Tag: Cernunnus

The diabolical conferences of Arthur Christopher Benson

Dagon Press recently published in Italian - with the title "The closed window" (translation by Bernardo Cicchetti) - the supernatural tales of Arthur Christopher Benson, along with Montague Rhodes James one of the most significant "ghost-writers" English of the early twentieth century, as well as comparable in suggestions and themes to writers roughly contemporary to him and equally "esoteric" such as Arthur Machen, HP Lovecraft and Algernon Blackwood.

In the dark meanders of Carcosa

Il new essay by Marco Maculotti, published by Mimesis, allows you to cross the threshold of the lost city, to orient yourself among the symbols and references hidden behind the first season of “True Detective”.

Kernunnos: or of the perennial renewal of the cosmos

Primordial epiphany of the giver of life and death, archetypically connected to the dark forces of the natural world, the Celtic Cernunno was not only god of hunting and wild nature, but a real "cosmic god" ruler of the cycle of death-and - rebirth, as evidenced by the symbols attributed to it by traditional iconography: the stage with cervine horns, the torques and the horned snake.

The magic of the Mainarde: on the trail of the Janare and the Deer Man

A visit to Castelnuovo al Volturno, in Molise, allows us to give a face to the characters of local folklore, the Janare and "Gl'Cierv", and to resume some central mythical-traditional aspects of Cosmic-agrarian cults of ancient Eurasia.

The "Ghost Riders", the "Chasse-Galerie" and the myth of the Wild Hunt

(image: Henri Lievens, "Wild Hunt")

«Un old cowboy went out on horseback on a dreary windy day / rested on a ridge as he went for his road». Thus begins one of the most beautiful and famous country songs of all time: (Ghost) Riders in the Sky: A Cowboy Legend.

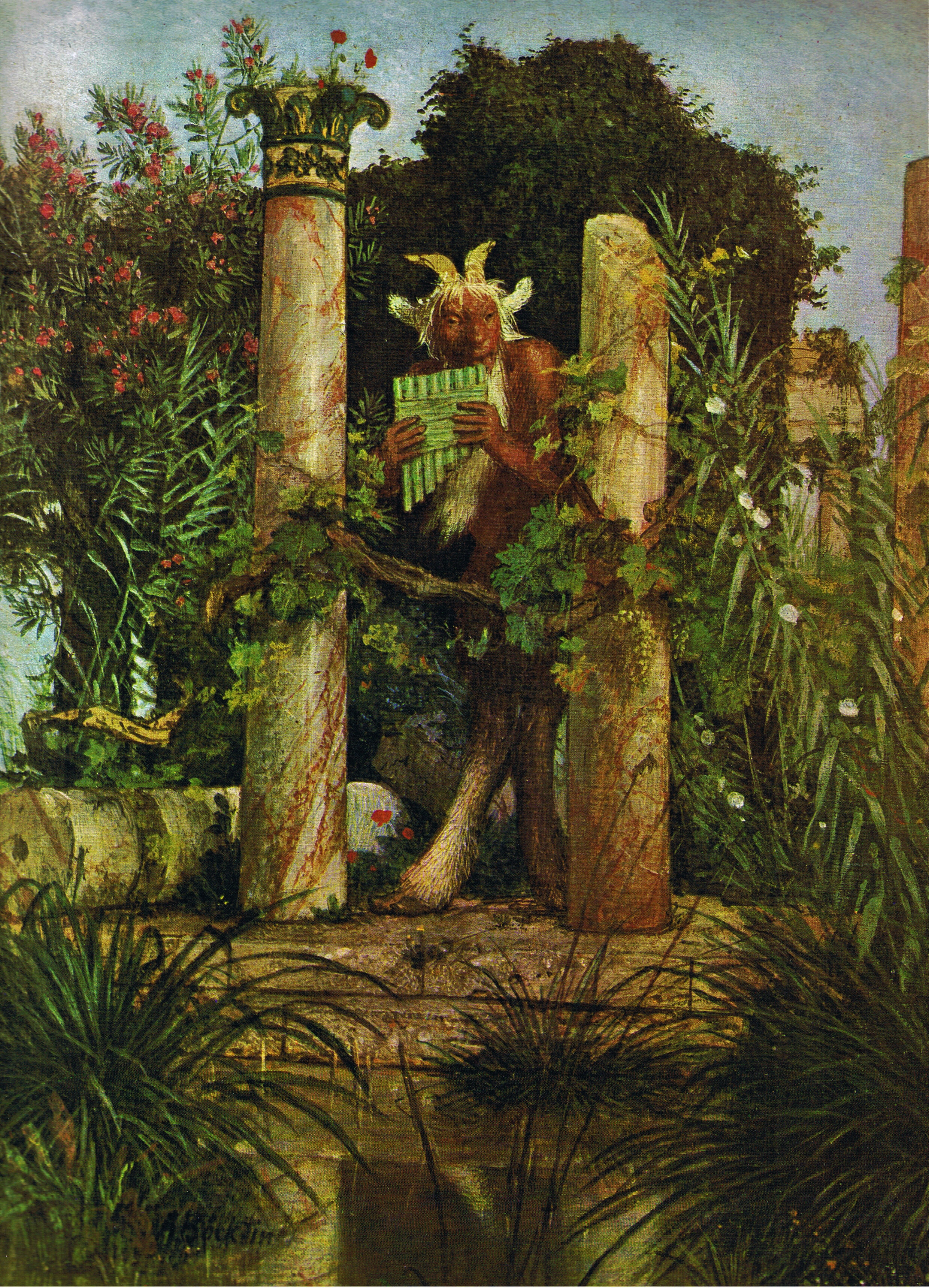

From Pan to the Devil: the 'demonization' and the removal of ancient European cults

