that it still was. Sometimes his evil face entered my dreams.

(chap. XVI, XXIV)

La fatal woman archetypal which in the Pan of Machen was obviously represented by the infamous Helen Vaughan, terrible offspring of the goat-footed god, finds a counterpart in the novel by Jepson in the character of the homonymous Helen Ranger, chosen by Mr. Woodfell to fill the role of priestess of Astaroth in the concluding phase of the infamous Abyss ritual. Paradigmatic features such as (in primis) the tawny hair makes it an ideal "mask" of the Scarlet Woman of crowleyana memory. For her part, however, Woodfell embodies the archetype of the "frontier researcher / alchemist / occult operator", counterpart of the "mad scientist" in that Bread Machen makes possible the incarnation of the ancient demon-god through ultramodern experiments on the human brain. The operative apparatus ("In the room that he had used as a study was a collection of witchcraft tools, many of which, no doubt, recovered from his travels: an astrolabe, crystal balls, rotating rhombuses of different shapes, amulets, the entire set of one. Congo sorcerer and an Amerindian shaman"; Postal Code. XXIII) and bibliographic that distinguishes him rightfully places him in the vast list of similar characters in fantastic and supernatural literature at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Among the many we can remember the innumerable Herbert West (Herbert west, reanimator), Wilbur Whateley (Dunwich Horror), Robert Suydam (Horror at Red Hook), Crawford Tillinghast (FromBeyond) and dr. Munoz (cool air) Lovecraftian and other analogues born from the pen of Victorian and Edwardian authors of the caliber of Montagu Rhodes James e Arthur Christopher Benson. His diaries are full "of facts that cheer the heart of the ethnologist and folklore scholar»And record«his wanderings to the ends of the world, in search of the key to the mystery in primitive peoples, in primitive magic and in the simple minds of wild peoples"(Chap. XXIII).

As in the case of Machen, his friend and colleague Edgar Jepson's interest in the remote and smoky origins of religious practices in the (prei) history of humanity: a peculiarity that distinguished various English writers and scholars of the nineteenth century, among which we can mention the name of that Richard Payne Knight - also quoted by Machen (The Red Hand) - which witnessed the cultural survival, in modern times in Southern Italy, of ancient cults of fertility and fecundity exemplified iconographically by peculiar amulets anatomist in honor of the god Priapus. And, in this regard, it is finally highly significant that Jepson himself, in the concluding chapter of Garden of n.19, you speak explicitly of a case of "Panic possession" took place in the most important city in Southern Italy, enriching it with observations that recall typical situations of Fairy-Faith Gaelic (wandering on the "fairy" hills, having suffered a sudden and indecipherable shock) so dear to Machen (White People, Novel of the Black Seal, Shining Pyramid):

It is curious that his only words are: "Pan is not dead"; because there is a farmer in an asylum in Naples who says exactly those words. He was brought from the hills, where he had wandered for eighteen months; and the authorities have never been able to find out which village he belonged to, or what shock had destroyed his mind.

(chap. XXIV)