Let's take a closer look at the famous essay Zen and archery by philosopher Eugen Herrigel connecting it to Yukio Mishima's philosophy of life and the samurai code. An art without art, a continuous metamorphosis, the action in its original purity.

di Lorenzo Pennacchi

«One stroke – one life!», this is how the Japanese bow masters summarize their discipline, understood as an art. A ritual art with a profound value in itself, but also preparatory for assimilating the essence of Zen. It is in this perspective that Eugen Herrigel, professor of philosophy at Tōhoku Imperial University in Sendai, undertook an internship of kyudo (“via dell'arco”) from 1924 to 1929. Under the watchful guidance of the master Awa Kenzo, the Western philosopher came into contact with traditional Japanese wisdom, seeking answers along a path that marked the overturning of common sense and the change of one's self. The experience is retraced in the short book Zen and archery, published in 1948. The first pages revolve around the ancestral attraction for mystique, conceptually impenetrable, related to a series of awarenesses, considerations, perplexities:

I had therefore recognized that there is and can be no other way to mysticism than that of one's own experience and suffering and that without this premise all that can be said about it is nothing but empty words. But – how does one become a mystic? How do you reach the state of detachment, the real one, not the imaginary one? Is there still a way that leads there, even for one whom the abyss of centuries separates from great masters? For modern man, who grows up in completely different conditions?

[1]

It is with these premises that the philosopher embarks on the path, aware of the historical and cultural differences that characterize it. The archery Japanese is not only an art of war nor even less a sporting discipline, but a spiritual practice which first of all foresees aintense struggle with yourself. Fight against your ego, reject rationalization, focus on breathing. Inhalation and exhalation as two moments of a single circular process, in which to conquer harmony to free the mind and strike the blow. In Spiritual lessons for young samurai (1968-1969) Yukio Mishima confirms its importance, extending it to life:

I believe that it is necessary to rediscover what appears to be fundamental in the life of a man, a continuous spiritual tension in the course of daily events, the typical tension of one who knows how to wait with vigilant spirit for the moment of danger. [...] He has the need to strenuously and incessantly stretch his body and his life like a bow.

[2]

After all, the very notion of street is central to the traditional Japanese imagination. In an etymological sense everything is away: bushidō ("way of the warrior"), budo (“martial way”), kyudo as anticipated. In the hagakure, the secret code of samurai composed by the master Yamamoto Tsunetomo and by the pupil Tashiro Tsuramoto at the beginning of the eighteenth century, but published only in 1906, we find a significant definition:

Indeed, the Way is nothing more than knowing one's faults. The Way is to always examine your own conduct and try to correct yourself. The word "wise" is made up of two ideograms meaning "to know" and "defect".

[3]

It is precisely in this horizon of meaning that Herrigel's apprenticeship unfolds. Initially linked to Western, individualistic and rationalizing styles, the philosopher has slowly turned towards a new model of awareness, fueled by the repetition of gestures and by detachment from oneself. The perfect shot, where there is no longer any difference between the man and the bow, is not shot by the archer, but “Yes” he pulls. The one handed down by the master Kenzo is a practice that necessarily provides for the interpenetration between the objective and the subjective, the abandonment of one's ego, the disposition to aim, aim and hit not so much an external target as one's own soul, being pierced from side to side. In this sense the spirit reveals itself, is exposed, merges with the action and then learns the great doctrine:

Art becomes artless, shooting a non-shooting, shooting without a bow or arrow; the teacher becomes a pupil again, the end a beginning and the beginning a completion.

[4]

In the final part of the book, Herrigel draws a parallel with swordsmanship. Here too, as reported by the great master takuan, detachment from oneself, from one's sword and from the opponent are the conditions for the perfect blow. It's right since absolute void, in fact, that "the action blossoms marvelously" [5]. nell 'Introduction to the philosophy of action (1969-1970) Mishima highlights some characteristics of the actions. The speed that leaves no room for reflection, unless before or after it has been completed, the model, the planning, but above all the beauty:

The action is entirely subjective. The action is equivalent to a force that rushes upon a target forming a geometric place, and can be as beautiful as the running of a deer, which however is absolutely unaware of its own grace.