di Marco Maculotti

cover: Arnold Böcklin, “Pan, the Syrinx-Blowing”, 1827

We have previously had the opportunity to see that, in the first centuries of our era and even during the medieval era, the cd. "Rural paganism" it kept its diffusion unchanged, especially in the areas further away from the large inhabited centers. St. Maximus noted that "in the fourth century (...) the first missionaries passed from city to city and rapidly spread the Gospel over a very large area, but they did not even touch the surrounding countryside", Then adding that" even in the fifth and sixth centuries, when most of them had long since been converted, in Gaul and Spain the Church, as shown by the repeated canons of the councils of the time, encountered great difficulty in suppressing the ancient rites with which peasants from time immemorial averted plagues e they increased the fertility of the flocks and fields"[AA Barb, cit. in Centini, p.101].

Cernunno, Odin, Dionysus and other deities of the 'Winter Sun'

di Marco Maculotti

cover: Hermann Hendrich, "Wotan", 1913

[follows from: Cosmic cycles and time regeneration: immolation rites of the 'King of the Old Year'].

In the previous publication we had the opportunity to analyze the ritual complex, recognizable everywhere among the ancient Indo-European populations, centered on theimmolation (real or symbolic) of the "King of the Old Year" (eg. Roman Saturnalia), as a symbolic representation of the "Dying Year" that must be sacrificed to ensure that the Cosmos (= the order of things), reinvigorated by this ceremonial action, grants the regeneration of Time and of the 'World' (in the Pythagorean meaning of Kosmos like interconnected unit) in the new year to come; year which, in this sense, becomes a micro-representation of the Aeon and, therefore, of the entire cyclical nature of the Cosmos. Let's now proceed toanalysis of some divinities intimately connected with the "solstitial crisis", to the point of rising to mythical representatives of the "Winter Sun" and, in full, of the "King of the Waning Year": Cernunno, the 'horned god' par excellence, as far as the Celtic area is concerned; Odin and the 'wild hunt' for the Scandinavian one and Dionysus for the Mediterranean area.

The Friulian benandanti and the ancient European fertility cults

di Marco Maculotti

cover: Luis Ricardo Falero, “Witches going to their Sabbath", 1878).

Carlo Ginzburg (born 1939), a renowned scholar of religious folklore and medieval popular beliefs, published in 1966 as his first work The Benandanti, a research on the Friulian peasant society of the sixteenth century. The author, thanks to a remarkable work on a conspicuous documentary material relating to the trials of the courts of the Inquisition, reconstructed the complex system of beliefs widespread up to a relatively recent era in the peasant world of northern Italy and other countries, of Germanic area, Central Europe.

According to Ginzburg, the beliefs concerning the company of the benandanti and their ritual battles against witches and sorcerers on the Thursday nights of the four tempora (Her hand, imbol, Beltain, Lughnasad), were to be interpreted as a natural evolution, which took place far from the city centers and from the influence of the various Christian Churches, of an ancient agrarian cult with shamanic characteristics, widespread throughout Europe since the Archaic age, before the spread of the Jewish religion - Christian. Ginzburg's analysis of the interpretation proposed at the time by the inquisitors is also of considerable interest, who, often displaced by what they heard during interrogation by the benandanti defendants, mostly limited themselves to equating the complex experience of the latter with the nefarious practices of witchcraft. Although with the passing of the centuries the tales of the benandanti became more and more similar to those concerning the witchcraft sabbath, the author noted that this concordance was not absolute:

"If, in fact, the witches and sorcerers who meet on Thursday night to give themselves to" jumps "," fun "," weddings "and banquets, immediately evoke the image of the sabb - that sabb that the demonologists had meticulously described and codified, and the inquisitors persecuted at least since the mid-400th century - nonetheless exist, among the gatherings described by benandanti and the traditional, vulgate image of the diabolical sabbath, evident differences. In these cEverywhere, apparently, homage is not paid to the devil (in whose presence, indeed, there is no mention of it), faith is not abjured, the cross is not trampled, there is no reproach of the sacraments. At the center of them is a dark ritual: witches and sorcerers armed with sorghum reeds who juggle and fight with benandanti provided with fennel branches. Who are these benandanti? On the one hand, they claim to oppose witches and sorcerers, to hinder their evil designs, to heal the victims of their hexes; on the other hand, not unlike their presumed adversaries, they claim to go to mysterious nocturnal gatherings, of which they cannot speak under pain of being beaten, riding hares, cats and other animals. "

—Carlo Ginzburg, "I benandanti. Witchcraft and agrarian cults between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries», Pp. 7-8