[6]

The action cannot be disturbed by external interventions or compromises because it requires tension and tragedy. It is an individual act, in which the individual defeats himself, focusing solely on thepresent moment. Not on the bow nor on the arrow, but on breathing. And then the practice, repeated and internalized, becomes art, the art of life. As Tsunetomo testifies:

The most important thing in life is to live the present moment with the utmost attention. All existence is nothing but a succession of one moment after another. If you understand this, there is no more need to go from one place to another and look elsewhere.

[7]

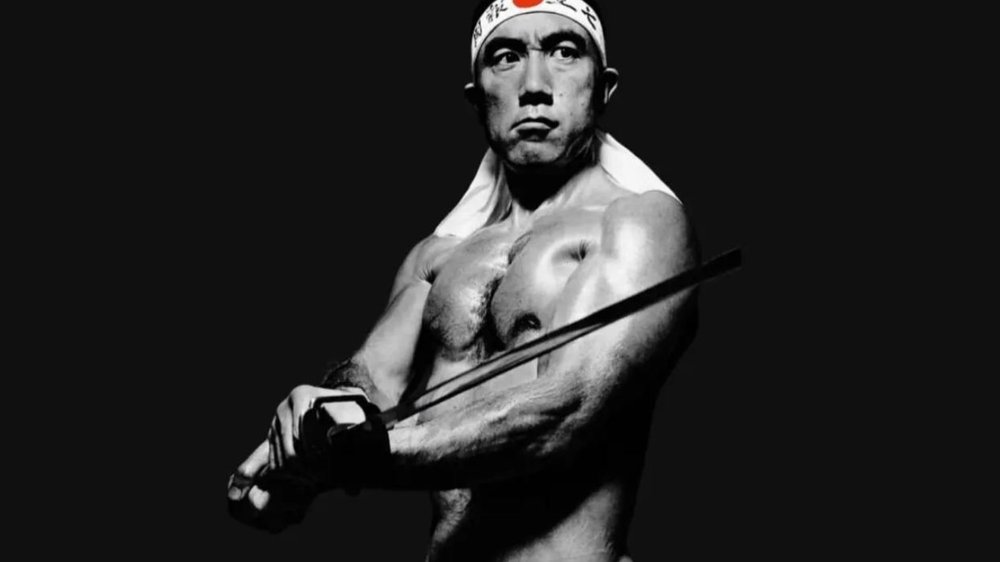

For Mishima the practice of the way, in his case of kendo, is a way to escape from the quagmire of nihilism. Arrived at this awareness as an adult, for him action has the power to heal the spirit from the disease of literature, which afflicted him so much in his youth. These are considerations to be contextualised, of course. But they contain within them a sense of instinctive, ancestral, universal truth. Even because Mishima is the emblem of action, in total contrast with the contemporary world: the man who preferred the seppuku to compromise. Death as an integral part of life, as its maximum attestation, as a true samurai.

Yet the action is manifest in many ways. What master Kenzo passed on to Herrigel, and which he shared with us, is one pure manifestationfree from external motivations. It is an artless art of a man who continually defeats himself to rediscover himself stronger. A cycle of perennial metamorphoses, in which the teacher is always a pupil, through which "he will encounter the truth no longer reflected, the truth above all truths, the formless origin of all origins: Nothingness, which is also everything - will be swallowed up and will be reborn From it" [8].

NOTE:

[1] E. Herrigel, Zen and archery, Adelphi, Milan 1973, p. 30.

[2] Y. Mishima, Spiritual lessons for young samurai, in Spiritual lessons for young samurai, Universal Economic Feltrinelli, Milan 2011, p. 19.

[3] Y. Tsunetomo, Hagakure. The secret code of the samurai, Einaudi, Turin 2010, p. 28.

[4] Herrigel, p. 22.

[5] Ibid, p. 94.

[6] Mishima, Introduction to the philosophy of actionin spiritual lessons, p. 93.

[7] Tsunetomo, p. 79.

[8] Herrigel, p. 99.